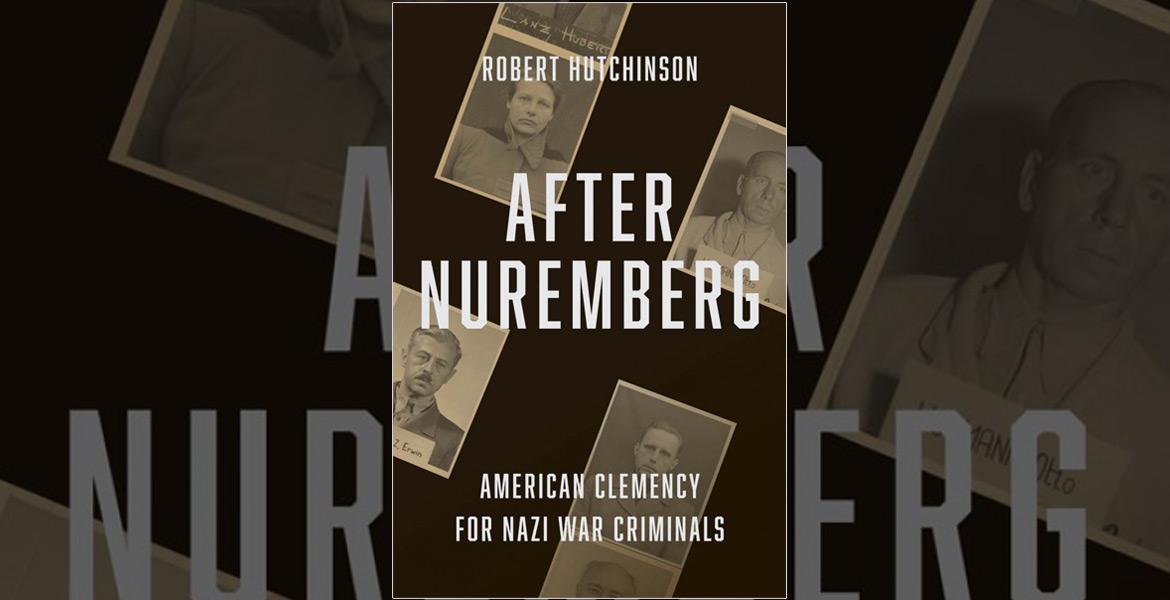

Robert Hutchinson, After Nuremberg

‘Of the 142 Germans convicted of war crimes at the twelve Nuremberg Military Tribunals from December 1946 to April 1949, eighty-eight men and one woman remained incarcerated at Landsberg in January 1951. Of these eighty-nine, seventy-seven received clemencyShowing forgiveness and mercy in the act of judging punishment., which included commutations of ten out of fifteen death sentences.’ P. 1.

P. 1.

It's an astounding statistic: that so any mass murderers, employers of slave labour, abusers, and tormentors were able to walk free, often within just ten years of their trial, requires explanation. Robert Hutchinson's After Nuremberg attempts to do just that. Using previously overlooked sources and recently declassified information, he brings new and piercing insight to this travesty of justice.

The standard excuse for this clemency has always been 'Cold WarA period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, 'officially' lasting from 1947 to 1991. expediency': the realpolitik of appeasing certain important sections of West Germany society to present a united front in fighting the 'real' enemy of the Soviet UnionThe Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) or Soviet Union, was a Marxist-Leninist state covering much of eastern Europe, Russia and Asia between 1922 and 1991.. Ironically, this use of a German bulwark against communismA theory of system of government and social organisation where property is owned collectively and each person contributes and receives according to their ability and needs. is not that dissimilar from the rationale behind the appeasement of Hitler between 1933 and 1939. Hutchinson, however, looks beyond this simple reason to the thoughts, both public and private, of those at the heart of the clemency proceedings to provide an entirely new interpretation of the American pursuit of 'justice' for the war criminals, and the result is surprising.

The road to hell, so the expression goes, is paved with good intentions. As with so much on either side of the Second World WarA global war that lasted from 1939 until 1945., it certainly also seems to be the case here. For High Commissioner John McCloy and his successors seemed, more than anything else, to be concerned with 'justice' - specifically showcasing their idea of 'American justice'. Thus, everything they did, every action they took, was directed by the idea of providing war criminals with the same rights of appeal and parole as offered to those held in American prisons. Yet here is another irony: the United States is not famed internationally for its fair access to justice - with one of the largest relative prison populations in the world, disproportionately of non-white people, the impression is not one of moderation, restraint and equality. But the war criminals were granted far more than their American counterparts: appeals without consultation of the full trial records or the judges and prosectors who secured their convictions; benefit of doubt that wasn't merely walking the tightrope of credulity, but dancing a tango with it; the constant downgrading of sentences based on the notion that mercy offered once should be freely given to the same individual again; and ignoring the thousand of lives destroyed because ten were spared on a whim. Perhaps the greatest irony of all was that in this pursuit of justice, the greatest injustice was done by calling into question the very processes and findings of Nuremberg.

The extent of clemency, and the disparity between the two systems, does cast a sliver of doubt on Hutchinson's argument that McCloy was primarily concerned with American justice rather than the Cold War. He obviously believed it, but the facts still speak towards more going on than perhaps he and his successors cared to admit, even to themselves. After all, this shining example of justice was set up as a direct contrast to Soviet notions of the same. The competition, even on an implicit level, points to the influence of the international situation in guiding decisions. Surely no-one can be that naïve otherwise.

Nevertheless, Hutchinson argues his case strongly, and with considerable passion. There is an exasperation with the High Commission for Occupied Germany that is absolutely deserved, and this transfers to the reader. Despite the razor-sharp, flowing and articulate prose, this therefore means that After Nuremberg is not the easiest book to read: the subject is simply too awful, too infuriating. Yet it is also an extremely important book, not just because it gives the reader a fuller understanding of what happened after Nuremberg, but because it is all too relevant today. With the International Criminal Court looking to press charges against crimes in Eastern Europe - and significant sections of the world refusing to acknowledge its legitimacy - it becomes a necessity to understand the roots of the theory and application of international law. But beyond that, After Nuremberg raises questions about justice that go right to the heart of the matter: are some crimes just too heinous, on too massive a scale, to be treated as 'ordinary', and consequently should those perpetrators be treated differently? What even is justice - is it more concerned with rehabilitation or with punishment? And justice for whom - the victims, the perpetrators, or both - and how can that ever be achieved? Societies will continue to grapple with these questions and, in all probability, continue to fail in finding solutions satisfactory to all.

- Log in to post comments