The sinking of an unsinkable ship: Titanic

Key points about Titanic

- Titanic was the largest ship of her day, known for luxury and splendour.

- She hit an iceberg four days into her maiden voyage and sank on 15 April 1912.

- Most of her passengers and crew died in the disaster.

- There were a number of reasons for the disaster, including too few lifeboats and a lack of safety precautions.

People you need to know

- Thomas Andrews - designer of Titanic, who died during the disaster.

- John Jacob Astor IV - wealthy American businessman and great-grandson of America's first multimillionaire who died on Titanic.

- Frederick Fleet - lookout in the crow's nest on the night Titanic hit the iceberg. He survived the disaster, but hanged himself in 1965.

- Benjamin Guggenheim - wealthy American businessman and son of a mining tycoon, who died when Titanic sank.

- J. Bruce Ismay - managing director of the White Star Line, who escaped from the sinking Titanic.

- William Murdoch - first officer on Titanic, who died during the disaster.

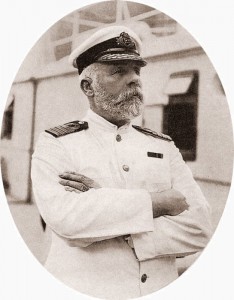

- Edward Smith - captain of Titanic, who died during the disaster.

- Isidor Straus - German-born American businessman and co-owner of Macy's department store, who died on Titanic.

Titanic is one of the most famous shipwrecks in the world. Its story has captured imaginations and sunk into our popular culture, featuring in films, programmes, the theatre, computer games and books. All of these have contributed to our general knowledge of the events of the night of 14-15 April 1912, when the ship hit an iceberg below the waterline and sank, taking most of her 2,000-odd passengers and crew to a watery grave over two miles beneath the surface. But as well as adding to the myths and mystique surrounding the disaster, these films have confused facts that were often not particularly clear in the first place - even the initial enquiries into the disaster couldn't agree on the numbers killed. Cameron's 1997 film Titanic is a case in point, with known events changed to reflect the concerns of the audience. As maritimeConnected with the sea, especially in relation to seaborne trade or naval matters. historian Sam Willis has rightly said, 'a budget of $200 million buys a lot of collective memory'. Sam Willis, Shipwreck: A History of Disasters at Sea (London: Quercus Editions, 2008), p.198.

Sam Willis, Shipwreck: A History of Disasters at Sea (London: Quercus Editions, 2008), p.198.

Although Titanic stood out for being the largest ship afloat at the time, it was not the only shipwreck of the era, and nor was it the worst. When the German ship, the Wilhelm Gustloff, was torpedoed by a Russian submarine in 1945, more than 9,000 injured soldiers and civilian refugees were killed - about four times the death toll of Titanic. So what is it about this particular disaster that attracts us so much? There is the morbid fascination that makes us crane our necks as we go past road accidents, but also the tales of heroism and chivalryA knightly code of correct social, religious and moral behaviour., and the scientific interest that makes one wonder how an 'unsinkable' ship could, indeed, sink on her maiden voyage. Behaviour on board Titanic has been favourably contrasted with that on board other wrecks, such as the French warship Droits de l'Homme which sank in 1797 and whose lifeboat capsized in the mad rush of individuals to save themselves. Perhaps, then, Titanic stands out as being an example of how people should behave when disaster hits; it certainly makes a refreshing change from the pessimism found across the media, from zombie films to modern politics. Other, deeper, reasons have been suggested for our continuing interest: that she was a model of society at large, or that she represented the 'greatness' of Britain. As far as analogies go, it's not a bad one.

Titanic was first conceived by the White Star Line in 1907 to be the height of luxury and splendour, and the project was encouraged by the line's managing director, J. Bruce Ismay. Ismay was the highest ranking White Star official to make it off the ship and was one of the witnesses in the enquiries. A reasonable amount of controversy surrounds his lucky escape, with many claiming he acted dishonourably in putting his own life above those of the women and children still aboard. Society labelled him a coward and he lived out his life in relative isolation. She was built in Belfast and then taken to Southampton, where she set off on her maiden voyage on 10 April 1912. A transatlantic steam ship, she stopped first at Cherbourg in France and then Queenstown (now Cobh) in Ireland, before embarking on the main portion of her journey to New York. By this point, between 2,201 and 2,223 passengers and crew were on board.

Ismay was the highest ranking White Star official to make it off the ship and was one of the witnesses in the enquiries. A reasonable amount of controversy surrounds his lucky escape, with many claiming he acted dishonourably in putting his own life above those of the women and children still aboard. Society labelled him a coward and he lived out his life in relative isolation. She was built in Belfast and then taken to Southampton, where she set off on her maiden voyage on 10 April 1912. A transatlantic steam ship, she stopped first at Cherbourg in France and then Queenstown (now Cobh) in Ireland, before embarking on the main portion of her journey to New York. By this point, between 2,201 and 2,223 passengers and crew were on board. The exact numbers vary depending on which report – British or American – one reads. Of these, between 885 and 899 were crew.

The exact numbers vary depending on which report – British or American – one reads. Of these, between 885 and 899 were crew.

The route itself was not unusual: hundreds of similar journeys were made every year by a number of companies, including the White Star Line and Cunard. Nor was her speed unusual: companies and ships often competed for the Blue Riband, which was awarded to the ship that made the fastest transatlantic crossing. In fact, the designers of Titanic were much more concerned about her splendour than her speed, seeing the Blue Riband award as a little crass. They wanted Titanic to be remembered for her luxury, and for providing the best accommodation available: Titanic's à la carte restaurant was designed as a Louis XIV banqueting hall and the walls of the first class smoking room were panelled in mahogany.

While her luxury attracted the likes of wealthy businessmen Benjamin Guggenheim, John Jacob Astor IV, and Isidor Straus, she wasn't just a ship for the rich. There were also hundreds of passengers from the lower rungs of society, travelling in second or third class, many of whom were emigrating to the United States. But the most dangerous thing travelling in her, according to new research by Senan Molony, was a fire in her hull that had been raging for up to three weeks at temperatures of up to 1000°C. Molony believes that this fire, which was known about by the crew but kept secret from the passengers, fundamentally weakened the integrity of the hull by up to 75%, making any collision extremely hazardous.

Seemingly under pressure to make the crossing within six days, either to win the Blue Riband or to dock to cope with the fire, Titanic's captain steadily increased her speed during her journey – despite iceberg warnings - and by the night of 14 April, she had reached a speed of 21.5 knots. The ship Californian, who didn't come to her aid, had stopped nearby because of the risk of icebergs, and had attempted to warn Titanic of the risk as well.< This, the captain claimed, was normal practice even under hazardous conditions, as it was assumed that any iceberg big enough to sink a ship would be seen in time to avoid collision.

The ship Californian, who didn't come to her aid, had stopped nearby because of the risk of icebergs, and had attempted to warn Titanic of the risk as well.< This, the captain claimed, was normal practice even under hazardous conditions, as it was assumed that any iceberg big enough to sink a ship would be seen in time to avoid collision.

The assumption was wrong. RMS Titanic hit an iceberg off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland at 11:40pm on 14 April 1912. The iceberg was first spotted by the crow's nest lookout Frederick Fleet, who immediately signalled a collision course and spoke with the bridge via telephone to warn them. First officer William Murdoch ordered the helm turned hard astarboard. But it was too late: the unusually calm water had stopped the iceberg from being seen in time for the ship to turn, and it struck below the waterline in several places along the starboard side. After taking a tour of the damaged parts of the ship, Titanic's designer, Thomas Andrews, informed Captain Edward Smith that the unsinkable ship would, in fact, sink. Within 40 minutes of the collision, CQD ('Come Quick, Danger') distress calls were put out using the relatively new radio system, accompanied by flares sent into the still night sky. A nearby ship saw the flares, but the Californian's radio operator had gone to bed and the CQD was not heard. Instead, the crew thought Titanic was enjoying a late-night fireworks display.

It is well known that Titanic didn't carry enough lifeboats for all those on board, as they used too much room on the first class decks and were thought to impede passengers' ability to promenade. So she set sail with only 20 lifeboats, including four collapsibles, with a total potential capacity of 1,176 people. To any modern sensibilities, missing lifeboats for over 1,000 passengers seems like a dreadful, careless oversight, but nothing more was required by law or the British Board of Trade. While reckless, this was standard practice.

With so few lifeboats, there was never a hope of saving all those on board; lives had to be prioritized. In this pre-war 'angel in the house' age, it was theoretically the women and children who were rescued first. As a result, a number of prominent men went down with the ship, refusing to save themselves while there were still women aboard. Many feminists of the time were against this chivalrous act, arguing that it suggested men were the protectors of women. Guggenheim even got dressed in evening wear for the occasion, telling his steward:

Many feminists of the time were against this chivalrous act, arguing that it suggested men were the protectors of women. Guggenheim even got dressed in evening wear for the occasion, telling his steward:

We've dressed up in our best and are prepared to go down like gentlemen. I think there is grave doubt that the men will get off. I am willing to remain and play the man's game if there are not enough boats for more than the women and children. I won't die here like a beast. Tell my wife, if it should happen that my secretary and I both go down, tell her I played the game out straight and to the end. No woman shall be left aboard this ship because Ben Guggenheim was a coward.Cited in Stephanie Barczewski, Titanic 100th Anniversary Edition: A Night Remembered (London: Continuum Publishing, 2011), p.62.

One of the most abiding stories of that night is the heroism shown, not just by passengers, but also by the crew. The engineers, for example, stayed at their posts, keeping the ship's generators running until almost the very end. Thanks to their sacrifice, the lights remained on, preventing panic while guiding rescue ships towards the stricken craft. Nor did the band abandon ship, instead soothing and calming the passengers by continuing to play on deck. The managers of White Star Line were less altruistic, however, refusing to pay the band's families any compensation, and instead sending them bills for loss of equipment and uniforms.

But filling the lifeboats was not done fairly, and a brief glance at the lists of survivors shows class had as much to do with survival as gender. According to the statistics from the American enquiry, 60 per cent of all first class passengers survived the disaster, but only 24.5 per cent of those from third class did. Nor did gender or age save the poorer passengers: an impressive 93 per cent of all first class women and children survived, compared with only 47 per cent of those from third class.

Cameron's film, and a certain amount of commentary, have suggested the lower classes fought this bias towards the wealthy, but there seems little in the record to confirm this: there were no crew members shooting at passengers, and those travelling steerageThe part of a ship providing the cheapest accommodation for passengers. were not forcibly kept below decks. Instead, it seems the situation was accepted by one and all. What is even more shocking, as Willis puts it, 'is how few of the accounts from first-class passengers mention the terrible loss of life they must have witnessed, and how many are concerned with the loss of jewellery, furs and pets.' Willis, Shipwreck, p.195

Willis, Shipwreck, p.195

To make the matter worse, lifeboats were not launched to full capacity: the first lifeboat launched had a maximum capacity of 40 people, yet launched with only 12. Others that were capable of holding 65 held only 28 survivors each. It is easy to blame the crew, unwilling to cram first and third class travellers in together, kow-towing to ridiculous ideas of decorumProper and tasteful behaviour. But nothing is that simple. The crew had no idea how long the ship would stay afloat, and so rushed to ensure the boats were used at all, rather than sinking with Titanic. Furthermore, many passengers refused to board the lifeboats, unwilling to believe Titanic was going down, and simply didn't get to them in time. Others refused to leave loved ones on board, and chose to stay together: the only child from first class to die had refused to leave her mother who, in turn, had refused to leave her husband.

As well as the statistics, individual human stories have survived the disaster, thanks to the enquiries held afterwards and a number of memoirs published. The last survivor of Titanic, who was just nine weeks old when the ship sank, died as recently as 2009. Millvina Dean had been travelling with her family – father, mother, and brother – from Southampton to Kansas, where they intended to open a tobacconists. Her father died, but her mother took her and her brother back to Southampton, where they remained more or less for the rest of their lives. Violet Jessop was another traveller on Titanic. Working as a stewardess, she had already survived a collision on Titanic's sister ship, HMS Hawke in 1911. She survived Titanic and continued working for the White Star Line. She was aboard Titanic's other sister ship, the hospital ship Britannic, when it hit an underwater mine in 1916 and sank within the hour. She survived this disaster as well, became known as 'Miss Unsinkable', and lived until she was 83.

At 2:20 on the morning of the 15 April 1912, just two hours and forty minutes after the collision with the iceberg, RMS Titanic broke in two and sank. She crashed onto the ocean floor, almost two and a half miles beneath the surface, with such force that the decks tore apart and debrisScattered pieces of rubbish or remains was scattered over a square mile. Over 1,500 people died in the disaster. Just as with the crew and passenger numbers, so there is no agreement on the numbers who died. The lowest estimate is 1,490, and the highest is 1,517. Of those, 549 came from Southampton: 12 were passengers and the rest were crew. Jobs on Titanic were sought after, not just because of the glitz and glamour associated with this new and luxurious ship, but because a coal workers' strike at the beginning of 1912 had led to many ship workers being laid off: unemployment in Southampton was high. Just 706 survivors were rescued by RMS Carpathia, who arrived at the scene after 4am on the 15 April.

Just as with the crew and passenger numbers, so there is no agreement on the numbers who died. The lowest estimate is 1,490, and the highest is 1,517. Of those, 549 came from Southampton: 12 were passengers and the rest were crew. Jobs on Titanic were sought after, not just because of the glitz and glamour associated with this new and luxurious ship, but because a coal workers' strike at the beginning of 1912 had led to many ship workers being laid off: unemployment in Southampton was high. Just 706 survivors were rescued by RMS Carpathia, who arrived at the scene after 4am on the 15 April. This figure is according to the American report; the British report recorded 711. By that time, anyone who had gone into the water - rather than the lifeboats - would have been in the freezing Atlantic ocean for almost two hours, a feat impossible to survive. Only around one-third of Titanic's original passengers finally made it to New York, cold and shocked, but alive.

This figure is according to the American report; the British report recorded 711. By that time, anyone who had gone into the water - rather than the lifeboats - would have been in the freezing Atlantic ocean for almost two hours, a feat impossible to survive. Only around one-third of Titanic's original passengers finally made it to New York, cold and shocked, but alive.

During the days that followed, more boats went to the spot where Titanic sank to recover as many bodies as possible. The corpses of 328 men, women and children were recovered by ships chartered by the White Star Line, and a further five were recovered by passing steam ships. Of them, 119 were buried at sea and the rest were taken to the Canadian city of Halifax. Fifty-nine were reclaimed by their families, and the remaining bodies, many of whom were unidentified, were given formal burials in Canada.

Two enquiries started almost immediately afterwards: the first, in America, began the day following the arrival of the survivors in New York, and called 86 witnesses, including Ismay. The second was held in Britain, commencing 11 days after its American counterpart. The enquiries, while too late for those killed, helped to make shipping safer for future generations. A number of recommendations were made - all based on what we would consider to be common sense - which quickly became standard practice: vessels were required to reduce speed in hazardous conditions and should carry enough lifeboats for all on board. Ships' radios, still in their infancy, had to be manned 24 hours a day.

There were many reasons both for the shipwreck and for the huge loss of life that followed: the decision to go full steam ahead, not enough lifeboats and incorrect use of the ones that were there, mismanagement of both Titanic and the other ships nearby; the societal issues which placed promenading above life, and the financial issues which put company profits above all else. But Sam Willis has pointed out another irrefutable reason: icebergs in that particular stretch of water. If Titanic had sailed the route today, she would not have come near an iceberg during April: water temperature around there has risen by 0.5°C, and icebergs simply do not litter that route any more.

Things to think about

- Why do we find the story of RMS Titanic so fascinating?

- Was the disaster inevitable?

- Who was ultimately to blame for the sinking of Titanic?

- Did any good come out of the disaster?

Things to do

- Look through the two enquiries held into the sinking of Titanic in 1912, which are available in their entirety online. They can be found here.

- Southampton's SeaCity Museum contains much information on Titanic. You can find out more information about visiting here. They also have a Titanic Trail, which can be downloaded here.

Further reading

Although originally published in 1955, Walter Lord's A Night to Remember is still considered the definitive work on the sinking of Titanic. 'Miss Unsinkable', Violet Jessop, released her own memoirs on Titanic,Titanic Survivor: The Memoirs Of Violet Jessop, Stewardess, giving a very personal view of the disaster.

- Log in to post comments