The Death of Emily Davison

Key facts about Emily Davison

- Emily Wilding Davison is famous for stepping in front of George V's horse at the Epsom Derby

- She died in hospital four days later

- She was a suffragetteA woman seeking the right to vote through militant organised protest. The term was first used as mockery, but the Suffragettes embraced it and turned the'g' into a hard one, calling themselves 'suffra-GETs'. A woman seeking the right to vote through militantFavouring the use of violence and confrontation in the support of a cause. organised protest. The term was first used as mockery, but the Suffragettes embraced it and turned the'g' into a hard one, calling themselves 'suffra-GETs'. and supporter of women's rights

People you need to know

- Emily Davison - suffragette and member of the Women’s Social and Political Union.

- George V - King of Great Britain between 1910 and 1936.

- Herbert Jones - the racehorse Anmer's jockey.

- David Lloyd George - Liberal politician who served as chancellor of the exchequer between 1908 and 1915, and as prime minister between 1916 and 1922.

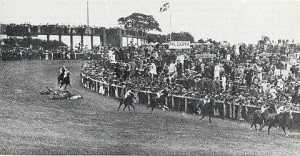

On 4 June 1913 suffragette The term was first used as mockery, but the Suffragettes embraced it and turned the 'g' into a hard one, calling themselves 'suffra-GETs'. Emily Davison stepped in front of King George V’s horse, Anmer, at the Epsom Derby. She was trampled and died in hospital four days later. She is recognised as a hero and martyr for women’s rights, although most of her actions today would be considered terrorism.

The term was first used as mockery, but the Suffragettes embraced it and turned the 'g' into a hard one, calling themselves 'suffra-GETs'. Emily Davison stepped in front of King George V’s horse, Anmer, at the Epsom Derby. She was trampled and died in hospital four days later. She is recognised as a hero and martyr for women’s rights, although most of her actions today would be considered terrorism.

Women's suffrageThe right to vote in elections. The right to vote in elections.

Before the First World War there were many arguments against female suffrage. Doctors advised that women’s brains and bodies were unsuitable for political thinking, which could lead to infertility or increased ‘manliness’. Women had no legal status separate from their husbands, so there was no room in law to give them the vote. Furthermore, as good daughters and wives, they would likely be swayed in their political choice by their fathers or husbands. Other people thought it was just not ‘proper’ for women to vote. Many women, as well as men, saw the sound logic in these arguments, and in 1889 some 2,000 prominent women signed a petition against female enfranchisementTo be given citizenship, particularly the right to vote..

However, as more men were included in the electorateAll the people in an area who are able to vote. All the people in an area who are able to vote. during the 19th century, the calls for female suffrage became louder and more violent. For much of the modern period, most men have also been denied the right to vote. In 1432, Henry VI passed a law that only male owners of property worth at least £2 (which could be worth as much as £800,000 in today's money) could vote. This went largely unchanged until the 1832 Reform Act, which allowed about 14% of the adult male population to vote. It was only in 1918 that all men over 21 were given the vote. By the start of the 20th century, the movement had gained considerable momentum, and by 1914, supporters were bombing schools, public buildings and churches (including Westminster Abbey), with suffragettes chaining themselves to railings outside Downing Street and Buckingham Palace. When arrested and imprisoned, they went on hunger strikeWhere a prisoner refuses to eat food as a form of protest. Where a prisoner refuses to eat food as a form of protest. . The hunger strikers were force-fed, attracting sympathy from the press and public, causing the government to introduce the quite probably illegal Cat and Mouse Act (where hunger strikers were released from prison and then re-arrested after their health had improved in order for them to continue their sentence).

For much of the modern period, most men have also been denied the right to vote. In 1432, Henry VI passed a law that only male owners of property worth at least £2 (which could be worth as much as £800,000 in today's money) could vote. This went largely unchanged until the 1832 Reform Act, which allowed about 14% of the adult male population to vote. It was only in 1918 that all men over 21 were given the vote. By the start of the 20th century, the movement had gained considerable momentum, and by 1914, supporters were bombing schools, public buildings and churches (including Westminster Abbey), with suffragettes chaining themselves to railings outside Downing Street and Buckingham Palace. When arrested and imprisoned, they went on hunger strikeWhere a prisoner refuses to eat food as a form of protest. Where a prisoner refuses to eat food as a form of protest. . The hunger strikers were force-fed, attracting sympathy from the press and public, causing the government to introduce the quite probably illegal Cat and Mouse Act (where hunger strikers were released from prison and then re-arrested after their health had improved in order for them to continue their sentence).

Emily Davison

Emily was an intelligent woman from Kent. In her younger years she was given a bursary to study English literature and foreign languages at Royal Holloway College, although she had to drop out after her father died. She went on to become a governess and in 1906 joined the militant Favouring the use of violence and confrontation in the support of a cause. Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). When her activities as a suffragette made it impossible for her to take work as a governess, she remained unemployed, writing occasional articles as a journalist and living on gifts from her family. She was never employed by the WSPU, although 110 people were by 1911.

She was never employed by the WSPU, although 110 people were by 1911.

By 1913 Emily had already served several prison terms for throwing rocks at ministers’ cars, setting fire to pillar boxes, going on hunger strike, and attacking a man she wrongly thought was David Lloyd George. She had also flung herself off a prison balcony and down a 30ft stairwell. On the night of the 1911 censusAn official count or survey of the population. In Britain, a full census is run every ten years. An official count or survey of the population. In Britain, a full census is run every ten years. , she sneaked into the Houses of Parliament and hid in a broom closet, so she could officially give her address in the census as the Houses of Parliament. There is now a plaque inside the cupboard.

The Epsom Derby

Although no-one really knows what she was thinking on 4 June, it is likely that she hoped her actions at the racecourse would enhance and advertise the suffragette movement. We don't know whether she intended to commit suicide, as she had a return train ticket, and it has even been suggested she was just trying to cross the racecourse and mistimed it. However, she had made her will in 1911, which perhaps suggests death was on her mind. Furthermore, she said to a prison doctor in 1912 that 'a tragedy is wanted' to raise awareness of the cause. Did she think that she could be this tragedy?

Whatever her reasons, she was labelled as a mentally ill fanatic, and the event shocked several previous supporters into withdrawing their support, many of whom saw her actions as an insult to the King. This loss of support can't, however, be entirely blamed on Davison. The increasingly violent acts undertaken by the WSPU had been reducing public favour for a while. Neither did the movement get the press coverage Davison had been hoping for, making 'less impression than the fact that the favourite and first past the post of the best-attended Derby in years was disqualified in favour of a 100-1 outsider.'

This loss of support can't, however, be entirely blamed on Davison. The increasingly violent acts undertaken by the WSPU had been reducing public favour for a while. Neither did the movement get the press coverage Davison had been hoping for, making 'less impression than the fact that the favourite and first past the post of the best-attended Derby in years was disqualified in favour of a 100-1 outsider.' David Horspool, The English Rebel: One Thousand Years of TRouble-making from the Normans to the Nineties, London: Penguin (2009) p.361 When the press did mention it, instead of focusing on her death, they concentrated on the welfare of the jockey and horse (which had to be put down). The jockey, Herbert Jones, committed suicide in 1951, having been ‘haunted by that woman’s face’.

David Horspool, The English Rebel: One Thousand Years of TRouble-making from the Normans to the Nineties, London: Penguin (2009) p.361 When the press did mention it, instead of focusing on her death, they concentrated on the welfare of the jockey and horse (which had to be put down). The jockey, Herbert Jones, committed suicide in 1951, having been ‘haunted by that woman’s face’.

Emily's funeral took place on 14 June 1913 and was accompanied by a spectacular procession of other suffragettes, carrying a large cross at the front. This subdued some of the usual 'rowdies' who were often hired to heckle suffragette events, and many were reported removing their hats in respect.

There is not a chance, in today’s world, that she could ever have made the impact she did at the time. The UK currently defines terrorism as any action or threat of action ‘designed to influence the government’ and ‘made for the purpose of advancing a political, religious or ideological cause’. Not just Emily Davison, but the whole suffragette movement, would have been permanently jailed before it started.

Things to think about

- Did Emily Davison intend to commit suicide?

- Did Emily's actions make an impact, and was this impact the one she would have hoped for?

- Were the actions of Emily and other suffragettes acts of terrorism?

Things to do

- Look through newspaper reports of the race and Emily's death and funeral. How do you think the British press saw her actions, and the actions of the suffragettes in general?

- The Parliament website has many primary sources relating to Emily and the suffragettes online. Click here to look through them.

Further reading

Sadly, there are no good recent biographies of Emily Davison. However, there are several books on the suffragette movement as a whole. A very good, concise guide is Paula Bartley's Votes for Women (3rd ed. 2007), which is part of the Access to History series. Essential reading for the student of the Women’s Social and Political Union is The Suffragette by Sylvia Pankhurst.

- Log in to post comments