A Brief History of History

Key facts about history

- Our idea of history has changed over time, and has been influenced by many things.

- The word 'history' comes from the Ancient Greek word for 'inquiry'.

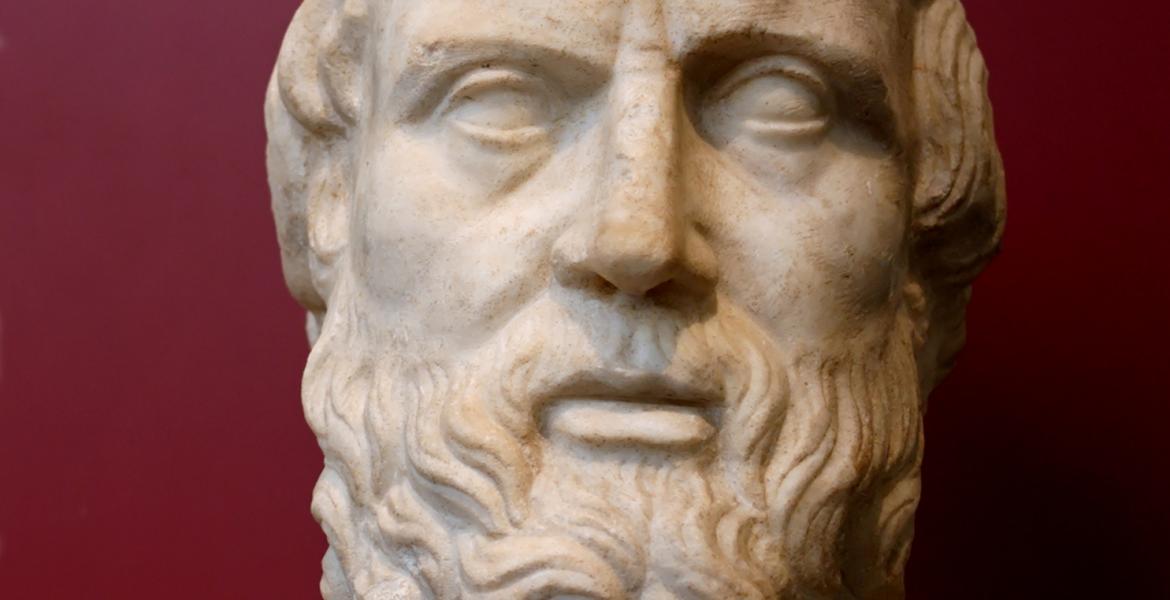

- Herodotus is considered as the father of history

- Today, there are many different ways people approach and understand history

People you need to know

- Johannes Guttenberg - credited with introducing the printing press to Europe.

- Herodotus - Ancient Greek historian, considered the father of history, who lived in the fifth century BCE'Before common era', the non-religious way of saying 'BC' (which means 'before Christ').'Before common era', the non-religious way of saying 'BC' (which means 'before Christ')..

In the ancient past, what we would call ‘history’ was something created and recreated to fit a purpose: a king might invent a history of himself and his family to explain why he took the throne, or a myth might be made to explain a brutal war. Facts, or what actually happened, didn’t matter as much as the story. The past, when told like this, moved: stories changed over time to suit those telling them. Almost 2,500 years ago a Greek from Halicarnassus (Bodrum in Turkey) named Herodotus set out to change this. He was born towards the end of the Persian Wars, in which the Greeks fought the Persians (who were based in modern-day Iran, but whose empire stretched from the Aegean Sea in the west to parts of China in the east) in the great battles of Marathon, Thermopylae (where the Spartan 300 stood), and Salamis. He wanted to record the events that had happened and find out what had caused them, and so travelled around, finding information in records and talking to people. As Herodotus said in his Histories ‘The purpose is to prevent the traces of human events from being erased by time, and to preserve the fame of the important and remarkable achievements produced by both Greeks and non-Greeks; among the matters covered is, in particular, the cause of the hostilities between Greeks and non-Greeks.’ The Histories, Robin Waterfield translation (2008) He called his work his ‘Inquiry’. In Ancient Greek, the word was ‘Historia’.

As Herodotus said in his Histories ‘The purpose is to prevent the traces of human events from being erased by time, and to preserve the fame of the important and remarkable achievements produced by both Greeks and non-Greeks; among the matters covered is, in particular, the cause of the hostilities between Greeks and non-Greeks.’ The Histories, Robin Waterfield translation (2008) He called his work his ‘Inquiry’. In Ancient Greek, the word was ‘Historia’. The more specific translation of ‘historia’ is choosing wisely between conflicting accounts Other people in the ancient world learned of his work and were inspired, and so the practice of history began. When the Romans came along, they adopted much of Greek learning,

The more specific translation of ‘historia’ is choosing wisely between conflicting accounts Other people in the ancient world learned of his work and were inspired, and so the practice of history began. When the Romans came along, they adopted much of Greek learning, Greek remained the language of the learned during the Roman period, and was the most common language spoken in Rome. The great universities of the time, our Oxbridge, were in Greece (at Rhodes and Athens) and those who fancied themselves either as academics or cultured (such as the Emperor Nero) would flock to Greece. However, Roman traditionalists, particularly in the Senate, did not find this philhellenism becoming, feeling it threatened their ideals of masculinity. Medicine also remained in Greek hands during the Roman Empire, which explains why most of our medical terminology comes from Greek. including history (the word for which they adopted into their Latin language, and it came to mean ‘a narrativeA story; in the writing of history it usually describes an approach that favours story over analysis.A story; in the writing of history it usually describes an approach that favours story over analysis. of past events’) and the practice spread further. Roman writers such as Cicero laid down rules for the writing of history. These included that the truth should be told impartially (regardless of who it might offend); should be organised chronologically and geographically; it should provide a narrative of great events, their causes and their protagonists; and that it should be well written. Once belief in Christianity took hold across Europe, learning and knowledge became more limited and was restricted to monks and others within the Church. As all books had to be written by hand, monks would spend days writing and copying texts.

Greek remained the language of the learned during the Roman period, and was the most common language spoken in Rome. The great universities of the time, our Oxbridge, were in Greece (at Rhodes and Athens) and those who fancied themselves either as academics or cultured (such as the Emperor Nero) would flock to Greece. However, Roman traditionalists, particularly in the Senate, did not find this philhellenism becoming, feeling it threatened their ideals of masculinity. Medicine also remained in Greek hands during the Roman Empire, which explains why most of our medical terminology comes from Greek. including history (the word for which they adopted into their Latin language, and it came to mean ‘a narrativeA story; in the writing of history it usually describes an approach that favours story over analysis.A story; in the writing of history it usually describes an approach that favours story over analysis. of past events’) and the practice spread further. Roman writers such as Cicero laid down rules for the writing of history. These included that the truth should be told impartially (regardless of who it might offend); should be organised chronologically and geographically; it should provide a narrative of great events, their causes and their protagonists; and that it should be well written. Once belief in Christianity took hold across Europe, learning and knowledge became more limited and was restricted to monks and others within the Church. As all books had to be written by hand, monks would spend days writing and copying texts. There’s a fabulous legend relating to the largest known surviving medieval manuscript in the world, the Codex Gigas. Thought to have been created in the 13th century, it contains the full Bible, plus a number of historic documents written in Latin. The myth goes that the monk who created it had broken his monastic vows, and as punishment was to be walled up alive. In bargaining for his life, he promised to pen in one night a book that would contain all of human knowledge and glorify the monastery forever. He was allowed to set about his task, but by midnight he was sure that he would fail, and would therefore suffer his punishment. To avoid it, he is said to have made a pact with the devil, who completed the manuscript for him, and put his signature (a picture of the devil) within it. The book has since been known as the Devil’s Bible. Tests have shown that it would have taken five years of solid writing to have completed it. This meant that the Church controlled the information, and decided what other people should know. History continued to be recorded and studied, but now it was within the limits of a Christian understanding of the world, and within the limits of Christian scripture, which was taken as truth.

There’s a fabulous legend relating to the largest known surviving medieval manuscript in the world, the Codex Gigas. Thought to have been created in the 13th century, it contains the full Bible, plus a number of historic documents written in Latin. The myth goes that the monk who created it had broken his monastic vows, and as punishment was to be walled up alive. In bargaining for his life, he promised to pen in one night a book that would contain all of human knowledge and glorify the monastery forever. He was allowed to set about his task, but by midnight he was sure that he would fail, and would therefore suffer his punishment. To avoid it, he is said to have made a pact with the devil, who completed the manuscript for him, and put his signature (a picture of the devil) within it. The book has since been known as the Devil’s Bible. Tests have shown that it would have taken five years of solid writing to have completed it. This meant that the Church controlled the information, and decided what other people should know. History continued to be recorded and studied, but now it was within the limits of a Christian understanding of the world, and within the limits of Christian scripture, which was taken as truth. Rich families might commission works of history, and would also have greater access to information. Western medieval knowledge expanded thanks to contact with the Arab world during the Crusades, and again as direct trade with the rest of the world increased. In 1440, Johannes Guttenberg introduced the printing press to Europe.

Rich families might commission works of history, and would also have greater access to information. Western medieval knowledge expanded thanks to contact with the Arab world during the Crusades, and again as direct trade with the rest of the world increased. In 1440, Johannes Guttenberg introduced the printing press to Europe. He’s usually credited with the invention of the printing press, although printing had been in use in Asia for at least 600 years before Europe got a press. Instead of relying on monks to copy books, more books could now be printed in less time. Reliance on the Church for information reduced and more information from a variety of sources became available. At the same time, interest in Classical Greece and Rome grew, and learned people looked to the ancient writers, such as Cicero, to inspire them.

He’s usually credited with the invention of the printing press, although printing had been in use in Asia for at least 600 years before Europe got a press. Instead of relying on monks to copy books, more books could now be printed in less time. Reliance on the Church for information reduced and more information from a variety of sources became available. At the same time, interest in Classical Greece and Rome grew, and learned people looked to the ancient writers, such as Cicero, to inspire them. This was partly due to the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, which caused a wave of Greek speaking intellectuals and Greek texts to spread into Europe. It was also around this time that the meaning of the word ‘history’ became what it is today: the study of the past through the written word. However, belief in the Bible as the truth was still strong, so people fit what they learned about the world and the past into the story told in the Bible.

This was partly due to the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, which caused a wave of Greek speaking intellectuals and Greek texts to spread into Europe. It was also around this time that the meaning of the word ‘history’ became what it is today: the study of the past through the written word. However, belief in the Bible as the truth was still strong, so people fit what they learned about the world and the past into the story told in the Bible. One good example of this is the Red Lady of Paviland. The Reverand William Buckland discovered a set of bones stained red with ochre buried in a cave on the Gower Peninsula. As a creationist, he believed that no human remains could be older than the Great Flood, and that the world itself was only born in 4004BC. Buckland therefore decided the bones belonged a woman of ill repute (hence the red staining) dating to the Roman period, who had been a follower of a Roman camp (which was actually an Iron AgeThe Iron Age of the British Isles covers the period from about 800BCE to the Roman invasion of 43CE, and follows on from the Bronze Age.The Iron Age of the British Isles covers the period from about 800BCE to the Roman invasion of 43CE, and follows on from the Bronze AgeThe Bronze Age was a time between the Neolithic and the Iron Age, which is characterised by the use of the alloy bronze. In Britain it lasted from about 2500BCE until about 800BCE.. fort). However, the Red Lady was in fact a man, possibly a shaman or someone of great importance, who lived around 33,000 years ago. This carried on until the 19th century when archaeological finds, such as dinosaurs and prehistoric humans, became too many to ignore. Scientific discoveries made the great minds of the day rethink their dependence on Christianity for understanding history, and began to look at history in new ways. One of these ways was to see it as a progression of events, a move from ‘bad’ to ‘good’ across the years. Others saw in history a time that was inspiring, to which they wanted to return. The stories told in history changed, as did their meaning, and that is the history we have been left with today.

One good example of this is the Red Lady of Paviland. The Reverand William Buckland discovered a set of bones stained red with ochre buried in a cave on the Gower Peninsula. As a creationist, he believed that no human remains could be older than the Great Flood, and that the world itself was only born in 4004BC. Buckland therefore decided the bones belonged a woman of ill repute (hence the red staining) dating to the Roman period, who had been a follower of a Roman camp (which was actually an Iron AgeThe Iron Age of the British Isles covers the period from about 800BCE to the Roman invasion of 43CE, and follows on from the Bronze Age.The Iron Age of the British Isles covers the period from about 800BCE to the Roman invasion of 43CE, and follows on from the Bronze AgeThe Bronze Age was a time between the Neolithic and the Iron Age, which is characterised by the use of the alloy bronze. In Britain it lasted from about 2500BCE until about 800BCE.. fort). However, the Red Lady was in fact a man, possibly a shaman or someone of great importance, who lived around 33,000 years ago. This carried on until the 19th century when archaeological finds, such as dinosaurs and prehistoric humans, became too many to ignore. Scientific discoveries made the great minds of the day rethink their dependence on Christianity for understanding history, and began to look at history in new ways. One of these ways was to see it as a progression of events, a move from ‘bad’ to ‘good’ across the years. Others saw in history a time that was inspiring, to which they wanted to return. The stories told in history changed, as did their meaning, and that is the history we have been left with today.

Things to think about

- How has history changed over the last 3,000 years?

- What is meant by history today?

- What does the way we study history tell us about ourselves?

- What does history mean to you?

Things to do

- Read some history books written at different times to see how people's approach to history has changed.

- Try writing a historical event from different perspectives in time.

- Log in to post comments