Ten Facts You Might Not Know about Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys is best known for his diary, which he kept from 1660 until 1669, when he gave it up over fears of his eyesight failing. As such, his views are often quoted over the RestorationThe restoration of the monarchy and the return to a pre-civil war form of government in 1660, following the collapse of the Protectorate., the plague, the Great Fire of London, and the Chatham Raid. All of these are very exciting episodes, and deserve attention, but, as you can find out below, there is so much more to Pepys than these set pieces.

Pepys was a fashionista.

He was one of the first in England to adopt the periwig, recording in his diary how he let his barber shear his hair so he could wear this strange new fashion accessory. Periwigs were so new that Pepys was concerned how his new hairstyle would be received (by everyone but his wife). One of his wigs was, in fact, made from his own hair, although others came from hair provided by people who were so poor that they had to sell their hair. Later, during the plague of 1665, he worried that the hair used for the wigs might be taken from the plague dead, and wisely decided not to buy any more for the duration.

He was integral to the reform of the navy.

Despite having had very little to do with the sea before the Restoration, upon the return of Charles II he was given a place on the Navy Board, which was responsible for the day-to-day civil administration of the Royal Navy. He went about learning his new job with his usual gusto, and suggested a number of essential changes that were implemented and remained in place for over a century. Some of the most important of his reforms included a centralised victuallingProviding with food or other stores. structure, a professional test for officers, and a pay structure that ensured officers received continuous pay and a pension. Pepys did, of course, make sure he would be well-rewarded for suggesting these reforms: he was put in charge of overseeing the new system.

Pepys was aboard the ship that returned Charles II from exile.

The ship on which the king returned had departed Britain as the Naseby(after the battle that saw a resounding parliamentarianA supporter of parliament, particularly during the Civil Wars of 1642-1651. victory over the royalists), but was renamed to the Royall Charles and done up – including removing the Oliver Cromwell figurehead – to make it more amenable to the royal passenger. Pepys recorded in his Diary his first impressions of the royal family: how Charles ‘fell into discourse of his escape from Worcester, where it made me ready to weep to hear the stories that he told of his difficulties’; how the duke of York ‘called me Pepys by name, and upon my desire did promise me his future favour’; and how in the barge that returned Pepys to shore, one of the king’s dogs defecated in the boat, ‘which made us laugh, and me think that a King and all that belong to him are but just as others are’. Diary, 23 May 1660; 25 May 1660.

Diary, 23 May 1660; 25 May 1660.

He was implicated in the Popish Plot and spent time in prison as a result.

Despite having had a puritanDescribing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism. upbringing, taking the oath required by the Test Act, and attending Anglican ceremonies, his association with the Catholic duke of York (later James II) made him an easy target. He was accused of being a Catholic, of having organised the death of a magistrate investigating the Plot, and of having sold naval secrets to the French. After a stint in the Tower, he was released on bail, For £30,000, almost £5 million today. He had to find £10,000 himself; the rest was provided by his obliging friends. and set about proving his innocence. He had friends and relatives scour the continent to find evidence against the supposed witnesses – a fraudster known as Colonel John Scott, and his ex-butler John James (who had been sacked after being caught in flagrante with the housekeeper) – bringing their own witnesses to England and recording a deathbed confession from John James that he had been bribed by certain prominent parliamentariansPeople supporting parliament in the civil wars; or members of parliament, particularly those who are knowledgeable about politics. to bear false witness. Almost a year after being bailed, the case against Pepys was dropped in June 1680.

For £30,000, almost £5 million today. He had to find £10,000 himself; the rest was provided by his obliging friends. and set about proving his innocence. He had friends and relatives scour the continent to find evidence against the supposed witnesses – a fraudster known as Colonel John Scott, and his ex-butler John James (who had been sacked after being caught in flagrante with the housekeeper) – bringing their own witnesses to England and recording a deathbed confession from John James that he had been bribed by certain prominent parliamentariansPeople supporting parliament in the civil wars; or members of parliament, particularly those who are knowledgeable about politics. to bear false witness. Almost a year after being bailed, the case against Pepys was dropped in June 1680.

He had an operation for the ‘stone’.

From a young age, Pepys had suffered from kidney stones that were so bad that, in 1658, he had an operation to remove them. He legs were tied up close to his shoulders, then he was shaved and held down by strong men. The surgeon inserted an instrument through his urethra to position the stone in the bladder before making a three-inch-long incision between his scrotum and anus. The stone was then found and removed by pincers inserted in the wound, which was then allowed to heal naturally – without stitches. The stone was over two inches across and had been removed without the aid of any painkillers: anaesthetics had not been invented, and alcohol could not be used as the surgery was on the bladder. He kept the stone in a specially made case, and vowed to celebrate the anniversary of the operation every year with a dinner.

Pepys was the one to inform Charles II about the Great Fire of London.

After witnessing the destructiveness of the Fire and noticing that ‘nobody, to my sight, [was] endeavouring to quench it’, Pepys went to Whitehall, ‘to the King’s closet in the chapel … and did tell the King and the Duke of York what I saw, and that unless his Majesty did command houses to be pulled down, nothing could stop the fire.’ Following his report, Charles instructed Pepys to find the Lord Mayor and ‘command him to spare no houses, but to pull down before the fire every way’, while the duke of York offered soldiers to help. Diary, 2 September 1666. It was to no avail: the Fire was to rage for another four days, driven by strong winds and helped by dry weather.

Diary, 2 September 1666. It was to no avail: the Fire was to rage for another four days, driven by strong winds and helped by dry weather.

The republicanSomeone who believes power should belong to the people; someone who doesn't support a monarchy. boy who witnessed and approved of the execution of Charles I willingly gave up his career to support Charles I’s son, the Catholic James II.

This is despite having a rather poor opinion of the Restoration monarchyThe king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head. privately: he wrote about the ‘silliness’ of Charles II and how, instead of taking the business of state seriously, at meetings Charles spent his time ‘playing with his dog all the while, or his codpiece’. Diary, 7 February 1669. He became a nonjuror (refusing to swear an oath to the new king, because he had sworn an oath to the usurpedTo have taken a (person's) position of power or importance illegally or by force. king) and had to leave his job at the Admiralty. In 1689 and 1690 he was arrested under suspicion of treasonable activities and of being a Jacobite, and both times he was released on bail. At least part of the bail money came from two very rich and notable friends: Robert Blackborne, secretary to the East India CompanyA monopolistic company formed to engage in trade with Southeast Asia and India., and James Houblon, one of the first board members of the Bank of England.

Diary, 7 February 1669. He became a nonjuror (refusing to swear an oath to the new king, because he had sworn an oath to the usurpedTo have taken a (person's) position of power or importance illegally or by force. king) and had to leave his job at the Admiralty. In 1689 and 1690 he was arrested under suspicion of treasonable activities and of being a Jacobite, and both times he was released on bail. At least part of the bail money came from two very rich and notable friends: Robert Blackborne, secretary to the East India CompanyA monopolistic company formed to engage in trade with Southeast Asia and India., and James Houblon, one of the first board members of the Bank of England.

Pepys and his friends were robbed by highwaymen.

Pepys’s coach was particularly garish: it was painted with seascapes and naval scenes, and this might have been what attracted attention from the wrong sort. One man put a pistol to Pepys’s head as Pepys handed over a bag containing about £3, his silver ruler, his gold pencil, five mathematical instruments, and a magnifying glass; Pepys’s mistress, Mary Skinner, had enough wits about her to hide her own money bag beneath her skirts. A gentleman’s agreement was made that the pencil would be returned to Pepys the following day, at the Rummer Tavern in Charing Cross. Unsurprisingly, the highwaymen did not appear, but were later discovered there in possession of the pencil. Thomas Hoyle and Samuel Gibbons were tried at the Old Bailey two months, where Pepys claimed the pencil but refused to swear to their identities, having not seen their faces during the robbery. Nevertheless, they were found guilty of felony and robbery, and were condemned to death. ‘December 1693, trial of Thomas Hoyle, Samuel Gibbons’ (t16931206-24), at Old Bailey Proceedings Online, <www.oldbaileyonline.org>, accessed 18 September 2019.

‘December 1693, trial of Thomas Hoyle, Samuel Gibbons’ (t16931206-24), at Old Bailey Proceedings Online, <www.oldbaileyonline.org>, accessed 18 September 2019.

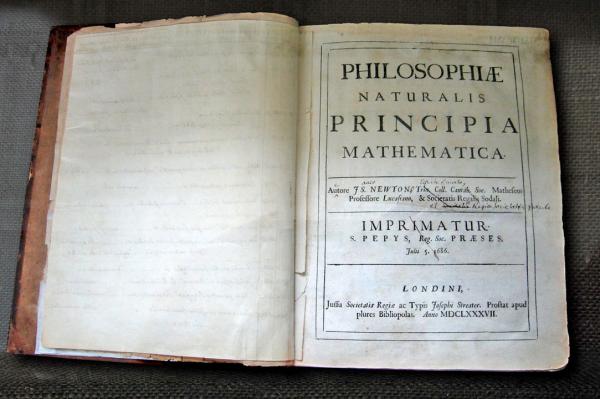

Pepys’s name appears on the title page of Newton’s Principia Mathematica.

Pepys had joined the Royal Society in 1665, just three years after it received its royal charter, and in 1684 became its president. It is through this role that his name will forever be linked to Newton’s ground-breaking work. Pepys was not chosen as president because of any great understanding of the sciences – in fact he struggled with many of Newton's and Boyle’s works – but because he was such an effective administrator.

After his death, Pepys’s body was autopsied.

It was conducted by fellow members of the Royal Society Hans Sloane and Charles Bernard at the request of Pepys’s nephew, John Jackson. The results gave an indication of exactly what pain Pepys must have been suffering under in his last months: his left kidney was full of stones, his gut inflamed and septic, his bladder gangrenous and the old surgical wound reopened, and his lungs full of black spots and foam. His heart and right kidney, however, appeared healthy.

- Log in to post comments