Bethlem: A Mental Place

Key points about Bethlem Hospital

- Bethlehem Hospital was founded as a priory in 1247.

- It became the first institution dedicated to the care of the mentally ill

- Over the last 750 years, it has been rocked by scandalAn event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action.

- Bedlam, the contraction of its name, has become a by-word for insanity

- It has helped, as well as hurt, patients

People you need to know

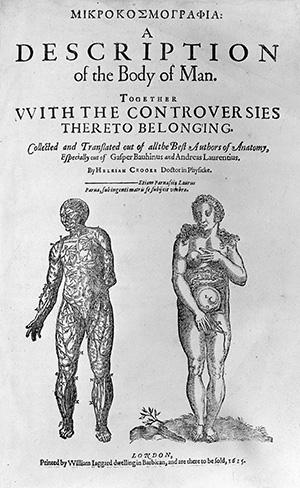

- Helkiah Crooke - respected physician, physician to James I, and keeper of Bethlem from 1619 until 1632

- Simon Fitzmary - a reasonably well-to-do Londoner who was twice sheriff of London, and founder of Bethlehem Hospital

- George III - king of England between 1760 and 1820, and known for his bouts of mental illness

- James Hadfield - would-be assassin of George III, and resident of Bethlem

- The Monro dynastyA line of hereditary rulers of a country, business, etc. - four generations of physicians-in-charge of Bethlem, consisting of James, John, Thomas, and Edward

- Ann Morley - patient of Bethlem for two months in 1850, whose treatment caused a scandal

- Margaret Nicholson - would-be assassin of George III, and resident of Bethlem

- James Norris - violent patient in Bethlem in the early nineteenth century, whose treatment and death caused a scandal

- Edward Oxford - would-be assassin of Queen Victoria and resident of Bethlem

- Lord Palmerston - sometimes ToryBritish right-wing political faction based on the values of traditionalism and conservatism. Modern Conservatives are sometimes still referred to as Tories.British right-wing political faction based on the values of traditionalism and conservatism. Modern Conservatives are sometimes still referred to as Tories.British right-wing political faction based on the values of traditionalism and conservatism. Modern Conservatives are sometimes still referred to as Tories., WhigA member of the reforming and constitutional party that sought the supremacy of Parliament over the monarchy. The party was succeeded by the Liberal Party in the nineteenth century., and Liberal politician, who was Secretary at War in 1818 and later became prime minister

- Robert Peel - Tory prime minister from 1834 until 1835, and from 1841 until 1846

- Peter Tavener - janitor in charge of Bethlem at the beginning of the fifteenth century

- Queen Victoria - queen of England between 1837 and 1901

Bethlem is a place so famous for chaos and confusion that its nickname, Bedlam, has entered the English language as a synonym for madness. But has its reputation been deserved, or has it been on the wrong end of morbid fascination and sensationalismThe presentation of stories in a way that is intended to provoke public interest or excitement, at the expense of accuracy.?

Bethlehem Hospital began its life in 1247 when Simon Fitzmary, inspired by Pope Innocent IV’s plea for help for the Church of Bethlehem, donated his estate at Bishopsgate to the order. Fitzmary felt a special affinity with the Church of Bethlehem. Legend has it that when lost in the dark while on crusade, FitzMary was led back to safety by the star of Bethlehem, which he took as his inspiration from thereon in. A priory was established on the site, which became a refuge for the poor and vulnerable, with the star of Bethlehem as its emblemA heraldic device or symbol that forms the badge of a nation, organisation, or family.. By 1327, it was considered a hospital and by the beginning of the fifteenth century, it was housing the insane. From there, it increased in size and moved premises – mainly thanks to the terrible state of its buildings – first to Moorfields in 1676, then to St George’s Fields in 1815, and finally to its current home in Beckenham in 1930.

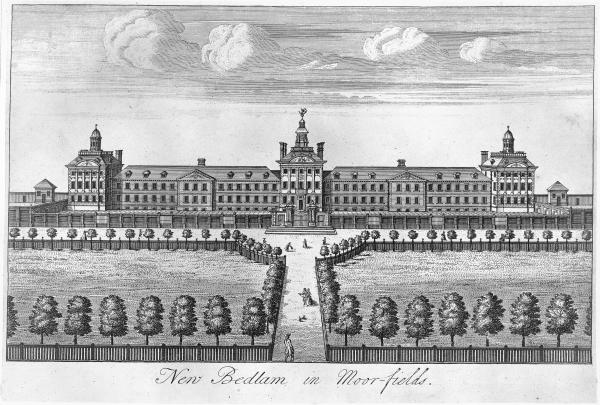

Fitzmary felt a special affinity with the Church of Bethlehem. Legend has it that when lost in the dark while on crusade, FitzMary was led back to safety by the star of Bethlehem, which he took as his inspiration from thereon in. A priory was established on the site, which became a refuge for the poor and vulnerable, with the star of Bethlehem as its emblemA heraldic device or symbol that forms the badge of a nation, organisation, or family.. By 1327, it was considered a hospital and by the beginning of the fifteenth century, it was housing the insane. From there, it increased in size and moved premises – mainly thanks to the terrible state of its buildings – first to Moorfields in 1676, then to St George’s Fields in 1815, and finally to its current home in Beckenham in 1930. In 1598, a report condemned the Bishopsgate hospital as not fit to enter. Situated between two open sewers, the city having grown up around it, it was filthy and stinking. The hospital gardens were swimming in raw sewage, fetid stagnant water, and the waste products from nearby industry. Nor was the inside of the hospital any better: the rank air permeated everything, and the gallery and cells were unfit for human habitation. The move to Moorfields should have been a change for the better: the new grand building had cost £17,000 to build, was considered an architectural marvel and was listed in at least 36 tourist guides of London. Marvellous it may have been, but well-built it was not, and by 1800, the roof leaked, the upstairs had no water (aside from that dripping down the walls), and the building was subsiding. During the seven and a half centuries since its foundation, it has changed hands even more frequently than premises, being managed by the order, the City of London, the Crown, Bridewell Prison, and currently by the Bethlem Royal Hospital, South London, and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust.

In 1598, a report condemned the Bishopsgate hospital as not fit to enter. Situated between two open sewers, the city having grown up around it, it was filthy and stinking. The hospital gardens were swimming in raw sewage, fetid stagnant water, and the waste products from nearby industry. Nor was the inside of the hospital any better: the rank air permeated everything, and the gallery and cells were unfit for human habitation. The move to Moorfields should have been a change for the better: the new grand building had cost £17,000 to build, was considered an architectural marvel and was listed in at least 36 tourist guides of London. Marvellous it may have been, but well-built it was not, and by 1800, the roof leaked, the upstairs had no water (aside from that dripping down the walls), and the building was subsiding. During the seven and a half centuries since its foundation, it has changed hands even more frequently than premises, being managed by the order, the City of London, the Crown, Bridewell Prison, and currently by the Bethlem Royal Hospital, South London, and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust.

A rum lot

Throughout its life, Bethlem has been home to many colourful characters – both patients and staff – as well as being the dumping ground of society’s unwanted. Poets and assassins, religious fanatics and criminals, wannabe-monarchs and depressed mothers have all graced its halls, often providing tragedy and comedy in equal measure. These people have been a source of entertainment, and inspired derision, pity, and fear in those outside the hospital’s walls.

The criminally insane

Although often housing criminals before, between 1815 and 1863 Bethlem was specifically tasked with caring for the criminally insane, including murderers, violent offenders and those threatening the public’s peace and safety. In 1853 it was home to more than 100 of the country’s 436 criminally insane population. Catherine Arnold, ‘Bedlam: London and its Mad’ London: Simon & Schuster (2008) p.200 These included the famous would-be royal assassins, Margaret Nicholson and James Hadfield, both of whom targeted George III, and Edward Oxford, who attempted to kill Queen Victoria.

Catherine Arnold, ‘Bedlam: London and its Mad’ London: Simon & Schuster (2008) p.200 These included the famous would-be royal assassins, Margaret Nicholson and James Hadfield, both of whom targeted George III, and Edward Oxford, who attempted to kill Queen Victoria.

Royal assassins

Margaret Nicholson had been a servant to the aristocracyA generic term for the highest social class., living in genteel poverty and buying clothes instead of food, until certain romanticCharacterised by expressions of love; or an idealised way of looking at something; or someone who followed the Romantic artistic movement, that focused on individualism and emotion. choices led to questions over her respectability. Unable to continue working as a domestic servant she became a seamstress, but started to experience delusions over her rank and status. At first she attempted to obtain work in the royal household, but instead ended up trying to lay claim to the throne. Things came to a head in 1786 when she approached George III on the pretext of presenting him with a petition, before trying to stab him with a cake knife. The king took pity on her and sent her to the criminal wing of Bethlem, where she was supplied with plenty of tea, gingerbread, tobacco, snuff, and writing materials, and lived out her life as a model patient. She died in 1828, aged 83.

James Hadfield was a soldier who sustained severe head injuries fighting in France. Back in England with an altered personality, he was influenced by a religious fanatic, Bannister Truelock (who also ended up in Bethlem), and became convinced that the only thing preventing a Second Coming was George III. On 15 May 1800, Hadfield shot at George III with a pistol in Drury Lane Theatre. He missed and was captured, was put on trial and found not guilty by reason of insanity. He was sent to Bethlem where, two years later, he punched another patient in the face and killed him. Shortly afterwards he escaped but was recaptured at Dover and sent to Newgate prison. After 14 years he returned to Bethlem, where he made straw baskets, selling them to visitors for between 3s. 6d. and 7s. 6d. He kept pet cats and birds, wrote poetry, and lusted after a female patient, and died in 1841.

Edward Oxford tried to shoot Queen Victoria in 1840 – although he claimed there was only powder and no shot in the pistol - and was subsequently placed in Bethlem. Just under 10 years later, another man, William Hamilton, did the same thing. Hamilton was sentenced to seven years transportation. There he started knitting and playing the violin, learnt several languages including Greek and Latin, and beat every other patient at chess. He was moved to Broadmoor in 1864, and in 1867 was considered so well cured that he was offered exile to Australia. He changed his surname to Freeman, and left for Australia where he lived and worked as a painter until his death in 1900.

Just under 10 years later, another man, William Hamilton, did the same thing. Hamilton was sentenced to seven years transportation. There he started knitting and playing the violin, learnt several languages including Greek and Latin, and beat every other patient at chess. He was moved to Broadmoor in 1864, and in 1867 was considered so well cured that he was offered exile to Australia. He changed his surname to Freeman, and left for Australia where he lived and worked as a painter until his death in 1900.

Insanely violent

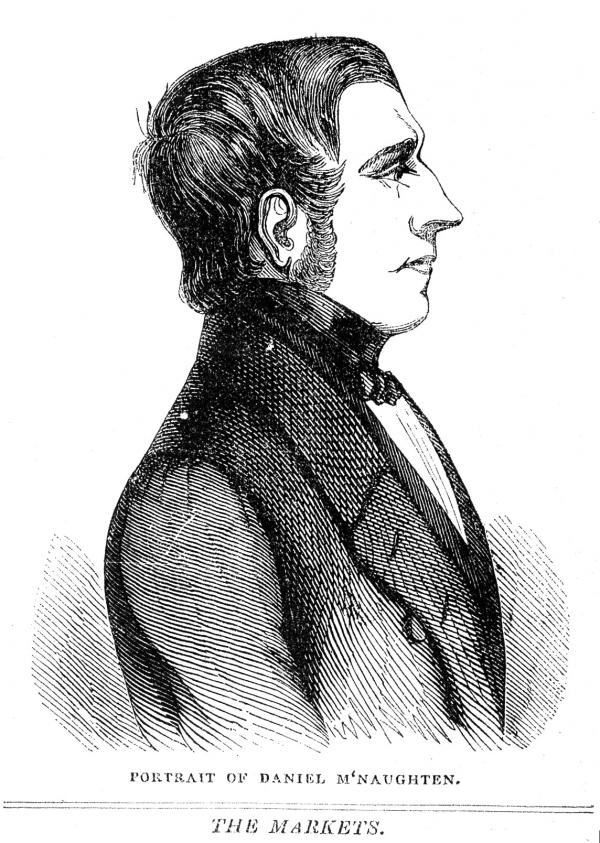

Other newsworthy violent patients included the paranoid Daniel McNaughton who, believing he was being harassed by Glaswegian Tories, attempted to shoot Robert Peel in 1843. A case of mistaken identity had him shooting Peel’s private secretary, Sir Edward Drummond, instead. McNaughton seems to have stayed quietly in Bethlem, apart from one hunger strikeWhere a prisoner refuses to eat food as a form of protest.Where a prisoner refuses to eat food as a form of protest.Where a prisoner refuses to eat food as a form of protest., which ended in his being force-fed. But by the time he was transferred to Broadmoor in 1864, he was weak and ill from diabetes and heart problems. He died the following year. Another would-be political assassin, David Davis, was a soldier who had served under Wellington in 1814. Returning home and reduced to half-pay, he begged for a pension. When this was not forthcoming he attempted suicide, chopped his penis off and sent it to Lord Palmerston (whom he blamed for the situation), and shot, but didn’t kill, Palmerston in 1818. Davis remained at Bethlem, where ‘He appears to conduct himself rationally, and never displays any symptoms of frenzy. He seldom converses with any of the other patients, but maintains towards all the most haughty reserve. He frequently bursts out in laughter without any obvious cause; but is regular, cleanly, and harmless. He receives his half-pay, about seventy pounds a year, which he spends chiefly in trifles, apple-pies, and various kinds of pastry.’ James Smyth (att.), Sketches in Bedlam, https://www.gethistory.co.uk/reference/sources/modern/georgian/sketches-in-bedlam-males

James Smyth (att.), Sketches in Bedlam, https://www.gethistory.co.uk/reference/sources/modern/georgian/sketches-in-bedlam-males

By the time Sketches in Bedlam was anonymously published in 1823, Bethlem was home to a number of ex-servicemen, who perhaps today would be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. Many were harmless – to everyone but themselves – but were obsessed either by glory or by death. One particularly sad case was Charles P. Traile, who had been a lieutenant in the 95th before discovering a horror of war, and a fear of death and particularly of being poisoned. He started refusing his food, even after someone else had tasted it, and was force-fed to ensure he didn’t starve, but was found hanged in his cell. Others were much more violent. Patrick Walsh had served in both the army and the navy, and was even close to Admiral Lord Nelson when he fell at the Battle of Trafalgar. He gained notoriety as a ringleader during the mutinyRebellion against authority, particularly of military personnel or sailors against their commanding officers. on HMS Hermione, which saw the captain and officers murdered and the ship sold to the Spanish. Once admitted to Bethlem, he was treated with a certain amount of caution but leniencyBeing more merciful or tolerant than expected.Being more merciful or tolerant than expected.Being more merciful or tolerant than expected., until he murdered a fellow patient for blasphemyThe action or offence of speaking sacrilegiously about God or a sacred thing.. Thereafter, with his bent for violence and a ‘taste for bloodshed and slaughter’,

One particularly sad case was Charles P. Traile, who had been a lieutenant in the 95th before discovering a horror of war, and a fear of death and particularly of being poisoned. He started refusing his food, even after someone else had tasted it, and was force-fed to ensure he didn’t starve, but was found hanged in his cell. Others were much more violent. Patrick Walsh had served in both the army and the navy, and was even close to Admiral Lord Nelson when he fell at the Battle of Trafalgar. He gained notoriety as a ringleader during the mutinyRebellion against authority, particularly of military personnel or sailors against their commanding officers. on HMS Hermione, which saw the captain and officers murdered and the ship sold to the Spanish. Once admitted to Bethlem, he was treated with a certain amount of caution but leniencyBeing more merciful or tolerant than expected.Being more merciful or tolerant than expected.Being more merciful or tolerant than expected., until he murdered a fellow patient for blasphemyThe action or offence of speaking sacrilegiously about God or a sacred thing.. Thereafter, with his bent for violence and a ‘taste for bloodshed and slaughter’, Smyth, Sketches, https://www.gethistory.co.uk/reference/sources/modern/georgian/sketches-in-bedlam-males he was kept under constant restraint and away from other patients.

Smyth, Sketches, https://www.gethistory.co.uk/reference/sources/modern/georgian/sketches-in-bedlam-males he was kept under constant restraint and away from other patients.

The artist Richard Dadd was another inmate who murdered for religious purposes. He killed his father whom he believed to be the devil, and was captured on his way to the Continent intending to kill the Austrian emperor. Although constantly violent during his stay at Bethlem, he was allowed access to art materials and painted two of his most famous pieces, Contradiction: Oberon and Titania, and The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke, there. In 1863, he was sent to Broadmoor, where he died of tuberculosis in 1886.

Divine madness

Not all of Bethlem’s religious fanatics were violent or criminal. One Daniel, Oliver Cromwell’s former porter, was admitted to Bethlem by the RestorationThe restoration of the monarchy and the return to a pre-civil war form of government in 1660, following the collapse of the Protectorate. authorities in 1665. He collected a considerable library of pamphlets and books, including a Bible given to him by Charles II’s mistress, Nell Gwyn, and was allowed to preach to his admirers, ‘sober matrons, clutching their Bibles and listening reverentially,’ from the window of his cell, until his death in 1667. Arnold, Bedlam, pp.80-1 Richard Farnham, a weaver from Colchester, was another who attracted a number of ‘disciples’. He made several prophesies, including the imminent end of the world and his own death on the streets of Jerusalem, after which he would rise again after three days to become a priest and king. Considered incurable but harmless, he was released from Bethlem and died – probably as a surprise to him and his disciples – at a friend’s house in 1641.

Arnold, Bedlam, pp.80-1 Richard Farnham, a weaver from Colchester, was another who attracted a number of ‘disciples’. He made several prophesies, including the imminent end of the world and his own death on the streets of Jerusalem, after which he would rise again after three days to become a priest and king. Considered incurable but harmless, he was released from Bethlem and died – probably as a surprise to him and his disciples – at a friend’s house in 1641.

Many religious fanatics were admitted to Bethlem not because they were mad, but because they were inconvenient. Pioneers of religious sects, including Ludovic Muggleton, the founder of MuggletonianismThe beliefs of a small Protestant sect, including a hostility to philosophical reason, a scriptural understanding of how the universe works, and that God takes no notice of everyday events on Earth so will not intervene (until the end of the world)., and leaders of the QuakersMembers of a Protestant sect that moved away from the established Church of England in the seventeenth century. often found themselves residing in Bethlem, as did a number of self-styled prophets. Lady Audley, also known as Eleanor Davies, was one such. A rich noblewoman, she had gained fame by correctly predicting the death of the Duke of Buckingham in 1628. However, when she started predicting the death of Charles I in 1633, she found herself on trial for treason. Following two years’ imprisonment in the Gatehouse at Westminster and a £3,000 fine she was released, but immediately began making trouble for herself again. In 1636 she very publicly disapproved of the LaudianReforms introduced to the mainly Calvinist Church of England by William Laud in the reign of Charles I, which pushed for the rejection of predestination and the belief that all men could achieve salvation. reforms of the Church and was sent to Bethlem as insane. There, she resided in the steward’s house, although she didn’t get on with her hosts, and in 1638 she was moved to the Tower. Eventually released, she continued to write for the rest of her life, dying in 1652.

An inconvenient truth

Any criticism of the government could result in consequences similar to Lady Audley’s. It was much easier to declare a critic insane than to address legitimate concerns. An Elizabethan diarist wrote in 1595 that ‘A certain citizen, being a silkweaver, came to the Lord Mayor's house, using some hard speeches concerning him and in dispraise of his government. The Lord Mayor said he was mad and so committed him to Bedlam as a madman.’ Roy Porter, ‘Bethlem/Bedlam: Methods of Madness?’, History Today 47 (1997) Richard Stafford, who published tracts as a scribe of Jesus and then denounced William III as a usurper, was quickly diagnosed as insane and sent to Bethlem in 1691. Richard Jenkins, a Welsh labourer who was impressed to the navy, was committed by the Admiralty to a madhouse, where he was constantly kept in chains, before he was admitted to Bethlem in 1818. His main symptom was criticising the navy as corrupt and dishonourable, accusing officers of using loopholes to ensure advancement for their offspring, and of misappropriation of provisions. Jenkins refused to be silent, perhaps even refusing to be paid off, and believed that the Admiralty intended to silence him more permanently. Instead, the Admiralty called him delusional and dangerous, although the author of Sketches in Bedlam reported that ‘he has been here under no restraint whatever, nor has he ever done any mischief.’

Roy Porter, ‘Bethlem/Bedlam: Methods of Madness?’, History Today 47 (1997) Richard Stafford, who published tracts as a scribe of Jesus and then denounced William III as a usurper, was quickly diagnosed as insane and sent to Bethlem in 1691. Richard Jenkins, a Welsh labourer who was impressed to the navy, was committed by the Admiralty to a madhouse, where he was constantly kept in chains, before he was admitted to Bethlem in 1818. His main symptom was criticising the navy as corrupt and dishonourable, accusing officers of using loopholes to ensure advancement for their offspring, and of misappropriation of provisions. Jenkins refused to be silent, perhaps even refusing to be paid off, and believed that the Admiralty intended to silence him more permanently. Instead, the Admiralty called him delusional and dangerous, although the author of Sketches in Bedlam reported that ‘he has been here under no restraint whatever, nor has he ever done any mischief.’ Smyth, Sketches, https://www.gethistory.co.uk/reference/sources/modern/georgian/sketches-in-bedlam-males The greatest complaint about him was his singing of sea shanties.

Smyth, Sketches, https://www.gethistory.co.uk/reference/sources/modern/georgian/sketches-in-bedlam-males The greatest complaint about him was his singing of sea shanties.

Patient care

So, what can be learnt about the care and treatment of patients at Bethlem from the above case studies? What is immediately apparent is that, whatever the rumours, not all patients were locked up and abused. Many had access to art materials, music, and books, and patients were encouraged to discover and enjoy hobbies. The author of Sketches, who displays such a familiarity with Bethlem and its patients that he must have worked there, speaks fondly and with sympathy of those residing within its walls. This is despite the fact that for anyone with any compassion, working at Bethlem must have been hard. As the authors of Sketches describes:

The duties of the keepers, both male and female, are certainly very arduous. They have the violent to restrain, the low and melancholy to cheer, the deluded to undeceive, the filthy to cleanse, the helpless to dress, undress, and feed, the ill-tempers of all to bear; and, in fact, their occupation is one of perpetual anxiety, watchfulness, and alarm. Many of the patients are ever contriving to obtain means for self-destruction, the prevention of which in itself is a most anxious task, and requires the utmost vigilance. A keeper here, in fact, should possess vigilance, courage, strength, and patience, to be able to accommodate himself to all the tempers, whims, and occasions.

Smyth, Sketches, https://www.gethistory.co.uk/reference/sources/modern/georgian/sketches-in-bedlam-introduction.

The day-to-day care of patients varied depending on the era and the style of management. During the first hundred years of the hospital’s life, it was so poor that the order would go out begging for alms, and those staying at the hospital had little more than bread, ale and cheese to sustain them, and straw to sleep on. This gave rise to the idea of Tom O’Bedlam, the poor mad wretch wandering the countryside in the hope of charity, and it became so fixed in society that by the reign of the Tudors, the identity had been adopted by many looking to make some money out of it, and it was even possible to purchase fraudulent certificates authenticating their Bethlem heritage. It was only in 1675 that the governors tackled the problem and announced that former patients were never sent out begging by the hospital. In the Tudor and Stuart era, those patients not considered dangerous, were able to wander the hospital as they pleased, and possibly also had access to the immediate locality. They survived on a deliberately reduced, plain diet

This gave rise to the idea of Tom O’Bedlam, the poor mad wretch wandering the countryside in the hope of charity, and it became so fixed in society that by the reign of the Tudors, the identity had been adopted by many looking to make some money out of it, and it was even possible to purchase fraudulent certificates authenticating their Bethlem heritage. It was only in 1675 that the governors tackled the problem and announced that former patients were never sent out begging by the hospital. In the Tudor and Stuart era, those patients not considered dangerous, were able to wander the hospital as they pleased, and possibly also had access to the immediate locality. They survived on a deliberately reduced, plain diet This being considered a treatment for madness, which, at times, was thought to be a result of over-indulgence. of beer, bread, oatmeal, and alternating dairy and meat. This was supplemented by gifts from friends and alms from the community. By the Georgian period, patients were kept inside the walls of the hospital, although were able to use the attached exercise yard. The diet was still plain, although allowance was made in the form of tea and other luxuries, for wealthier patients for an additional charge.

This being considered a treatment for madness, which, at times, was thought to be a result of over-indulgence. of beer, bread, oatmeal, and alternating dairy and meat. This was supplemented by gifts from friends and alms from the community. By the Georgian period, patients were kept inside the walls of the hospital, although were able to use the attached exercise yard. The diet was still plain, although allowance was made in the form of tea and other luxuries, for wealthier patients for an additional charge.

Foreign visitors to the hospital were impressed by the quality of care and cleanliness. In 1788, a French visitor commented that:

I stayed for some time in Bedlam. The poor creatures there are not chained up in dark cellars, stretched on damp ground, nor reclining on cold paving stones, when a moment of reason succeeds to delirium. When they seem to be awakening from a long dream, there is nothing to recall their pitiable condition – no bolt, no bars. The doors are open, their rooms wainscoted, and long airy corridors give them a chance to exercise. A cleanliness, hardly conceivable unless seen, reigns in this hospital. Five or six men maintain this cleanliness, assisted by the patients themselves, when they begin to come to themselves, who are rewarded by small presents.’

E.G. O’Donoghue, The Story of Bethlehem Hospital from its Foundation in 1247, London: T Fisher Unwin (1914) p.282

Bethlem, it would seem, was better than many similar institutions on the Continent. It was also often no worse than other institutions in Britain. Cruel treatment was common in private madhouses during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many of which put profit before patients, had no legal restrictions placed on them, and became ‘mansions of misery’. Arnold, Bedlam, p.125 In 1772, the owners of Bethnal Green madhouse were tried for illegally incarcerating the wife of an abusive husband, and threatening to disembowel her if she resisted. She, and other ladies in the house, were chained, starved, whipped, verbally abused and otherwise threatened. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, York Asylum was accused of forging records to conceal the deaths of patients, embezzlement, rape, and murder. When an inquiry was launched, the asylum mysteriously burnt down, taking all the paperwork, and four patients, with it. One Victorian ‘expert’ in female madness, who operated from his own private practice in London, performed genital mutilation on women, including epileptics, disobedient 10-year-old girls and women seeking divorce. Compared to these instances, regular meals and opportunities for exercise and the pursuit of hobbies seem progressive and compassionate.

Arnold, Bedlam, p.125 In 1772, the owners of Bethnal Green madhouse were tried for illegally incarcerating the wife of an abusive husband, and threatening to disembowel her if she resisted. She, and other ladies in the house, were chained, starved, whipped, verbally abused and otherwise threatened. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, York Asylum was accused of forging records to conceal the deaths of patients, embezzlement, rape, and murder. When an inquiry was launched, the asylum mysteriously burnt down, taking all the paperwork, and four patients, with it. One Victorian ‘expert’ in female madness, who operated from his own private practice in London, performed genital mutilation on women, including epileptics, disobedient 10-year-old girls and women seeking divorce. Compared to these instances, regular meals and opportunities for exercise and the pursuit of hobbies seem progressive and compassionate.

A caring institution?

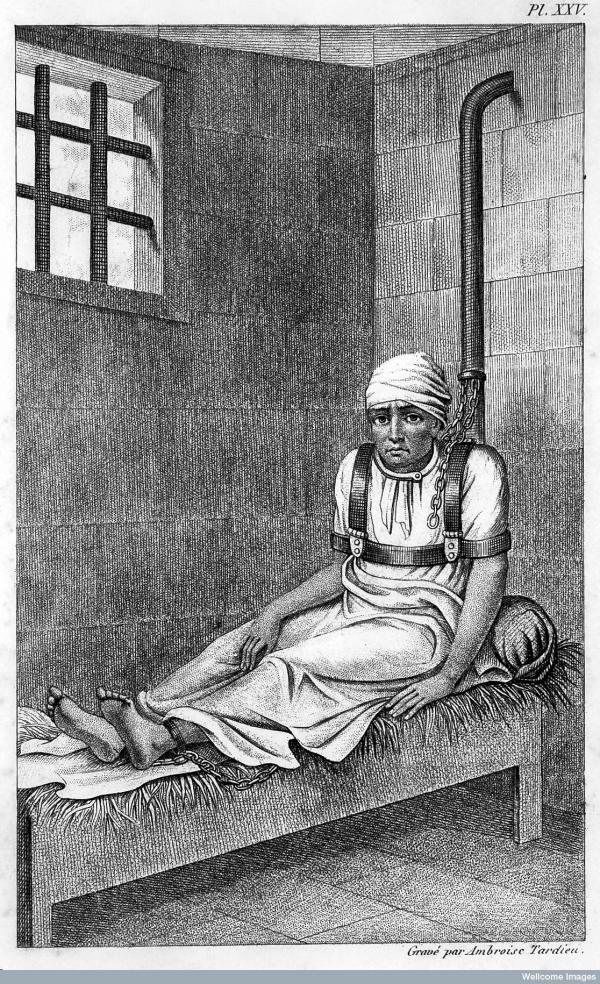

Not all patients were easy to deal with nor cared for properly. Restraint was an obvious issue. Patrick Walsh’s restraints were ‘an iron cincture that surrounds his waist, with strong handcuffs attached to it, sufficient to check his powers of manual mischief, but with liberty enough for all his requisite occasions of food, drink, taking snuff, &c. &c. Such are the means for his restraint by day: not painful to him, but merely for the safety of others. At night it is found necessary to fasten him by one hand and leg to his bedstead, with strong locks and chains.’ Smyth, Sketches, https://www.gethistory.co.uk/reference/sources/modern/georgian/sketches-in-bedlam-males In addition, his doors were double-bolted and reinforced, to prevent him breaking them down to get to the other patients.

Smyth, Sketches, https://www.gethistory.co.uk/reference/sources/modern/georgian/sketches-in-bedlam-males In addition, his doors were double-bolted and reinforced, to prevent him breaking them down to get to the other patients.

A similar instance of restraint caused national outrage, when a Quaker philanthropist discovered, on a visit to Bethlem in 1814, a man who had been held in tight restraints for 10 years. James Norris was an American marine who had been referred to Bethlem by the Office for Sick and Wounded Seamen. Extremely violent, he had stabbed a keeper and a patient who went to the keeper’s aid, and bitten the fingers off another patient. Saying they had no other means to control him or to protect those living and working in Bethlem, staff devised a harness in which Norris was barely able to move. His whole body was tightly secured in a contraption where his arms and legs were restrained, his waist was chained, an iron bar was wrapped around his body with another one around his neck, and these were connected to a six foot long vertical bar. A chain ran from his ‘collar’ to a partition, which enabled his keepers to move him whenever they wanted. On the positive side, he was allowed a pet cat, books and paper. This did him little good. During an investigation into practices at Bethlem and other asylums in 1815, James Norris died. Bethlem initially blamed tuberculosis but a post-mortem revealed that he’d died from extreme constipation. His inability to move had stopped his bowels from working, and they had eventually split.

Force-feeding, although likewise deemed necessary by hospital staff, was deeply intrusive and unpleasant. Sketches provides a description of the process:

At last recourse to the elastic bottle and tube were found absolutely necessary to keep him alive. This bottle was formed of India rubber, with an elastic leathern pipe attached, about twenty inches long. The bottle was filled with rich broth, to which eggs beaten up and some wine were added. The pipe was passed up his nostril, through the palate of his mouth, by which means the nutriment was conveyed to his stomach; and this operation was performed daily for some time...

Smyth, Sketches, https://www.gethistory.co.uk/reference/sources/modern/georgian/sketches-in-bedlam-males

The fact that force-feeding was necessary to break hunger strikes is also worrying: what were the conditions that made such strikes necessary? Admittedly, many patients were not happy to be in Bethlem, but it takes determination and a sense of righteousness to continue a hunger strike to the point where force-feeding becomes necessary.

The above instances were, perhaps, kindly meant and came about through a lack of knowledge of modern medicine, but not every instance could be excused in this way. Throughout Bethlem’s history, it has been haunted by charges of abuse and neglect, where patients have been left cold, hungry, dirty, and naked. In 1403, patients were found to be locked away, made to buy their own food and drink, bullied by the keeper’s wife, deprived of sleep, and given no treatment. Later, in 1625, an inspection found the patients starving and cold, without the necessary means to cover themselves and denied access to the only fire in the entire building. Inmates were left to rot, literally. One angry father wrote a letter about his daughter, then residing in Bethlem, who had been chained up and mistreated for so long that her foot was stinking and withered. Urbane Metcalf, in a pamphlet he published in 1818 called The Interior of Bethlem Hospital, complained ‘of the cruelties and abuses that are daily practised’ at Bethlem, including wet mattresses which were injurious to the health of all those sleeping on them, limited access to clean clothes, and the arbitrary use of corporal punishment and confinement to the basement.

The pits of Hell

The basement, even according to the most positive sources, was an appalling place. It was where the truly mad, raving, and dangerous were sent. Those who soiled themselves, were noisy, or violent, were placed there out of the way of the rest of the hospital, its patients, managers, and visitors. Patients were chained, rarely saw daylight, and were made to sleep on straw with no coverings. Those in charge considered the basement cells beyond their responsibility, and left the patients and their keepers to themselves. Ann Morley was admitted to Bethlem in October 1850 and spent just two months in the basement before she was discharged. Shortly afterwards, she was admitted to Northampton Lunatic Asylum where her new physician, Dr Nesbitt, found her in extremely poor physical health: Ann was skeletally thin and too weak to sit up, with a collapsed uterus and anus, semi-paralysed from the waist-down, unable to control bladder and bowel functions, and covered in marks and flea bites. When she was eventually able to talk again, for her time in Bethlem had rendered her mute, she told of the horrors of Bethlem. She had received a black eye on her first day from her keeper, Black Sall, and was chained, forced to sleep on the floor, and doused with freezing water, despite being obviously ill. Nesbitt took her story seriously and complained to the Lunacy Commission, whose subsequent report on the hospital was damning.

As seen, the basement was a den for sadistic keepers, who could use casual cruelty away from the prying eyes of those in charge. But even above stairs, keepers could be cruel. Between 1633 and 1700, over a third of male staff members mentioned in hospital records were dismissed for the likes of sexual abuse, violence, and theft. Urbane Metcalf wrote that ‘bribery is common to them all; cruelty is common to them all; villainy is common to them all; in short everything is common but virtue’. He told of instances where patients were beaten ‘so dreadfully for ten minutes as to leave [them] totally incapable of moving’, while other keepers kept watch for managers; where violent patients were encouraged by the keepers to attack others; and where chamber pots were emptied into shoes to have their victims sent to the basement. Urbane Metcalf, The Interior of Bethlem Hospital, London (1818). https://www.gethistory.co.uk/reference/sources/modern/georgian/the-interior-of-bethlem-hospital Even the ‘justifiable’ instances of abuse, such as the restraint of Norris, could be attributed to poor staffing: the incident that triggered the two stabbings was caused by a drunk keeper hitting Norris.

Urbane Metcalf, The Interior of Bethlem Hospital, London (1818). https://www.gethistory.co.uk/reference/sources/modern/georgian/the-interior-of-bethlem-hospital Even the ‘justifiable’ instances of abuse, such as the restraint of Norris, could be attributed to poor staffing: the incident that triggered the two stabbings was caused by a drunk keeper hitting Norris.

(Mis)treament

Many of the treatments used in Bethlem’s past today seem barbaric, as often they did to patients at the time. Sketches records one patient who was deeply troubled ‘to see any patient cupped, bled, leeched, or blistered; or indeed submitted to any necessary operation that gives pain. He invariably remonstrates, in his way, against such things; and afterwards condoles and sympathises with the poor infant, as he calls the patient. "They should not serve you so," says he, "'tis cruel; and I am sure you did not deserve it;" for he always imagines that such operations are inflicted as punishments, and he cannot be induced to think them of any benefit.’The rounds of treatments given to patients into the nineteenth century, even when they were elsewhere considered out-dated, were enough to turn the sane mad. These included blistering (where caustic compounds were put on the skin, often on a shaved head. This would cause blistering of the skin, which would lead to infection and the oozing of pus, which was considered a good thing as it released the problematic humours.), bleeding either by leeches or by scarification (where several cuts were made on the skin), and icy baths. Patients were given laxatives and emetics, as well as an array of other drugs to help them control their mood, their ‘humours’, and the chronic constipation they would often develop from long periods of inactivity.

Sketches records one patient who was deeply troubled ‘to see any patient cupped, bled, leeched, or blistered; or indeed submitted to any necessary operation that gives pain. He invariably remonstrates, in his way, against such things; and afterwards condoles and sympathises with the poor infant, as he calls the patient. "They should not serve you so," says he, "'tis cruel; and I am sure you did not deserve it;" for he always imagines that such operations are inflicted as punishments, and he cannot be induced to think them of any benefit.’The rounds of treatments given to patients into the nineteenth century, even when they were elsewhere considered out-dated, were enough to turn the sane mad. These included blistering (where caustic compounds were put on the skin, often on a shaved head. This would cause blistering of the skin, which would lead to infection and the oozing of pus, which was considered a good thing as it released the problematic humours.), bleeding either by leeches or by scarification (where several cuts were made on the skin), and icy baths. Patients were given laxatives and emetics, as well as an array of other drugs to help them control their mood, their ‘humours’, and the chronic constipation they would often develop from long periods of inactivity.

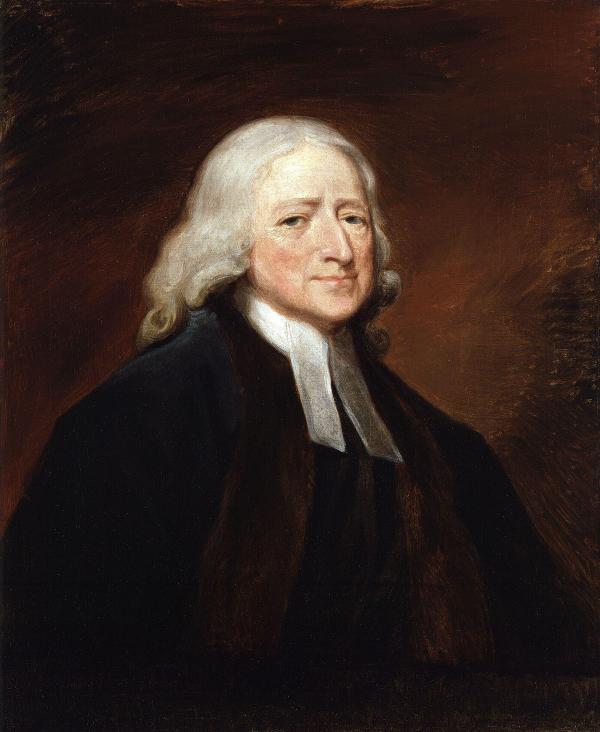

Thanks to the system of management often maintained at Bethlem, many of these treatments were prescribed with no examination of the patient and no knowledge of their case history. As the founder of Methodism, John Wesley, stated in the mid-eighteenth century, ‘They prescribe drug upon drug, without knowing a jot of the matter concerning the root of the disorder. And without knowing this they cannot cure, though they can murder, the patient.’ Quoted in Arnold, Bedlam, p.135 This seemed particularly true of Bethlem under the four generations of the Monro family, who were physicians-in-charge between 1728 and 1855. Wesley’s complaint arose from the story of Mrs Shaw and her son, Peter. Peter, suffering from an excess of religiosity, was sent to John Monro, who, without more than a cursory check of his health, confined him to a dark room and submitted him to a six-week regime of blood-letting and blistering, at the end of which Peter was unable to stand, but still mad. His mother wisely removed Peter from Monro’s care.

Quoted in Arnold, Bedlam, p.135 This seemed particularly true of Bethlem under the four generations of the Monro family, who were physicians-in-charge between 1728 and 1855. Wesley’s complaint arose from the story of Mrs Shaw and her son, Peter. Peter, suffering from an excess of religiosity, was sent to John Monro, who, without more than a cursory check of his health, confined him to a dark room and submitted him to a six-week regime of blood-letting and blistering, at the end of which Peter was unable to stand, but still mad. His mother wisely removed Peter from Monro’s care.

The report on the 1815 investigation, sparked by the scandals of Norris and York Asylum, roundly criticised Bethlem and so strongly expressed its disapproval of Thomas Monro that he resigned. He had spent almost no time at Bethlem, instead preferring to concentrate on his private, paying, patients. He never kept records, and so was unable to answer almost anything about any patient. He freely admitted to treating the rich and poor differently, for example stating that he would never put a gentleman in chains, but would advise restraining the lower orders whenever possible. He refused to give the patients any medicine in winter, as Bethlem was so cold that it would be a waste, and felt on the whole medicines were pointless as madness was incurable. Thomas Monro had attended George III during a bout of madness in 1811-12. His performance, however, was clearly not up to scratch, as Queen Charlotte ensured that he never treated the king again. Thirty years later little had changed when the 1852 report of the Lunacy Commission, which had been triggered by the treatment of Ann Morley, criticised Edward Monro for preferring the traditional approach of his ancestors over any founded on contemporarySomeone or something living or occurring at the same time.Someone or something living or occurring at the same time.Someone or something living or occurring at the same time. science. Like his father, he rarely visited, and knew nothing of the hospital or how it, or its staff, operated. He was found thoroughly incompetent, not just as physician-in-charge, but as a man of modern medicine. He never bothered to learn a patient’s case history, nor to find out what went on behind closed doors, and believed his duties extended no further than the occasional check on a few interesting patients. The wider response to the report was furious, The Lancet and the Journal of Psychological Medicine condemned him, the latter describing Bethlem as a place of ‘systematic cruelties, violence and neglect’ and the institution a ‘hideous exhibition of evil’.

Thomas Monro had attended George III during a bout of madness in 1811-12. His performance, however, was clearly not up to scratch, as Queen Charlotte ensured that he never treated the king again. Thirty years later little had changed when the 1852 report of the Lunacy Commission, which had been triggered by the treatment of Ann Morley, criticised Edward Monro for preferring the traditional approach of his ancestors over any founded on contemporarySomeone or something living or occurring at the same time.Someone or something living or occurring at the same time.Someone or something living or occurring at the same time. science. Like his father, he rarely visited, and knew nothing of the hospital or how it, or its staff, operated. He was found thoroughly incompetent, not just as physician-in-charge, but as a man of modern medicine. He never bothered to learn a patient’s case history, nor to find out what went on behind closed doors, and believed his duties extended no further than the occasional check on a few interesting patients. The wider response to the report was furious, The Lancet and the Journal of Psychological Medicine condemned him, the latter describing Bethlem as a place of ‘systematic cruelties, violence and neglect’ and the institution a ‘hideous exhibition of evil’. Quoted in Arnold, Bedlam, p.195

Quoted in Arnold, Bedlam, p.195

Managing madness

Sadly, management failings weren’t confined to the Monros, and since its foundation Bethlem has had a string of managers who weren’t just incompetent, but criminal as well. In 1403, Peter Taverner, the janitor placed in charge of the hospital, was found to have been pocketing charitable donations and selling the priory’s vestmentsRobes worn by the clergy. and ornaments as well as blankets and mattresses intended for patients. He opened the grounds to his cronies – vandals, thieves, tramps, and beggars who mutilated their own children - to share in his lifestyle and proceeds, and the priory became a den for drinking, gambling, and prostitution. In 1632 and 1633, Helkiah Crooke, who had formerly been James I’s physician, was found to have embezzled £100 per year of hospital funds, possibly to supplement his income from illegally selling hospital land. In 1835 Bethlem’s accountant fled for the Continent with £10,000 of the hospital’s money, shortly followed by Thomas Coles, the treasurer of Bethlem and Bridewell, who fled to Calais, leaving the institutions out of pocket by £14,000.

Despite the long list of management abuses, those with ultimate responsibility were loath to tackle Bethlem Hospital. Taverner, for example, was simply ordered to repay £100 of the roughly £300 he had stolen. Unable, or unwilling, to pay the fine, he left his job, and suffered no further punishment. Crooke was removed from Bethlem and resigned from the Royal College of Physicians, but avoided the sort of punishment that would be expected today: he was not charged with a crime, and is more likely to be remembered for his textbook on anatomy than for his neglect of the mentally ill. Despite being found lacking in almost every regard, Edward Monro was able to stay on at Bethlem as consulting physician for a further three years after the Lunacy Commission report.

Even where parliamentary investigations called for, and were granted, reform, Bethlem by-and-large managed to escape. It was exempted, for example, from the 1828 Madhouses Act, primarily because there were too many investors and interested parties in the House of Lords and the House of Commons. Nineteen of Bethlem’s governors sat in the CommonsPeople who weren't members of the clergy nor the nobility, or the House of Commons.People who weren't members of the clergyThe people ordained for religious duties, especially in the Christian Church. nor the nobilityThe highest hereditary stratum of the aristocracy, sitting immediately below the monarch in terms of blood and title; or the quality of being noble (virtuous, honourable, etc.) in character., or the House of Commons.People who weren't members of the clergy nor the nobility, or the House of Commons., and thirteen sat in the Lords. It also avoided inclusion under the 1845 Lunacy Act, and inspectors acting under it were refused permission to enter the hospital in 1848. With corruption at the top, it is hardly surprising it filtered down to managers and staff.

Nineteen of Bethlem’s governors sat in the CommonsPeople who weren't members of the clergy nor the nobility, or the House of Commons.People who weren't members of the clergyThe people ordained for religious duties, especially in the Christian Church. nor the nobilityThe highest hereditary stratum of the aristocracy, sitting immediately below the monarch in terms of blood and title; or the quality of being noble (virtuous, honourable, etc.) in character., or the House of Commons.People who weren't members of the clergy nor the nobility, or the House of Commons., and thirteen sat in the Lords. It also avoided inclusion under the 1845 Lunacy Act, and inspectors acting under it were refused permission to enter the hospital in 1848. With corruption at the top, it is hardly surprising it filtered down to managers and staff.

Yet not all managers of Bethlem were criminal or incompetent. Throughout Bethlem’s history, enlightened reformers have done what they could to improve the lives of their patients, and block others’ attempts to misuse them. The physician-in-charge in 1667, Thomas Allen, for example, prevented Robert Hooke from testing blood transfusions on patients. A ‘frantic’, Arthur Coga, was therefore recruited privately and paid 20s. Amazingly, he survived the procedure. Allen was less averse to experimenting on his patients once they were dead, and conducted autopsies to find the physical causes of madness. The first such recorded was in 1676, by Richard Wiseman, which discovered a brain tumour. When Edward Tyson

A ‘frantic’, Arthur Coga, was therefore recruited privately and paid 20s. Amazingly, he survived the procedure. Allen was less averse to experimenting on his patients once they were dead, and conducted autopsies to find the physical causes of madness. The first such recorded was in 1676, by Richard Wiseman, which discovered a brain tumour. When Edward Tyson Who was famous for his description of the anatomy of the orang-utan. took over from Allen in 1684, the hospital became so popular it developed a waiting list. The increase in popularity might have been due to Tyson’s insistence on treating the body as well as the mind, seeing to patients’ physical ailments, and providing nutritious food, hot baths and a level of after-care for those discharged. Robert Hale, who replaced Tyson after Tyson’s death in 1708, was also a compassionate man. He was a firm believer in the usefulness of conversation and company for patients, particularly those suffering from depression, and even recommended a hospital band, being an early proponent of music therapy. After the Monros’ fall from favour, William Hood became medical superintendent of Bethlem and under his care the building and regime received a face lift. He reduced the amount of restraint used, the iron bars were removed for non-acute patients and their straw mattresses were replaced with more comfortable ones. The library was enlarged, pictures appeared on the walls, and the grounds were rejuvenated. Patients were encouraged to work, read – there was even an in-house magazine printed - and socialise, with the chapel and the ballroom being put to their proper uses.

Who was famous for his description of the anatomy of the orang-utan. took over from Allen in 1684, the hospital became so popular it developed a waiting list. The increase in popularity might have been due to Tyson’s insistence on treating the body as well as the mind, seeing to patients’ physical ailments, and providing nutritious food, hot baths and a level of after-care for those discharged. Robert Hale, who replaced Tyson after Tyson’s death in 1708, was also a compassionate man. He was a firm believer in the usefulness of conversation and company for patients, particularly those suffering from depression, and even recommended a hospital band, being an early proponent of music therapy. After the Monros’ fall from favour, William Hood became medical superintendent of Bethlem and under his care the building and regime received a face lift. He reduced the amount of restraint used, the iron bars were removed for non-acute patients and their straw mattresses were replaced with more comfortable ones. The library was enlarged, pictures appeared on the walls, and the grounds were rejuvenated. Patients were encouraged to work, read – there was even an in-house magazine printed - and socialise, with the chapel and the ballroom being put to their proper uses.

Making an exhibition

So why the focus on the negative experiences of Bethlem, rather than the positives? Part of the problem must be down to the public’s love of the macabre and sensational stories: in general, the gossip and news that spreads the quickest is horrific or perverted. This even extends to restaurant reviews: Jay Reyner’s review of a terrible steakhouse for the Guardian in 2014 received over 28,000 shares, compared with just over 450 for his most recent positive review (correct as of 16 May 2017). https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/oct/30/negative-restaurant-review-bad-food-fun-read The stories that stick are the ones with rattling chains, insane moaning, and cruel and unusual punishment. Perhaps it’s also partly a result of Bethlem closing its doors to the inquisitive public. Without the ability to witness inside Bethlem’s walls, the public’s imagination could run wild. Perhaps, too, away from prying eyes the keepers had more opportunity to abuse their wards.

This even extends to restaurant reviews: Jay Reyner’s review of a terrible steakhouse for the Guardian in 2014 received over 28,000 shares, compared with just over 450 for his most recent positive review (correct as of 16 May 2017). https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/oct/30/negative-restaurant-review-bad-food-fun-read The stories that stick are the ones with rattling chains, insane moaning, and cruel and unusual punishment. Perhaps it’s also partly a result of Bethlem closing its doors to the inquisitive public. Without the ability to witness inside Bethlem’s walls, the public’s imagination could run wild. Perhaps, too, away from prying eyes the keepers had more opportunity to abuse their wards.

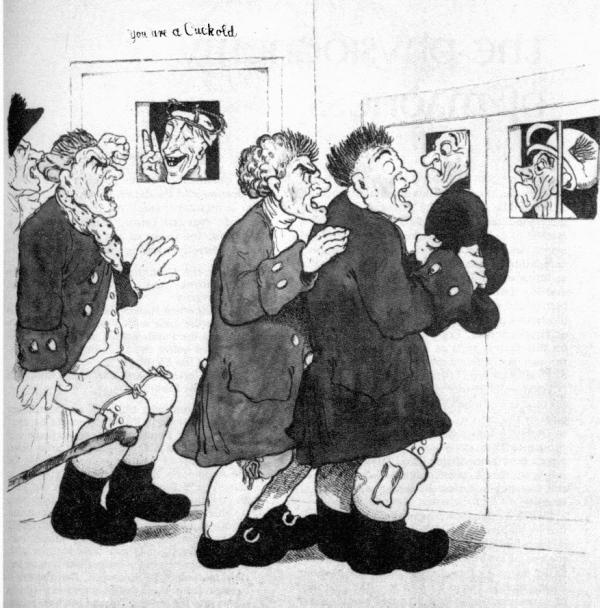

From the first paying visitor to Bethlem in 1610 until 1766 when the general public were locked out, Bethlem was a must-see for tourists, attracting as many as 100,000 visitors a year.  Roy Porter, ‘Being Mad in Georgian England’ History Today 31 (1981) They could wander through the galleries, talking to the patients, and providing them with money or food. Those visiting the hospital were expected to pay for it, and alms boxes were placed at the entrance. In this way, degrading though it was for at least some of the patients, the mass of tourists helped to sustain both the hospital and its patients: Catherine Arnold calculates that it provided about £400 a year in additional funds to the hospital.

Roy Porter, ‘Being Mad in Georgian England’ History Today 31 (1981) They could wander through the galleries, talking to the patients, and providing them with money or food. Those visiting the hospital were expected to pay for it, and alms boxes were placed at the entrance. In this way, degrading though it was for at least some of the patients, the mass of tourists helped to sustain both the hospital and its patients: Catherine Arnold calculates that it provided about £400 a year in additional funds to the hospital.

Not everyone approved of the tourist trade. Poet Abraham Cowley (1618-67) toured Bethlem several times and reported that ‘I returned not only melancholy, but sick with the sight.’ In 1695, Thomas Tyron, a founder of the vegetarian movement, requested that the hospital stop ‘admitting such Swarms of People, of all Ages and Degrees, for only a little paltry Profit to come in there, and with their noise, and vain questions to disturb the poor Souls; as especially such, as do Resort hither on Holy-dayes, and such spare time, when for several hours (almost all day long) they can never be at any quiet.’  Quoted in Arnold, Bedlam, pp.102-3 Inmates had to contend with continual taunting from their visitors and in the 17th century (unsuccessful) steps were taken to prevent the public from goading the patients, or providing them with strong liquor.

Quoted in Arnold, Bedlam, pp.102-3 Inmates had to contend with continual taunting from their visitors and in the 17th century (unsuccessful) steps were taken to prevent the public from goading the patients, or providing them with strong liquor.

Along with the tourists, all manner of ne’er-do-wells flocked to Bethlem. Pickpockets stole from unwary visitors, and robbed food and clothes from the patients. ‘Gentlemen’ would pick up ‘Mistresses…of all Ranks, Qualities, Colours, Prices and Sizes’, Ned Ward, The London Spy Compleat, London: J. How (1703) https://www.gethistory.co.uk/reference/sources/early-modern/stuart/the-london-spy-part-iii and stalls selling nuts, fruit, and cheesecake lined the walls. Scuffles and fights among the onlookers were frequent and, in May 1677, a riot broke out when one visitor offended others and accidentally stabbed a porter in the stomach. ‘Meanwhile, the inmates rattled their chains and battered on the doors of their cells for attention; or belted out a ballad in return for a glass of gin, with their fellow inmates roaring along with the choruses.’

Ned Ward, The London Spy Compleat, London: J. How (1703) https://www.gethistory.co.uk/reference/sources/early-modern/stuart/the-london-spy-part-iii and stalls selling nuts, fruit, and cheesecake lined the walls. Scuffles and fights among the onlookers were frequent and, in May 1677, a riot broke out when one visitor offended others and accidentally stabbed a porter in the stomach. ‘Meanwhile, the inmates rattled their chains and battered on the doors of their cells for attention; or belted out a ballad in return for a glass of gin, with their fellow inmates roaring along with the choruses.’ Arnold, Bedlam, p.97Their keepers, those paid to look out for their wards’ safety and well-being, instead paraded them around like animals at a circus. No wonder Bedlam became a by-word for uproar.

Arnold, Bedlam, p.97Their keepers, those paid to look out for their wards’ safety and well-being, instead paraded them around like animals at a circus. No wonder Bedlam became a by-word for uproar.

A retrospective

As with most things, the history of Bethlem is chequered. It was neither wholly bad, nor wholly good. Bethlem has gained its name partly through experience, fuelled by the public’s love of scandal, but partly because it was the first to attempt to care for the insane. Since 1247, it has provided shelter, comfort, and treatment to countless individuals. Caring staff have patiently and methodically looked after their patients’ physical, emotional, and intellectual needs, while far-sighted reformers have genuinely helped further the study of mental illness.

But to many, Bethlem has been a pit of misery and despair, offering nothing but a permanent end of the line. Cruel and twisted staff, together with apathetic management, have ruined countless lives, driving some sane mad, expediting the deaths of many, and making each day a hell to those in their ‘care’.

The attitudes of society, along with a good dollop of luck, seem to have been the major determiners of which experience this neglected, weak yet fearsome sub-section of society would have. For the insane are often reviled by a public fascinated with them: sometimes their maladies are just too close for comfort. While society disregards, fears, or belittles mental illness, sweeping it under the carpet, abuse will always continue. Bethlem was, is, and always will be, a product of its time.

Things to think about

- Why does Bethlem have its terrible reputation?

- Was Bethlem more a force for good, or for bad?

- Did Bethlem help anyone?

- What were the chances of leaving Bethlem cured?

- Who was the most to blame for the cases of cruelty and neglect?

- What can we learn from Bethlem about the state of medicine and society over the last 750 years?

- How have our attitudes towards the mentally ill changed?

Things to do

- Visit the Bethlem Museum of the Mind, which opened in 2015 and is situated in the grounds of the current Bethlem hospital. You can find out more information about it here.

- Visit the Imperial War Museum, which is based in a portion of what used to be the St Georges' Fields hospital. You can find out more information about it here.

- Search online for the considerable number of primary sources relating to Bethlem. Sketches can be found here, and The Interior of Bethlem Hospital can be found here.

Further reading

A fascinating read, which addresses the state of mental illness throughout history as well as the history of Bethlem is Catherine Arnold's Bedlam: London and its Mad.

Another colourful read is E.G. O'Donoghue's The Story of Bethlehem Hospital From its Foundation in 1247. O'Donoghue was the hospital's chaplain at the start of the twentieth century, as so has his own particular take on Bethlem and its history.

- Log in to post comments