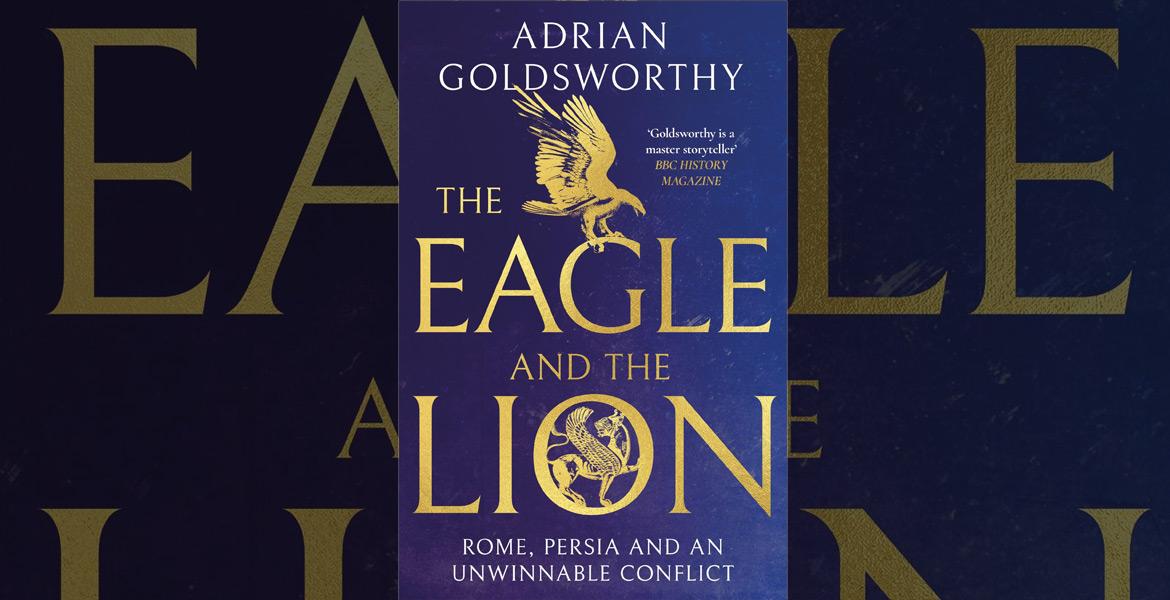

The Eagle and the Lion, Adrian Goldsworthy

In The Eagle and the Lion Adrian Goldsworthy has set out to achieve the almost impossible: to provide a complete history of the relationship between Rome and ParthianAn empire that at its height stretched from what is now Turkey to Pakistan, which was ruled by the Arsacid kings. It lasted from 247 BCE to 224 CE.-SasanianAn ancient empire, lasting from 224 to 651 CE, that at its peak stretched from modern Turkey and Egypt to Pakistan. empires across seven centuries, from the first contact between Sulla and Orobazus in the 90s BCE'Before common era', the non-religious way of saying 'BC' (which means 'before Christ'). until the fall of the Sasanian, and the great reduction of the Roman, empires during the Arab conquests in the seventh century. This is no mean feat. For while most might be aware of a few significant moments – the Battle of Carrhae, for example, or the capture of the emperor Valerian – so much more happened that is little known, little understood, and little sourced.

This is the beauty of The Eagle and the Lion. In casting his net across the full period of contact, Goldsworthy has shown that our perceptions are distorted. Absolutely, these were two massive, aggressive empires, dominating huge swathes of territory and commanding significant numbers of subjects and allies. At their peaks, the two empires controlled the land from what is now Pakistan to Britain, with tentacles reaching far beyond. This level of power was not achieved through being 'nice'. Yet for much of their combined existence, Rome and PersiaThe ancient area of land that at its peak stretched from parts of North Africa to parts of India, ruled by the Achaemenid (550-330 BCE), the Parthian (247 BCE - 224 CE), and the Sasanian (224-651 CE) dynasties. lived in something approaching peace – with sabres. Limited wars with limited outcomes were sometimes fought – or negotiated around – in the frontier zones, but usually the empires were too well balanced for one to achieve total annihilation of the other. This is not to say there was no struggle for dominance, but there are many ways to skin a cat, and posturing and propagandaBiased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view. could be as effective as significant bloodshed in achieving the desired outcomes. Only when there were perceptions of extreme weakness, or massive destabilization, might goals change.

There is, obviously, the potential for a parallel to be drawn here. With war in Ukraine, often painted as an all-out battle between East and West, in the forefront of the public's mind and the ongoing colder global 'conflict' between the two hemispheres providing perhaps a more permanent backdrop, there is much to contemplate. Goldsworthy's point, amidst complaints about the public tending to look no further than Nazi Germany for similarities, is that it is possible for strong empires to live successfully, if not necessarily happily, side by side. It might even have gone further. As he says, ‘While it is hard to prove that the rivalry benefitted both empires and contributed to their success and longevity, it certainly does not appear to have been a major source of weakness.’ P. 520. Weakness for the Romans and Sasanians instead came from upsetting that fine balance in pursuing something more akin to a total war, in seeking to obliterate on the one hand and defend against an existential threat on the other. Across the book, Goldsworthy is illustrating the simple point that not all lessons from history have to be drawn from the first half of the twentieth century. This argument certainly holds up for the current global situation; whether it is equally as strong for the more localized issue remains to be seen.

P. 520. Weakness for the Romans and Sasanians instead came from upsetting that fine balance in pursuing something more akin to a total war, in seeking to obliterate on the one hand and defend against an existential threat on the other. Across the book, Goldsworthy is illustrating the simple point that not all lessons from history have to be drawn from the first half of the twentieth century. This argument certainly holds up for the current global situation; whether it is equally as strong for the more localized issue remains to be seen.

The fact that the argument is not so convincing when applied to Ukraine is, perhaps, a symptom of the type of book Goldsworthy has written. The longue duréeA style of studying history, which focuses on long-term historical structures and changes - including societal and environmental - rather than on individual historical moments and events. approach provides a fascinating insight into the lifespans of ideas, cultures, and empires, but it is not revealing when we want to consider independently specific events, movements, or people. It is the weather forecast of the history world: it's great at stating whether somewhere in a rather large geographic area is going to have rain, but it doesn't tell me if I need an umbrella to walk to the shop. So we see how the two empires interacted with each other over centuries: we learn to spot the signals that tell us some sort of fighting will break out or when the empires will tire and sue for peace; we see the movement of the border like the tide waxing and waning on the sand, the current pulling individual cities this way and that. But, with a few notable exceptions, it is not possible for a moment to come alive any more than it is possible to command the sea to retreat.

Goldsworthy is aware of the problems of his approach, just as he is aware of the problems of the sources, which – where they exist at all – tend to be Greco-RomanOf, or influenced by, ancient Greece and Rome.. And just as he has taken steps to overcome the bias in the sources, using additional, non-documentary material to ensure the Parthian-Sasanian point of view receives due attention, he has also worked hard to overcome the inherent issues with covering so much history in so little space. The narrativeA story; in the writing of history it usually describes an approach that favours story over analysis. is strong, characters stand out, and certain events are covered in gripping detail. There is pace, and there is colour. There is also considered and consistent challenge to many prevailing assumptions, proven with sound logic and the ability to draw on seven centuries of examples. In doing so, Goldsworthy has managed to marry two disparate methods of writing history. In going broader he has added depth to our understanding, not just about the Romans and the Parthian-Sasanians, but about how all empires live and die – and how they can co-exist together.

- Log in to post comments