Sir Walter Ralegh’s Weird and Wonderful ‘Discovery of Guiana'

When Sir Walter Ralegh visited South America in 1595, he fell in love with it – or at least in love with the idea of what it could do for him. After a clandestine marriage to one of Queen Elizabeth’s maids of honour, Bess Throckmorton, Ralegh had lost the queen’s favour and been thrown into the Tower of London as punishment. Although he was released from the Tower a few weeks later, he did not manage to recover the queen’s good graces, and would languish, banished from court, for many years to come. With a successful expedition to the fabled land of El Dorado, a land so rich that gold was everywhere freely available, Ralegh hoped at last to be able to come in from the cold, and to bask in Elizabeth’s high opinion once again.

Sadly, it was not to be. Despite reports from natives and Spaniards alike, Ralegh never reached the golden city of Manoa – not helped by the fact it didn’t actually exist. Instead he arrived back home in England comparatively empty-handed, with just a few samples of potential gold ore that in the end came to little. (Nor did he return with potatoes and tobacco, both legends that attached themselves to him later.) But this did not dampen his enthusiasm for the adventure. Assured that if he returned he would receive a ready welcome from the locals, who wanted to rid themselves of Spanish control, and that it was merely circumstance, a lack of preparation, and bad luck that had prevented him from reaching the golden capital city of Guiana, he determined to set off again quickly. But for this to succeed, he needed more backing, and money.

What was eventually published as Ralegh’s The Discoverie of the Large, Rich, and Bewtiful Empyre of Guiana was his attempt to attain just this. Initially, draft reports of his voyage had been sent to the queen and privy councilA monarch's private advisers. in manuscript form, promising the start of an empire of exotic lands rich in wonder and wealth, but no help was forthcoming. So, instead, Ralegh tried his luck with London sponsors, editing his text to make it more appealing to those with enough cash and imagination to chance an investment. In The Discoverie he carefully laid out the potential profits that could be made from gold mining as well as from the city itself, but he also couldn’t help occasionally waxing lyrical about everything he ‘discovered’ during his journey.

Debates have long been raging about the appropriateness and usefulness of Ralegh's descriptions of his travels, but this shouldn’t take away from the sense of wonder, fascination and sometimes-credulous inquiry that comes across when he speaks about the natives and their lives.

The possible

In the months he was in South America, travelling from the island of Trinidad along the Orinoco River to what would become Guyana City in modern-day Venezuela, Ralegh had considerable opportunity to observe the locals and their traditions. Although there was an element of bias – an attitude of European superiority over the ‘uncivilized’ natives – much that he recorded can be taken as coming close to an early-modern equivalent of an anthropological case study.

One group, the Trivitivas, whom Ralegh describes as ‘a verie goodlie people and verie valiant’, spent the time between May and September each year living in the trees, ‘where they build very artificiall [well-crafted] townes and villages’. This, Ralegh insists, is not because they were in any way savage – they have ‘the most manlie speech and most deliberate’ that he ever heard – but because ‘the river of Orenoke riseth thirtie foote upright, and then are those Ilands overflowen twentie foote high above the levell of the ground, saving some few raised grounds in the middle of them: and for this cause they are enforced to live in this maner.’ Joyce Lorimer (ed.), Sir Walter Ralegh’s Discoverie of Guiana (Aldershot: Hakluyt Society, 2006), p. 102.

Joyce Lorimer (ed.), Sir Walter Ralegh’s Discoverie of Guiana (Aldershot: Hakluyt Society, 2006), p. 102.

Ralegh explains how the different groups trade, and particularly how they traffic in humans with the Spanish, who

buie women and children from the Canibals,

In this instance, and most others, Ralegh uses the word 'cannibal' not to mean eaters of men, but to describe people who will destroy their own race and tribe for profit - selling people into slavery. His choice of words has been taken out of context on many occasions since. which are of that barbarous nature, as they will for 3. or 4. hatchets sell the sonnes and daughters of their owne brethren and sisters, and for somewhat more even their own daughters: hereof the Spaniards make great profit, for buying a maid of 12. or 13. yeeres for three or fower hatchets, they sell them againe at Marguerita in the west Indies for 50. and 100. pesos, which is so many crownes.

Ibid., pp. 83-5.

He describes the natives’ state of dress – or undress – and their diets and customs, including their love of alcohol. He notes ‘howe they beleeve the immortalitie of the Soule, [and] worship the Sunne’, and lists the various funerary rites: some ‘bury with them alive their best beloved wives and treasure … The Orenoqueponi bury not their wives with them, but their Jewels, hoping to injoy them againe. The Arwacas dry the bones of their Lordes, and their wives and friendes drinke them in powder.’ Ibid., p. 201.

Ibid., p. 201.

The weird and wonderful

All of the above, although tainted with the European outlook, is believable to a greater or lesser extent. Other descriptions seem a little less likely to be true. The Amazons, famed of Greek myth, are said to live ‘on the south side of the river in the Provinces of Topago’. These ‘cruell and bloodthirsty’ warrior women, who ‘accompanie with men but once in a yeere’, take a mate from a neighbouring tribe for a single month. During this time, they couple, ‘feast, daunce, & drinke of their wines in abundance’ in what sounds remarkably similar to a Bacchanalian rite. If a male child is the result of the pairing, it is returned to the father; if a female, then it is raised amongst the Amazons. With these alleged customs, the ancient myths of the elusive women seemed to be true (albeit on the other side of the world), apart from in one aspect: unlike in Greek legend, the women did not cut off their right breasts to improve their archery. Ibid., pp. 63-5.

Ibid., pp. 63-5.

Some historians have speculated that these mythical ‘Amazons’ do in fact have a basis in reality, perhaps inspired by matriarchal tribes in the area. But one tribe that can have very little grounding in fact is the headless Ewaipanoma. Ralegh describes these people as having ‘their eyes in their shoulders, and their mouths in the middle of their breasts, & that a long train of haire groweth backward betwen their shoulders.’ Furthermore, they were warriors of renown, being absolutely huge and using bows, arrows, and clubs three times the size of any normal weapon. Ibid., p. 157.

Ibid., p. 157.

Despite appearances, Ralegh was not all gullibility. Yes, he reported all the rumours he heard, and he tended to believe rather than doubt. But this was often done after rigorous – to the extent of his abilities – questioning. His reasoning was simple: although he was suspicious of many of the reports, they came from so many sources – including children – that they were, in effect, corroborated. Some stories fit well with the myths and legends of the ancients, but ultimately it was the spirit of the age that led him to accept. In the previous century the western world had changed. New places had been ‘discovered’, new thought patterns and beliefs had emerged, everything was changing. Was it really such a stretch, then, to allow that there could be other surprises out in the depths of a new continent? In the end, as Ralegh wrote, ‘whether it be true or no the matter is not great’ – it is the spirit of adventure that counts. Ibid.

Ibid.

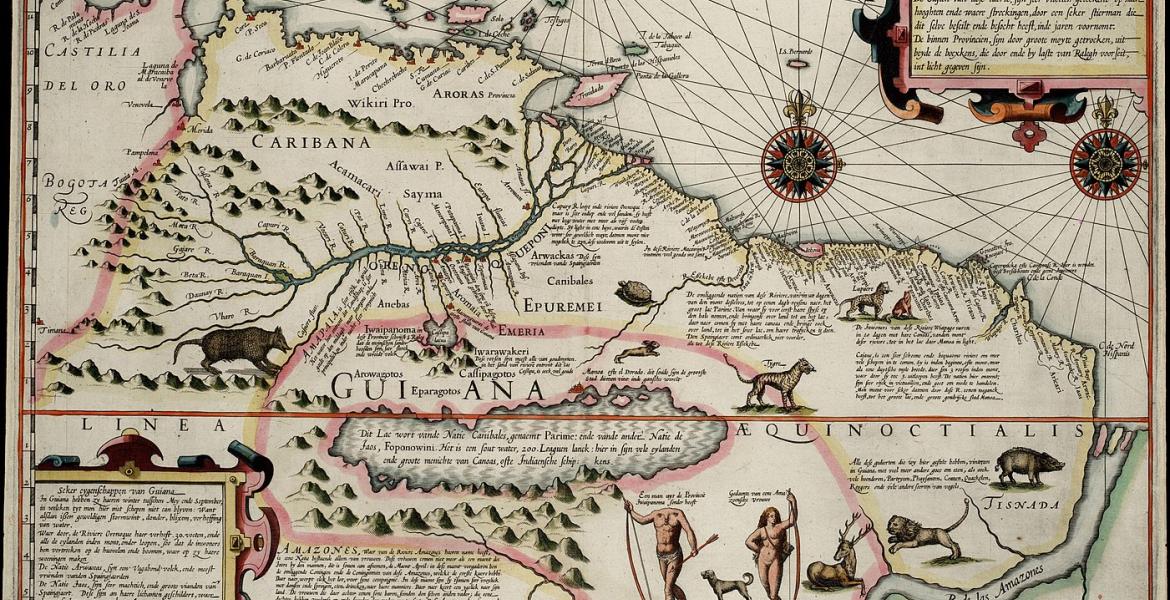

Cover image: Hondius's New Map of the Wonderful and Rich Land of Guiana (1599)

- Log in to post comments