Diarmaid MacCulloch: In Conversation

Diarmaid MacCulloch is Professor of the History of the Church at the University of Oxford, a Fellow of the British Academy, and has presented several programmes on the history of the church, and the Tudors for BBC 2 and BBC 4. He has also written extensively on the Tudor period, including his award-winning books on Thomas Cranmer, and A History of Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years. In 2012 he received a knighthood for services to scholarship.

Diarmaid MacCulloch’s latest book is a biography of Henry VIII’s infamous minister, who oversaw the Dissolution of the MonasteriesA set of administrative and legal processes between 1536 and 1541 that disbanded the Catholic monasteries, priories, convents and friaries in England, Wales and Ireland. It including taking their income and property and dismissing their members.A set of administrative and legal processes between 1536 and 1541 that disbanded the Catholic monasteries, priories, convents and friaries in England, Wales and Ireland. It including taking their income and property and dismissing their members.A set of administrative and legal processes between 1536 and 1541 that disbanded the Catholic monasteries, priories, convents and friaries in England, Wales and Ireland. It including taking their income and property and dismissing their members.A set of administrative and legal processes between 1536 and 1541 that disbanded the Catholic monasteries, priories, convents and friaries in England, Wales and Ireland. It including taking their income and property and dismissing their members. and the downfall of Anne Boleyn, Thomas Cromwell. This extremely detailed and insightful biography promises to shake up studies of the early English Reformation, Henry VIII, and Cromwell himself, and is likely to remain the go-to text for many years. Professor MacCulloch was generous enough to find time in his busy schedule to spend half an hour talking to us about the man, the king, the court, and the ReformationThe split from the Roman Catholic Church of protestants, inspired by people such as Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Huldrych Zwingli.The split from the Roman Catholic Church of protestants, inspired by people such as Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Huldrych Zwingli.The split from the Roman Catholic Church of protestants, inspired by people such as Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Huldrych Zwingli.The split from the Roman Catholic Church of protestants, inspired by people such as Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Huldrych Zwingli..

I would like to talk to you about your new book, Thomas Cromwell: A Life. Why Cromwell – or 'Crummle', as I should say?

Yes, we had better explain that! It's spelt ‘Cromwell’ these days and everyone pronounces it ‘Cromwell’, but as I went through thousands and thousands of Tudor letters I noticed that the people who wrote to him actually spelled his name differently. They spelled it ‘Crumwell’ and when you say the name a lot, as I have done over the last few years, you find that if you say 'Crumwell' it's very difficult to pronounce the ‘w’; much more difficult than trying to pronounce it with the 'o' sound. Try saying it, and you'll see that you lose the ‘w’. That makes me think that in the sixteenth century when these people were spelling it with a ‘u’ they pronounced it 'Crummle', so I've been pronouncing it like that. There is another Cromwell in history, Oliver Cromwell, who is a descendant - via his sister - of Thomas Cromwell, but his fame is in the mid-seventeenth century and I think that by that time the name was pronounced ‘Cromwell’ because that's how it was spelt.

I started on Thomas Cromwell because you can't avoid him in the early sixteenth century; he was the most significant minister of Henry VIII. He was the person who did so much to change the kingdom of England and the kingdom – as it became – of Ireland, too, so he's really significant in the English story. If you survey England in 1500 and then survey it in 1600 you find it's a very different place. Most of the changes that happened were in the 1530s, which was the decade in which Thomas Cromwell was chief minister of Henry VIII.

You come down very much on the side of Cromwell being a reformistSupporting the European Reformation of religion, where Protestants split from Catholic beliefs and practices, or supporting reform in a more general way.Supporting the European Reformation of religion, where Protestants split from Catholic beliefs and practices, or supporting reform in a more general way.Supporting the European Reformation of religion, where Protestants split from Catholic beliefs and practices, or supporting reform in a more general way.Supporting the European Reformation of religion, where Protestants split from Catholic beliefs and practices, or supporting reform in a more general way., rather than Geoffrey Elton's idea of his religion being the nation state. Geoffrey Elton was the pre-eminent Tudor historian of his day and a strong advocate of the importance of political history. Do you think that government was as important to Cromwell as religion, or do you think it was secondary?

Geoffrey Elton was the pre-eminent Tudor historian of his day and a strong advocate of the importance of political history. Do you think that government was as important to Cromwell as religion, or do you think it was secondary?

Religion was the main thing and it is difficult for us in the twenty-first century to realise just how all-pervasive religion was. You really need an effort of imagination not to believe in God or the afterlife, so naturally it was going to be important and it was particularly important to Thomas Cromwell. He has often been portrayed by those who don't like him - and some admirers too - as a very secularNot connected with religious matters.Not connected with religious matters.Not connected with religious matters.Not connected with religious matters. figure; he wasn't very interested in religion, he just used it. You mentioned Geoffrey Elton, who was my old doctoral supervisor, and Geoffrey was mostly interested in what Thomas Cromwell did in government and absolutely immersed himself in the archive. He revelled and gloried in going through papers that no one else had seen or taken notice of and they were all administrative papers. But if you take the whole man you see a man who took risks for religion and that doesn’t happen if you don't care about it. So, my Thomas Cromwell is a religious man with a very particular set of convictions, which are what we call ‘protestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation.Someone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation.Someone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. Reformation.Someone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. Reformation.’. In other words, he's a man of the Reformation which tore Europe apart in the sixteenth century. I actually have another jargony word for protestant – because English people didn't start using the word ‘protestant’ until the mid-sixteenth century and he's early sixteenth century – I use the word they used at the time: 'evangelical'. So, Thomas Cromwell was an evangelical and he was doing this at a time when the Catholic Church was still powerful. Thomas Cromwell constantly pushed Henry's break with Rome towards being a protestant reformation. So that's the story which I was uncovering; that's the way I looked at the documents, and it was very different from my old doctoral supervisor’s approach.

You also have Anne at the court of Henry VIII, who was very evangelically minded, yet you believe that they did not get on?

The traditional story is that Anne Boleyn - 'Bullen' I'm afraid I call her - who was going to be the second wife of Henry VII, and Cromwell were allies because they were obviously on the same religious side. It’s an extraordinary long-established picture. It goes right back to the first historians of the English Reformation, John Foxe in particular, who by a process of not really talking about their relationship gave the impression that they were allies, because it was easier: it just made the story simpler for these two heroes of the ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. Reformation to be to be allies, to work together. What I've discovered is that they didn't. They loathed each other, which of course complicates the story but also makes it more interesting. You have to remember that just because people share the same sort of ideological outlook, or religion, or politics they don't have to like each other, and modern British politics demonstrate that only too well. Anne Boleyn and Thomas Cromwell did not like each other because Thomas Cromwell did like someone else very much indeed, and that was his old boss Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. The person who really destroyed Cardinal Wolsey, under Henry VIII, was Anne; Anne took Wolsey as her enemy, as Wolsey failed at the impossible, which was to end Henry's first marriage to Catherine of Aragon. No one could have done it, but Anne blamed him, and she was responsible really for poisoning the king's mind as much as she could. So, Cromwell hated her for that, and, of course, he got his revenge because eventually Anne Boleyn fell from power and was executed. I see Thomas Cromwell as very much behind that.

How do you think this fits into arguments about faction at the court of Henry VIII?

Faction: there's an old chestnut that people have had to write essays on since I was a lad! Of course there was faction. Of course there were groups of people who liked each other, went out for meals together, drank together, and hated other people together, and that's a faction. And you have a king who has a very powerful personality but who’s also very easily swayed, if you know how. So these factions had to work around him but they're not always tidily about, for instance, religion. That's one of the views of faction which has been taken in the past: that there's a religious Protestant faction, there's a Catholic faction, and so on and so forth. Actually, if you look at the faction which got Thomas Cromwell into power under the king – and undoubtedly there was such a faction – they were the people who liked Cardinal Wolsey and who didn't like Anne. If they were going to survive at court, they would have to go along with the king's determination that she should become wife number, well 'one' in his case, but in fact wife number two, but they didn't like her. They are all Wolsey's friends, and there are people who are not Wolsey's friends around Anne who are her faction, including, for instance, her uncle Thomas Howard duke of Norfolk. His religious views were very conservative and yet he backed Anne because his niece was going to become queen. These are complicated human aspirations, human wishes to get on, and you should never simplify them. But factions were there and you just can't ignore that fact.

Do you think that Cromwell was good at swaying Henry; could Henry be easily led?

Yes. Henry was a very complicated man with emphatic opinions which could always change; you could always push him if you knew how. I say 'always': you could have a good go at pushing him in a particular direction, but if he noticed you doing it you were in dead trouble. And that's one of the reasons I think that so many people fell in his regime: he suddenly decided ‘I'm being pushed enough, you're a problem, get out'. You could interpret Thomas Cromwell's fall like that. You needed to know how to do it, and there were lots of ways of getting at Henry VIII. Obviously, if you've got any sense, you get him in a good mood. I remember years ago, before I did this research, I found a wonderful example of that: a set of villagers came up from a tiny, tiny village in Suffolk because they had a grievance and they wanted to see the king. They had a friend who was a cook at court and he said to them, ‘You need to stand beside the tennis court in the royal palace and wait until the king's won and comes out in a thoroughly good mood, and then you present him with your petition'. I thought it was wonderful. Clearly Thomas Cromwell did that sort of thing, as they all did. They looked for the king in a good mood. But because Cromwell had this very intense relationship with Henry VIII, as had his predecessorA person who held a job or office before the current holder; or the thing that came before something else. A person who held a job or office before the current holder; or the thing that came before something else. A person who held a job or office before the current holder; or the thing that came before something else. Thomas Wolsey, they could also operate in different circumstances. There is a story told by one of Thomas Cromwell's enemies, which that enemy thought discredited him, but which I think makes him seem rather subtle. This enemy of Cromwell said that he and his fellow courtiers would be standing around while Thomas Cromwell and the king were in the king's private apartments in a different room. They could hear a row going on through the door: voices raised, and raised even more because both men – Thomas Cromwell and the king – had quick tempers. The row would get worse and worse and then it would end with a slap and silence would fall. And Thomas Cromwell would walk out of the room into the middle of the courtiers, rubbing his cheek and smiling. The psychology is that he had to let the king win and the whole row would culminate in this slap. You couldn't slap the king back for obvious reasons and the king thought he had won. But the next day, Thomas Cromwell could go back when the king was in a better mood and say, 'Your grace can we just think about that a bit more'. He could do what another of his servants called 'tempering the king', changing the king's mood, which is a subtle business. That's how you run Henry VIII; that's how you manage him.

Could you talk me through your research process; it is a very interesting story, and I believe you spent five years on it?

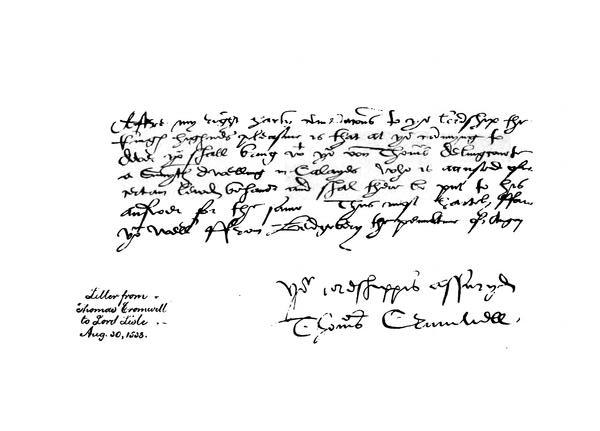

The text reads: After my right hearty commendations to your Lordship the Kings highness's pleasure is that at your coming to Dover you shall bring with you one Thomas Delingcourt a smith dwelling in Calais who is accused of certain lewd behaviour and shall there be put to his answer for the same. Thus most heartily fare you well. From Bedgebury, the penultimate of August. Your Lordship's assured, Thomas Cromwell.

The text reads: After my right hearty commendations to your Lordship the Kings highness's pleasure is that at your coming to Dover you shall bring with you one Thomas Delingcourt a smith dwelling in Calais who is accused of certain lewd behaviour and shall there be put to his answer for the same. Thus most heartily fare you well. From Bedgebury, the penultimate of August. Your Lordship's assured, Thomas Cromwell.I spent five years with the manuscriptsBooks, documents, or piece of musics written by hand rather than typed or printed. Later, pieces of work that have not yet been published.Books, documents, or piece of musics written by hand rather than typed or printed. Later, pieces of work that have not yet been published. Books, documents, or piece of musics written by hand rather than typed or printed. Later, pieces of work that have not yet been published. Books, documents, or piece of musics written by hand rather than typed or printed. Later, pieces of work that have not yet been published. in the National Archives and in the British Library; two huge archives which hold the letters and papers of Thomas Cromwell that were confiscated at his arrest and death by the king. But there are thousands and thousands of them and how do you go through them? In my very early days as a postgraduate back in the 1970s I physically went through these documents, so I know them very well. But you don't have to do that these days because they're now online, although most will not get the chance to look at them because you have to pay a large sum of money to get into this website, called State Papers Online. But luckily, the Bodleian Library in Oxford have a subscription to it, so I could go through them for free sitting at home with my laptop and a cup of tea. I did visit the National Archives, of course, and the British Library. But that wasn't necessary for most of these: you have the original document on your screen, the handwriting, the manuscript, and I sat there and I went through them more or less day by day from the earliest archives we have through to the moment he was arrested and, afterwards, the very last letters he wrote in The Tower of London beseeching the king to set him free. So that was five years of my life and every day, at the end of the day, as it got towards seven o'clock or so, I felt so weary, and I thought that actually put me in exactly the same position as Thomas Cromwell when he was reading these letters. The noise that came out of those letters, the wheedling, the flattery, the sycophancy, the jokes, the occasional good news, and you just think of yourself at the end of a long day as the king's chief minister, with this barrage of different stuff; so many things to have to keep your eye on. It took a very great statesman-administrator-politician to handle that. And in the end of course it did for him too. After nine years he fell from power.

What do you make of Cromwell the man?

Frequently he's been seen as a sort of machine, a bureaucrat, a heartless man without emotions or passions. That's nonsense. It's difficult to recapture the man as it's difficult to recapture anyone in the past. It's particularly difficult because we don't have many of the letters he sent out. They would have been in the archive in the last draft that the clerk had written for him, but they've gone. I think his household destroyed all that before he was arrested because they thought it would incriminate him: good try, didn't work! But once you've got past that obstacle and tried to hear his voice you do get the sense of a human being with particular personalities. He clearly had a bad temper; you can see that in his famous Holbein portrait – he’s about a minute away from shouting at someone. He had a dark wit and savage sense of humour, I think, often involving threats of execution. But also, some rather engaging things: he clearly got on very well with what you might call ‘ladies of a certain age’: widows, dowager duchesses, and the like. They liked him, and he clearly gave extremely good dinner parties and they had a very good time. And that was useful to him: they could be useful, and the set of relationships they brought with them were very useful. But there is also another interesting thing: he had a very soft spot for wild young men. There’s nothing very sleazy about that; it's simply that he had been a wild young man, he'd run away from home, run away from Putney to go to Italy, and so they reminded him of his younger days. You can see it in the letters of their disapproving older relatives, saying 'I can't understand why you're giving so much time to so-and-so'. That's rather nice I think; that's not the action of a cold bureaucrat. And he adored his one surviving son, Gregory. He took risks for Gregory, and towards the end of his life and career did foolishly risky things to promote Gregory, and Gregory seems to be another of these wild young men. It's interesting: in a sense Thomas Cromwell's judgment deserted him because he was a loving father.

What do you think of the Wolf Hall version, Hilary Mantel's version, of Thomas Cromwell; do you agree?

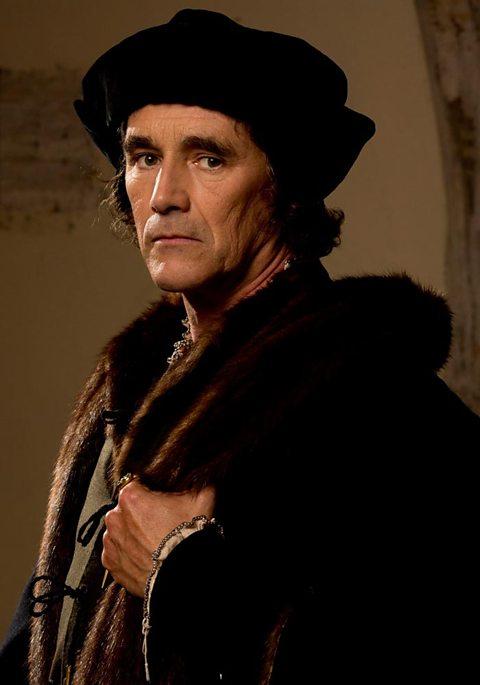

© BBC

Yes, by and large I do. Hilary Mantel and I get on very well. We've become friends as a result of both our writing projects. Independently of me she reassessed the man and came to very similar conclusions. I think she would say there was less religion in her novels than there should be. But otherwise, she really nailed it. She noticed this antagonism with Anne Boleyn and made a lot of it in novel number two. Again and again I thought, 'gosh you know so much, you really do know the background here'. She was, I think, a little unfair to Thomas More and particularly Catholic critics of her books have said that. But she would say, 'This is Thomas Cromwell's thoughts. This is a novel; it's not history.' I've tried to be fair to Thomas More. It's difficult because I like Thomas Cromwell and I have to restrain my liking and credit the other side, but there are what you might call discreditable things about More. There's darkness in More. He liked the idea of burning people at the stake for instance, and I don't! So, in things like that, Hilary and I have come to rather similar conclusions.

So what’s next?

I've always had two strands in my historical career. One has been grubbing around Tudor documents and creating this sort of book, or my biography of Thomas Cranmer. The other has been taking huge sweeps of history. So, I've written a big book on the European Reformation as a whole; a big book on the whole history of Christianity. And that's where I'm going next. The book is going to be called Sex and the Church and it is taking two- or three thousand years of the history of the church and looking at sex, family, and gender. It's a big issue in Christianity now. What I want to do is to create some sanity around that very often-heated discussion and you do that by looking at the history as calmly as you can. I'm not going to say ‘objectively’ because none of us are objective as historians - we do our best - but we try to produce a balanced picture.

Do you have a date in mind for when you want to get it finished?

Yes, the contract says Christmas 2023, so you'll have to wait until then!

A few final questions: if you could go back to any point in history when would it be and why?

Yesterday! Historians are very rarely interested in time travel backwards because we know about the dentistry. I would not want to live in any age before modern medicine!

For a visit?

I could manage a visit, I think. I would perhaps like to have an afternoon with Thomas Cromwell. Just to ask him a few things, all the missing things that I didn't know about. Like how on earth did he get such a good education in Italy? That would be fascinating, the blanks in the story.

Which historical figures would be your perfect dinner guests?

I would want Thomas Cromwell, obviously. I might put him alongside the Rev. Sydney Smith from nineteenth-century England; he was a great wit. We would also need two women: Elizabeth I would do, but probably not her mother, Anne Boleyn! The other woman could be Hildegard of Bingen; she would provide the serious conversation. Hildegard of Bingen was a twelfth-century German Benedictine abbess, who was also a composer, writer, and philosopher, and is considered the founder of scientific natural philosophy in Germany. She was named Doctor of the Church in 2012 by Pope Benedict XVI.

Hildegard of Bingen was a twelfth-century German Benedictine abbess, who was also a composer, writer, and philosopher, and is considered the founder of scientific natural philosophy in Germany. She was named Doctor of the Church in 2012 by Pope Benedict XVI.

Diarmaid MacCulloch’s excellent book, Thomas Cromwell: A Life is available from all good bookshops.

Competition Time!

We have a signed copy of Thomas Cromwell: A Life to give away to one lucky reader. Visit our Twitter page to find out more.

- Log in to post comments