Key points about the Great Storm of 1703

- The storm hit Britain on the night of 26 November 1703

- It caused considerable damage to buildings, trees, and goods

- Shipping and the Navy suffered heavily during the storm

- An estimated eight thousand people died during the storm, mainly at sea

- Many believed it happened because God was angry with the British people

People you need to know

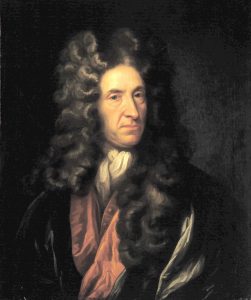

- Daniel Defoe – spy, journalist, author of several books including Robinson Crusoe, and witness to the Great Storm

On the night of 26 November 1703 (OS), what has been described as the worst storm in the history of the country hit Britain. Over the next eight hours, it reaped terrible damage across Wales and the south of England, before heading across the Channel and the North Sea towards Holland and Scandinavia. In its wake were thousands of trees blown down, fleets of ships destroyed, thousands of lives taken, and significant sums of money - in the form of goods, houses, churches, land and animals - washed away.

November had been a windy month, as storm upon storm crossed the Atlantic and caused problems across the country. A few days before the Great Storm, strong winds were said to have troubled the shores of America's eastern seaboard, from Florida up to Virginia. It is likely that this tropical storm picked up force as it headed across the Atlantic, where it began to be felt by the afternoon of Friday, 26 November.  To any with the instrumentation to observe it, it was clear a severe storm was blowing in. Daniel Defoe recorded that 'the Mercury sunk lower than ever I had observed it on any occasion whatsoever, which made me suppose the tube had been handled and disturbed by the children.'

To any with the instrumentation to observe it, it was clear a severe storm was blowing in. Daniel Defoe recorded that 'the Mercury sunk lower than ever I had observed it on any occasion whatsoever, which made me suppose the tube had been handled and disturbed by the children.'  Around midnight, the storm proper landed on the west coast of Wales, and moved at about 40kn towards the south and east, which it reached in the early hours of the following morning.

Around midnight, the storm proper landed on the west coast of Wales, and moved at about 40kn towards the south and east, which it reached in the early hours of the following morning.

At least two tornadoes were witnessed during, or immediately before, the storm. One, which appeared in Berkshire on 25 November, broke an oak tree and lifted a man off his feet. The man remained ill for some time, although the respondent, Joseph Ralton, attributed 'his illness more to the fright, than the sudden force with which he was struck down.' Another tornado, reported in Kent, lifted a boat 800ft from the water's edge onto dry land, and perhaps the same tornado was responsible for placing a cow high in the branches of a tree. The storm passed into the Channel, making its way toward Holland during the morning of 27 November, leaving a trail of destruction behind it.

The Great Storm on land

Across the country, thousands of trees, many hundreds of years old, fell. One estimate reckons that four thousand oaks were levelled in the New Forest alone and Defoe, who went on a tour of Kent following the storm, stopped counting fallen trees when he reached 17,000. Estates of the gentry were destroyed – 25 such with over a thousand trees down each, and 'above 450 parks and groves, who have from 200 large trees to 1,000 blown down in them'. John Evelyn lost two thousand on his Surrey estate. At one estate in Gloucestershire six hundred trees measuring 80ft high were torn down, 'so that the roots of most of the trees, with the turf and earth about them, stood up at least fifteen or sixteen foot high'. Orchards were also flattened. One respondent to Defoe said he feared there would be no cider available at all the next year and another from Somerset lamented that 'Our loss in the apple-trees is the greatest; because we shall want liquor to make our hearts merry'.

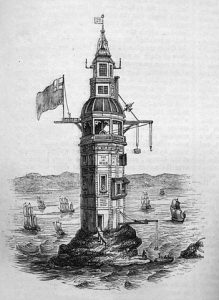

Trees were not the only things to fall. Over a hundred churches across the south of England had parts of their rooves ripped off, and many spires were damaged, some falling completely. In Kent, a steeple measuring upwards of 150ft 'was levelled with the ground, and made the sport and pastime of boys and girls, who to future ages, tho' perhaps incredibly, yet can boast they leaped over such a steeple'. In falling it damaged the church, and repairs cost between £800 and £1000. Houses likewise suffered: tiles flew off and chimneys fell in, sometimes bringing the floors down with them. An estimated two thousand chimneys in London were destroyed, and Defoe reckoned there were a thousand estates across the country that each had between five and twenty chimneys blown down. Buildings were destroyed in at least 35 separate places across the country, and those which weren't sturdily built suffered worse: reports abound of the poorer villagers having their houses completely uncovered, and barns, stables and other outbuildings across the country were flattened. In Kent alone, Defoe reckoned there were 1,107 'dwelling-houses, out-houses, and barns blown quite down'. Windmills were blown or burnt down, thanks to the friction generated by their spinning sails. Eddystone Lighthouse, the first recorded offshore lighthouse, was swept away. The six people in it, including its designer, Henry Winstanley, were never seen again.

The damage was so great that it led to a boom in the building and roofing trades: prices rose from 21s. per 1,000 plain tiles to £6, and from 50s. per 1,000 pantiles to £10, while the cost of thatch rose from 20s. to 50s. When prices returned to normal levels, it was not for lack of want, but because people couldn't afford them. Demand, and price, had been so high that 'an incredible number of houses remained all the winter uncovered, and exposed to all the inconveniences of wet and cold'. There also simply weren't enough tiles to go around: it was the wrong time of year to make more and many buildings including Christchurch Hospital and the Temple used temporary covers of wood or thatch to see them through until the next summer.

With so much damage to buildings, there was bound to be loss of life. According to the weekly bills, 21 people in London and about 123 across the country (excluding those drowned and not found) were killed as a result. Many deaths, such as the Bishop of Wells and his wife, were due to heavy chimneys falling in, squashing the occupants of houses as they slept below. Others were injured by flying debris: 'Whatever the danger was within doors, it was worse without. The bricks, tiles, and stones, from the tops of the houses, flew with such force, and so thick in the streets, that no one thought fit to venture out, though their houses were near demolished within.'

However, falling debris and chimneys were not responsible for the majority of deaths. The storm created a surge in the tidal rivers and along the coast, and all those on or near water were in danger. The River Severn rose 'eight foot higher than ever was known in the memory of man' and spread a mile out from its banks in Berkeley, Gloucestershire. Flooding was widespread around the Avon, Wye and Severn, where sheep and cattle drowned in whole flocks and herds. The land beneath was covered with salt, having a knock-on effect that would last several harvests. One respondent to Defoe wrote that 'The grass on the downs [near Lewes] was so salt, that the sheep in the morning would not feed till hunger compelled them, and afterwards drank like fishes'. The bridge over the Wye at Chepstow was partially washed away, as was a section of Cardiff's town wall. All those with goods in cellars along the waterways lost money: in Bristol, 1,000 hogsheads of sugar and 1,500 of tobacco were lost and it was reckoned that the damage done along the banks of the Severn cost over £200,000. Not only thousands of animals perished in the floods, but also people living near the waterways. In Bristol, several houses, many with residents in, were washed clean away, and those working to secure the goods of ships ran the risk of drowning or being crushed.

The Great Storm at sea

But it was those on the boats who suffered the most, and it is this loss of life for which the Great Storm is primarily remembered. The harbours of Britain were busy when the storm hit. The War of the Spanish Succession was underway, and the British fleet was at the ready, anchored around the coast. The Russian fleet of almost one hundred ships was near the British coast as the winds increased and was dispersed by its power, with some ships going 'into Newcastle, some into Hull, and some into Yarmouth roads; two foundered in the sea; one or two more run ashore, and were lost; and the reserve frigate, their convoy, foundered in Yarmouth roads, all her men being lost'. To this crowd were added the merchant vessels. With high winds during the first part of November, many British ships remained in port, and others were chased in. Those sailing from the Americas made good, if uncomfortable, time, yet could not make the return journey for the strength of the oncoming wind. Those that did venture out into open sea soon found themselves pushed backwards, and many boats decided not to attempt leaving the harbour at all.

When the Great Storm swept in on 26 November, it found a chaos of boats that were easy pickings. Despite the best efforts of their men, many broke anchor and were driven into others, with both foundering. Others were driven out into the open sea, often with their masts cut, where they were completely at the mercy of the elements. One tin ship operating near Helford in Cornwall was blown from her anchors and ended, eight hours later, wrecked on the Isle of Wight. Although the ship was lost, the goods and men on board were saved.

The Paris Gazetteer reported that eighty thousand sailors and three hundred ships were lost, which was without doubt an exaggeration – although apparently a believable one. Closer estimates reckon that about eight thousand died at sea or due to drowning during the storm, although an exact figure will never be possible to achieve. Ships were wrecked as far apart as the south coast of England, the Bristol Channel, Wales, the Humber and Holland. It is estimated that one-third of all seamen in the Navy, some ten thousand men, were lost on the night of the storm.  Thomas Short, writing in 1749, thought that 'England lost more ships in this storm than ever were lost in any encounter with an enemy'.

Thomas Short, writing in 1749, thought that 'England lost more ships in this storm than ever were lost in any encounter with an enemy'.  One seaman described the horror of the night:

One seaman described the horror of the night:

By two a-clock we could hear guns firing in several parts of this road, as signals of distress; and tho' the noise was very great with the sea and wind, yet we could distinguish plainly, in some short intervals, the cries of poor souls in extremities… It was a sight full of terrible particulars, to see a ship of eighty guns and about six hundred men in that dismal case; she had cut away all her masts, the men were all in the confusions of death and despair; she had neither anchor, nor cable, nor boat to help her; the sea breaking over her in a terrible manner, that sometimes she seem'd all under water; and they knew, as well as we that saw her, that they drove by the tempest directly for the Goodwin, where they could expect nothing but destruction. The cries of the men, and the firing their guns, one by one, every half minute for help, terrified us in such a manner, that I think we were half dead with the horror of it.

Many of the Navy, being anchored at the Downs off the Kentish coast, were driven onto the Goodwin Sands.  Survivors from the wrecked boats collected on the sandbanks, which are above water at low tide, and 'Here they had a few hours' reprieve, but had neither present refreshment, nor any hopes of life, for they were sure to be all washed into another world at the reflux of the tide. Some boats are said to come very near them in quest of booty, and in search of plunder, and to carry off what they could get, but nobody concerned themselves for the lives of these miserable creatures.' One who narrowly avoided such a fate, writing aboard HMS Shrewsbury said that:

Survivors from the wrecked boats collected on the sandbanks, which are above water at low tide, and 'Here they had a few hours' reprieve, but had neither present refreshment, nor any hopes of life, for they were sure to be all washed into another world at the reflux of the tide. Some boats are said to come very near them in quest of booty, and in search of plunder, and to carry off what they could get, but nobody concerned themselves for the lives of these miserable creatures.' One who narrowly avoided such a fate, writing aboard HMS Shrewsbury said that:

Sir, — These lines I hope in God will find you in good health; we are all left here in a dismal condition, expecting every moment to be all drowned: for here is a great storm, and is very likely to continue; we have here the rear admiral of the blew in the ship call'd the Mary, a third rate, the very next ship to ours, sunk, with Admiral Beaumont, and above 500 men drowned: the ship call'd the Northumberland, a third rate, about 500 men all sunk and drowned: the ship call'd the Sterling castle, a third rate, all sunk and drowned above 500 souls: and the ship call'd the Restoration, a third rate, all sunk and drowned: these ships were all close by us which I saw; these ships fired their guns all night and day long, poor souls, for help, but the storm being so fierce and raging, could have none to save them: the ship called the Shrewsberry, that we are in, broke two anchors, and did run mighty fierce backwards, with 60 or 80 yards of the sands, and as God Almighty would have it, we flung our sheet anchor down, which is the biggest, and so stopt: here we all pray'd to God to forgive us our sins, and to save us, or else to receive us into his heavenly kingdom. If our sheet anchor had given way, we had been all drown'd: but I humbly thank God, it was his gracious mercy that saved us. There's one, Captain Fanel's ship, three hospital ships, all split, some sunk, and most of the men drown'd.

There are above 40 merchant ships cast away and sunk: to see Admiral Beaumont, that was next us, and all the rest of his men, how they climbed up the main mast, hundreds at a time crying out for help, and thinking to save their lives and in the twinkling of an eye, were drown'd: I can give you no account, but of these four men-of-war aforesaid, which I saw with my own eyes, and those hospital ships, at present, by reason the storm hath drove us far distant from one another: Captain Crow, of our ship, believes we have lost several more ships of war, by reason we see so few; we lye here in great danger, and waiting for a north-easterly wind to bring us to Portsmouth, and it is our prayers to God for it; for we know not how soon this storm may arise, and cut us all off, for it is a dismal place to anchor in. I have not had my cloaths off, nor a wink of sleep these four nights, and have got my death with cold almost.

Yours to command.

Miles Nobcliffe.

I send this, having opportunity by our botes, that went ashore to carry some poor men off, that were almost dead, and were taken up swimming.

The residents of Deal, not ten miles away, were heavily criticised for their refusal to help these men. Only one man, Thomas Powell the mayor of the town, was able to rouse some support, by offering to pay 5s. a head to any who helped, and stealing the uncooperative customs officers' boats. Rescuing two hundred men, he fed, clothed and found lodgings for them, all at his own expense. Despite his ministrations, many did not survive the night. He buried the dead and the rest he furnished with enough money to reach Gravesend, again out of his own pocket. Defoe goes on to lament that 'I wish I could say with the same freedom, that he received the thanks of the Government, and reimbursement of his money as he deserved, but in this I have been informed, he met with great obstructions and delays, though at last, after long attendance, upon a right application, I am informed, he obtained the repayment of his money, and some small allowance for his time spent in soliciting for it'.

Unwillingness to help others wasn't limited to government officials and the residents of Deal. 'A gang of hardened rogues assaulted a family at Poplar, in the very height of the storm, broke into the house, and robbed them: it is observable, that the people cried thieves, and after that cried fire, in hopes to raise the neighbourhood, and to get some assistance; but such is the power of self-preservation, and such was the fear the minds of the people were possessed with, that nobody would venture out to the assistance of the distressed family, who were rifled and plundered in the middle of all the extremity of the tempest.' Nor did pregnant women fare better. 'Several women in the city of London who were in travail, or who fell into travail by the fright of the storm, were obliged to run the risk of being delivered with such help as they had; and midwives found their own lives in such danger, that few of them thought themselves obliged to shew any concern for the lives of others.'

Aftermath and legacy

The scale of the damage, and the amount of lives lost, led to a searching among the survivors for a reason for the storm. A favoured explanation was that it was 'the dreadest and most universal judgment that ever almighty power thought fit to bring upon this part of the world.' The storm was a punishment from God, visited on England for its sins, for atheism and turning away from the correct Christian path. Queen Anne's government agreed, announcing that the calamity 'loudly calls for the deepest and most solemn humiliation of our people' and proclaiming a national day of fasting on 5 December in recognition of the 'crying sins of this nation'. The motion of the wind was little understood at the beginning of the eighteenth century, seeming 'to be more of God in the whole appearance, than in any other part of operating nature.' Wind, according to Defoe, was God's remaining mystery, so it was only fitting that it be used to punish a place that had become infested with atheists and sinners.

The motion of the wind was little understood at the beginning of the eighteenth century, seeming 'to be more of God in the whole appearance, than in any other part of operating nature.' Wind, according to Defoe, was God's remaining mystery, so it was only fitting that it be used to punish a place that had become infested with atheists and sinners.

Given the range and damage of the storm, there is no doubting its significance, but was it really the biggest storm Britain has witnessed in recorded history? Defoe called it 'the greatest, the longest in duration, the widest in extent, of all the tempests and storms that history gives any account of since the beginning of time.' Yet Hubert Lamb, who undertook a huge survey of British storms placed it fifth in his list. Admittedly, many of the others – such as the storm of 1987, as well as those of 1825 and 1792 – came after the Great Storm, but he also lists one that happened just nine years before it. There was objective proof available at the time that some aspects of the storm were not as bad as previous weather, and that atmospheric pressure, as measured through barometer readings, was just as low two weeks before 26 November.  An unfortunate combination of circumstances, particularly at sea, undoubtedly increased the effects of the storm. Yet the anonymous author of An Exact Relation of the Late Dreadful Tempest, published in 1704, stated that some of the early reports of damage and loss of life on the sea were not as bad as first supposed, as more men and ships made their way back to England. Others pointed to the fall in the price of grain that winter as an indication that damage to crops was not as great as feared.

An unfortunate combination of circumstances, particularly at sea, undoubtedly increased the effects of the storm. Yet the anonymous author of An Exact Relation of the Late Dreadful Tempest, published in 1704, stated that some of the early reports of damage and loss of life on the sea were not as bad as first supposed, as more men and ships made their way back to England. Others pointed to the fall in the price of grain that winter as an indication that damage to crops was not as great as feared.

Part of the storm's fame comes from the records that were published subsequently, particularly Daniel Defoe's, which kept it in people's minds and which told so many stories of suffering. After surveying the damage done by the storm to London's shipping, Defoe felt inspired to post an advertisement in the London Gazette asking for eye witnesses. He received a considerable response from across the country and compiled a book called The Storm: or, a Collection of the most Remarkable Casualties and Disasters which happened in the late Dreadful Tempest, both by Sea and Land. This work has been called the first substantial work of modern journalism, but his intention wasn't simply to inform: it was to spread the message he read in the storm. 'The main inference I shall pretend to make or at least venture the exposing to public view, in this case, is, the strong evidence God has been pleased to give in this terrible manner to his own being, which mankind began more than ever to affront and despise'.

Defoe's book, gripping and well-researched as it may be, inclines toward exaggeration. He describes the impact of the storm as 'universal, and its extent general, not a house, not a family that had anything to lose, but have lost something by the storm, the sea, the land, the houses, the churches, the corn, the trees, the rivers, all have felt the fury of the winds.' Yet in places such as Hastings, we hear the total damage did not exceed £40, and others like Swansea felt nothing more than was commonly experienced during storms. Of course, some places were hit harder than others but for every animal drowned, many others escaped unharmed, and for every death reported, many more wrote of their miraculous survival.

Whatever the true nature of the storm itself, the sweeping impact it had on many lives, livelihoods, and minds cannot be ignored. And it is for this reason that the storm of 1703 will always be remembered as the Great Storm.

Things to think about

- How great a storm was it?

- What do the reasons given for the storm tell us about society and religious belief at the start of the eighteenth century?

- How much does fear have an impact on the experience and recording of the storm?

- How have improvements in scientific knowledge helped us to understand storms, and how has this affected us culturally?

Things to do

- For those brave enough, it is possible to visit Goodwin Sands at low tide. Information on trips can be found here.

- Look at experiences of the Great Storm, as recorded by the likes of Defoe, and compare them with records from later storms. What does this tell you about the impact of the storm?

Further reading

Essential reading for anyone interested in the Great Storm of 1703 is Daniel Defoe's The Storm: or, a Collection of the most Remarkable Casualties and Disasters which happened in the late Dreadful Tempest, both by Sea and Land.