Dan Jones and Marina Amaral: In Conversation

Dan Jones is a medieval historian, with best-selling books on the Plantagenets, Magna Carta, and the Templars. He is also a broadcaster, having worked on numerous TV programmes including The Secrets of Great British Castles and Henry VIII and His Six Wives, as well as being an award-winning journalist who has written for newspapers and magazines in both the United Kingdom and the United States.

Marina Amaral is an internet sensation whose work on the colourisation of black and white photographs has taken the world by storm. With considerable research and skill, she has brought colour to her subjects, including the fascinating Napoleon’s Grande Armée Veterans series and the harrowing Faces of AuschwitzThe concentration and extermination camp, located in Poland, that has become synonymous with the Holocaust..

The two have now joined forces to create the remarkable, bestselling The Colour of Time, which tells the story of the world from 1850 until 1960 using newly-colourised photographs. They have just finished a whistle-stop tour of the United Kingdom, and we were lucky enough to catch up with them in Oxford to chat about their book.

How did the collaboration between the two of you begin?

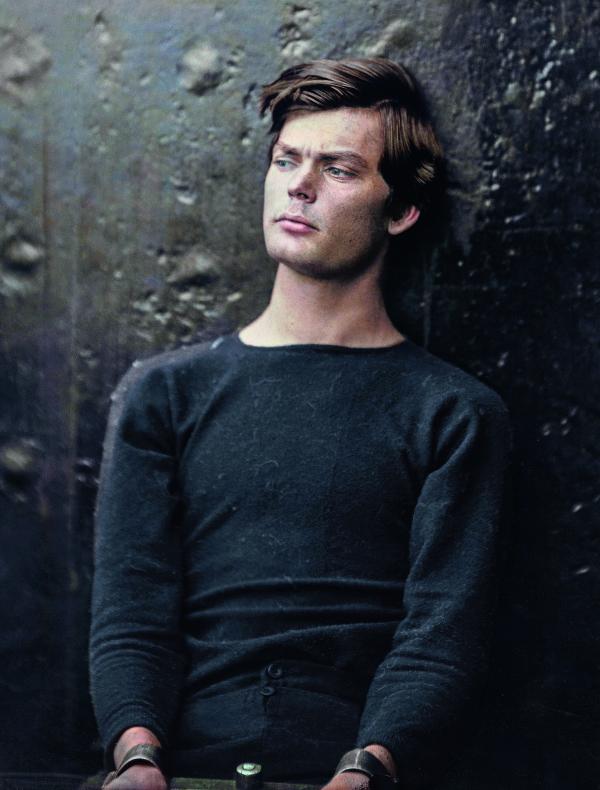

Marina: In 2015 I needed some images, but I didn't know anybody that could help me to create them, so I found some Photoshop tutorials on You Tube and taught myself. A few months later I saw a collection of colourised photos of the Second World WarA global war that lasted from 1939 until 1945.A global war that lasted from 1939 until 1945. A global war that lasted from 1939 until 1945. A global war that lasted from 1939 until 1945. . I decided I wanted to try to do this technique to create a similar effect with my own images. I had no idea of what I would need to do, but I chose a picture of an American Civil War soldier and I started playing around and trying to understand the Photoshop tools and the best way to approach the image. From there I started to develop my own technique and workflow and I got to a point where my work became viral on the internet, and then I posted a photo of a conspirator who was involved in the plot to assassinate Lincoln and that's how Dan found me.

Dan: I'd seen a lot of historians - academic historians, popular historians, my peers and people I respect - all suddenly going 'you've got to see this Lewis Powell picture' and retweeting it. And, like them, my mind was blown by the juxtaposition of someone from a very famous historical event, but looking so contemporarySomeone or something living or occurring at the same time.Someone or something living or occurring at the same time.Someone or something living or occurring at the same time.Someone or something living or occurring at the same time., fresh, in colour; and I thought ‘the work here is incredible’. So, I got in touch with Marina via Twitter and we started chatting and came up with the idea of collaborating on a book that would be a history from 1850 - about the time that photography becomes part of a historical record, which really was the Crimean WarA war fought between Russia, and Britain, France, Turkey and Sardinia from 1853 to 1856. It was concerned primarily with the expansion of Russia but it also had religious overtones.A war fought between Russia, and Britain, France, Turkey and Sardinia from 1853 to 1856. It was concerned primarily with the expansion of Russia but it also had religious overtones. A war fought between Russia, and Britain, France, Turkey and Sardinia from 1853 to 1856. It was concerned primarily with the expansion of Russia but it also had religious overtones. A war fought between Russia, and Britain, France, Turkey and Sardinia from 1853 to 1856. It was concerned primarily with the expansion of Russia but it also had religious overtones. - through to the Cold WarA period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, 'officially' lasting from 1947 to 1991. era when colour photography really became the rule and not the exception. So that was the very simple premise that underpins the book but, of course, it became a lot more complex when we started to put it together.

How did you go about choosing just 200 pictures from all of the thousands you had access to?

Dan: We knew that 200 pictures would be the limit that we could physically fit into a book, which we could produce at a price point of £25 and which wouldn't weigh so much that if someone dropped it on their foot they’d sue us for a broken toe. So, we effectively had about 200 beats to get from Point A to Point B. We had a wish list of the historical greatest hits but had to be cognisant of a lot of different factors. From a structural historical point of view, we wanted to make sure that it wasn’t just a white European or American history. We wanted to make it a global history that – shock horror! – had people of colour, and women, and events that didn't just happen in Europe in it. It's the twenty-first century: you've got to write history that is appropriate to the times. And then the photographs needed to exist. We had to have access to those photographs and then there's a whole range of technical stuff that had to work.

Marina: We had to find photos that would be suitable for colourisation. When a photograph has too much texture or when it is lacking texture, it is really difficult to make the colours stick to the photo. Most of the time we had access to the photos, but many were not good for colourisation. So, we had to change our minds and choose another topic, and this happened quite a lot in the process. And that's the hard part, because sometimes you have an amazing photo that looks incredible, but it doesn't work for colourisation, so we had to change our minds and go for the second option.

Dan: But actually, I was amazed all the way through: Marina's a great person to work with because we both come from a similar space, which is quite restless, quite perfectionist, quite prepared to chuck out hours and hours of hard work because we have a better idea. I think there are a lot of combinations of working temperaments that can cause arguments, but we didn’t have a single argument when we put the book together, we always just agreed to make it better. The only arguments we had were with the production manager and the publisher begging us not to change our work again!

Was there any particular photo that you desperately wanted to include but couldn't?

Dan: There was one that we desperately wanted to include, couldn't, and then could. There are actually 202 images in the book. We really liked what ended up as the second image in the book, which is of Howard Carter inspecting Tutankhamun's tomb. We were going to include it in the 1920s chapter but that was already jam-packed full of stuff and it would have meant kicking out genuinely important history: it just wouldn't fit. And Marina kept saying ‘I wish we could’. I would agree and say, 'I know, but I just don't see how and where'. And then right at the end of the process our production manager said, 'I have two spare pages if you want to add another'.

Marina: It was such a relief!

Dan: And actually, there it is right in the front matter of the book. If we'd put it in the 1920s you could have gone past it, even though it's a great piece of colourisation, it's an amazing photo, it's an interesting story. But at the front of the book it serves as an incredible metaphor for what was about to happen. You're about to enter this world of strange and wonderful things, gleaming with incredible colours that pop from the page, and you, like Carter, are finding history afresh and anew. Hopefully you won't be cursed and die soon after prospecting it. That's where the analogyA correspondence or partial similarity.A correspondence or partial similarity. A correspondence or partial similarity. A correspondence or partial similarity. falls down I hope!

It must take a lot of hard work and a lot of research to colourise just one photo. Were there any that were particularly difficult to do?

Marina: The quality of the photos changes a lot through the book. You can actually see how the technology to take the photographs was forming over the period we decided to cover. We started the book with photos that were not so great in quality: they had too much texture or were lacking details that I had to reconstruct digitally. And then when you come to the end of the book you have those amazing photos in super-high quality, so you can see how the technology improved over time. The photos in the first few chapters were the most difficult ones to do because they had several technical issues that made the colourisation process much more difficult for me. But there are some in the other chapters as well that were difficult: they had super quality, but they had too many details and I had to spend three or four days working on them. The one of the nine kings in the 1900s took me almost a week to finish because I had to identify each medal and each detail on the uniforms and make sure that I had all the colours right. There's so much going on inside that room and I had to evaluate and identify every little tiny detail to make sure that I had the right colour. But that's why it's one of my favourites, because it was so satisfying to see the photo in colour after spending so many hours working on it.

Were there any that were emotionally difficult to do, that you found particularly upsetting to do?

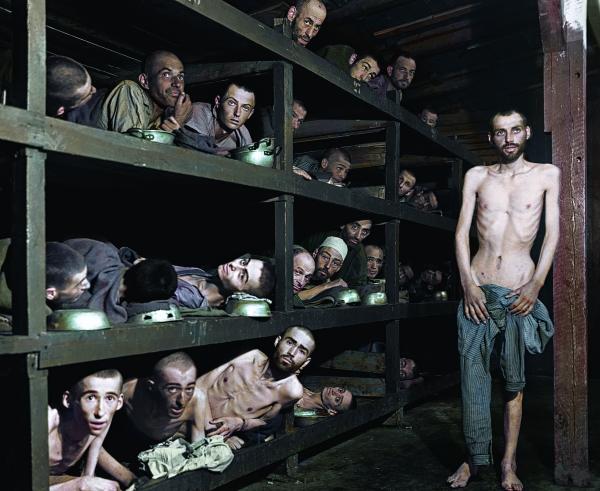

Marina: I think the one of the HolocaustThe mass murder of Jews and other minority groups under the Nazi regime.The mass murder of Jews and other minority groups under the Nazi regime.The mass murder of Jews and other minority groups under the Nazi regime. was the most difficult because you can see those people in the most vulnerable time of their lives. And I had to do something quite different. I had to choose colours that would represent the skin tones of people who were sick and that were subjected to the most horrible things. I couldn’t use too many red colours or pinks or oranges. I had to choose colours that were more bluish and yellowish to represent what they went through. It's impossible not to spend too many hours working on the photo without feeling attached to the subject. It took me, I think, twelve hours to finish it. I wanted to finish it as soon as possible because it was really difficult to look at the faces and I always kept thinking about what they went through and how awful it must have been.

There are people who argue that one should leave black and white photography as it is. How would you answer them?

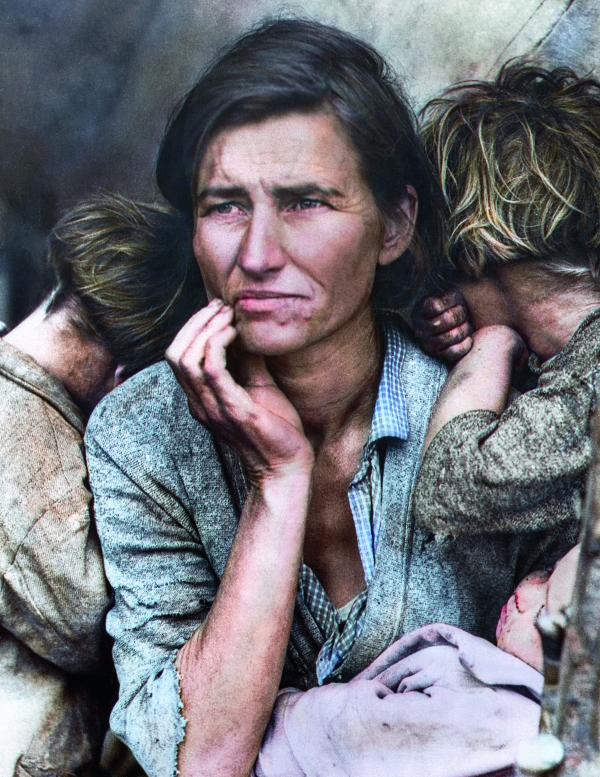

Dan: No one's forcing them to look at it, and the photo itself has not been damaged. No photos were damaged in this process. It is a purely digital process. And it's important that colourisation - I say this as an observer and not as a technician - should challenge. I think it's a form of art that should challenge you in different ways to look at the subject. Take Dorothea Lange's world-famous photo 'Migrant Mother': I think a lot of people would say 'whoa, hang on a second: that's one of the greatest black and white photographs ever taken. What are you doing?' It's like going to the Sistine Chapel with a spray can and drawing a moustache on God. But this is not vandalism; it's an historical artistic process and it should challenge you to think about the subject, which should challenge you to think about the purpose and meaning of the photograph. It is something that enhances and adds dimensions of thought as well as dimensions of ascetics to the subject matter. If people are really offended by it, that's great. I'm not addicted to causing controversy by any means, otherwise I'd have stuck to writing about Richard III. But I do think a little bit of debate about technique is healthy and important, and it's part of the point.

Speaking of Richard III, how have you found moving from the Middle Ages to the very modern?

Dan: I've written seven or eight books about the Middle Ages and it's my home subject, where I'm comfortable and happy. But I've also got a broader-ranging personal interest and I read a lot of modern history. I love new ways of bringing history to people - in the TV work I do it's not just limited to the Middle Ages. I wanted to work with Marina because I thought her work was absolutely incredible. It could have been Bronze AgeThe Bronze Age was a time between the Neolithic and the Iron Age, which is characterised by the use of the alloy bronze. In Britain it lasted from about 2500BCE until about 800BCE.The Bronze Age was a time between the NeolithicThe 'New Stone Age'. See 'The Chronology of the Stone Age'. and the Iron AgeThe Iron Age of the British Isles covers the period from about 800BCE to the Roman invasion of 43CE, and follows on from the Bronze Age., which is characterised by the use of the alloy bronze. In Britain it lasted from about 2500BCE until about 800BCE.The Bronze Age was a time between the NeolithicThe 'New Stone AgeThe earliest part of human prehistory, running from about 3.3 million years ago until (in Britain) about 2500BCE. It is defined by the use of stones (rather than metals) as tools.'. See 'The ChronologyThe arranging of events in the order they occurred in time. of the Stone Age'. and the Iron AgeThe Iron Age of the British Isles covers the period from about 800BCE to the Roman invasion of 43CE, and follows on from the Bronze Age., which is characterised by the use of the alloy bronze. In Britain it lasted from about 2500BCE until about 800BCE.The Bronze Age was a time between the NeolithicThe 'New Stone AgeThe earliest part of human prehistoryThe time in the past that happened before history began to be recorded., running from about 3.3 million years ago until (in Britain) about 2500BCE. It is defined by the use of stones (rather than metals) as tools.'. See 'The ChronologyThe arranging of events in the order they occurred in time. of the Stone Age'. and the Iron AgeThe Iron Age of the British Isles covers the period from about 800BCE to the Roman invasion of 43CE, and follows on from the Bronze Age., which is characterised by the use of the alloy bronze. In Britain it lasted from about 2500BCE until about 800BCE. archaeologyThe study of the things humans have left behind. See 'Some Notes of Archaeology'.The study of the things humans have left behind. See 'Some Notes of Archaeology'.The study of the things humans have left behind. See 'Some Notes of ArchaeologyThe study of the things humans have left behind. See 'Some Notes of Archaeology'.'.The study of the things humans have left behind. See 'Some Notes of ArchaeologyThe study of the things humans have left behind. See 'Some Notes of Archaeology'.'. or molecular physics and I would have worked on what I needed to know to work with her, because I think she's great. Actually, I found it like a palate cleanser to do a project that was completely out of my comfort zone. I pushed myself, challenged myself, not only in terms of researching the historical context and the subject matter, but also the technical skill of helping to construct a narrativeA story; in the writing of history it usually describes an approach that favours story over analysis.A story; in the writing of history it usually describes an approach that favours story over analysis. A story; in the writing of history it usually describes an approach that favours story over analysis. A story; in the writing of history it usually describes an approach that favours story over analysis. , to build a book, to work visually instead of just purely in terms of literary sources, to investigate archives, to learn the history of photography. All that stuff was like an educational holiday from the Middle Ages. But I'm back to annoying Ricardians again now, and I'm working on another medieval book.

Are you free to talk about that?

Dan: I'm actually not annoying Ricardians! I'm writing about the Crusades, which will be my book for next year. I'm halfway through the book – called Crusaders – at the moment. It's a very human history of the Crusades, told through the interlocking experiences of individuals, with their stories crossing over. And it does share a sensibility with the Colour of Time in that it is a history from all angles: Greek Christians, Latin Christians, Shiites, Sunnis, Jews, 'pagans', women, children, all people who were touched by or involved in the Crusades. It's a pluralist and long view approach to the Crusades, looking at the idea of crusading as well. The main narrative will probably stop in 1492, but it will carry on beyond that because we're still talking about the idea of crusading then.

Marina, what will be your next project?

Marina: I want to work on a second book. I don't know when it's going to happen, but it's one of my plans. Maybe the Colour of Time 2. We have enough photos to create three, four, or five books really.

Would the second volume be structured in the same way, or would you look at doing it differently?

Dan: We're not going to do dinosaurs, obviously, or the Middle Ages! This book is already quite successful. A second book would not be illogical. The subject matter you could probably predict from the availability of photography and through a quick think about the market for non-fiction. We could be working on this forever really, there's so much there. It's just about thinking what tells a great story.

One final question: if you go to any place in time to witness any event or meet any person, what would it be and why?

Dan: I would have to go somewhere in the Middle Ages. The character I'm still fascinated by that I haven't written about is Henry V so, in the name of research, I think I'd go and hang somewhat back from the hail of arrow shots at Agincourt and just see what Henry V was all about. We know the Shakespearean version of Henry V, with great oratorical flourishes and urging his men into battle and all the high poetry, but this contrasts somewhat with another account of the Battle of Agincourt in which Henry V's words to his troops were 'fellas, let's go.' So, I'd like to see what actually went on there.

Marina: I'd love to have a few minutes to chat with Albert Einstein. It would be amazing to have the opportunity to meet someone who changed the world so much. I think I'd want to ask him a few questions and spend some time with him and understand the way he saw the world. That would be fascinating.

Competition time!

We have a signed copy of The Colour of Time to give away! See our Twitter page to enter. Closing date is 15 November 2018.

For those unwilling to wait, The Colour of Time can be purchased from all good book shops today.

- Log in to post comments