The threat to Stonehenge

Guest article by Dave Cross.

2018 marks a centenary of Stonehenge being gifted to the nation, yet access to it is more restricted than ever. The ability to see the landmark from a passing car window is under threat as plans resume to place a tunnel underneath it, while historical byways are ‘experimentally’ closed off. But this threat is far less significant than that of the consequential destruction of a hugely important archaeological and sacred landscape.

Stonehenge has loomed large on the landscape and the nation’s psyche for over 4,000 years. At the turn of the nineteenth century, it was part of the Amesbury Abbey estate in Wiltshire, owned by the Antrobus family. In 1901, a lawsuit to prevent Sir Edmund Antrobus from charging a shillingOld British currency, before it went decimal. There were 20 shillings in a pound (£), and 12 pennies (d) in a shilling.Old British currency, before it went decimal. There were 20 shillings in a pound (£), and 12 pennies (d) in a shilling.Old British currency, before it went decimal. There were 20 shillings in a pound (£), and 12 pennies (d) in a shilling.Old British currency, before it went decimal. There were 20 shillings in a pound (£), and 12 pennies (d) in a shilling.Old British currency, before it went decimal. There were 20 shillings in a pound (£), and 12 pennies (d) in a shilling.Old British currency, before it went decimal. There were 20 shillings in a pound (£), and 12 pennies (d) in a shilling.Old British currency, before it went decimal. There were 20 shillings in a pound (£), and 12 pennies (d) in a shilling.Old British currency, before it went decimal. There were 20 shillings in a pound (£), and 12 pennies (d) in a shilling. entrance fee was lost and access remained restricted to those who could pay. Over the next fourteen years the site fell into a state of disrepair – thanks in part to the carriage loads of tourists bent on knocking souvenir lumps out of the stones and scratching in their names for prosperity.

Come 1915, the site and its surrounding thirty acres went up for auction. Purchased for a mere £6,600, it was described as ‘poor bidding’ at the time: the site held a value of just under half a million in modern money. The new owner, Cecil Chubb, exchanged Stonehenge for a knighthood in October 1918, by gifting it to the nation. A key term in the agreement was that the entrance fee should be fixed at one shilling forever more. Today visitors have to pre-book and a timed family ticket costs £45.50 – conditions of entry being far stricter than the Edwardians endured.

In the 1920s, the government purchased an additional 1,440 acres around the site and placed it under the charge of the National Trust to ensure that the ‘valuable archaeological remains of the site be protected from the plough.’ The Trust has gone on to almost double this land holding.

Until recently, the biggest controversy the site attracted was caused by the annual Free Festival, ending in 1985 with ‘The Battle of Beanfield’, as 1,200 police officers attacked and savagely beat the peace convoy of 600 New Age Travellers. A year later, the site was designated as a UNESCOUnited Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. World Heritage Site.

By 2002, moves were afoot to locate a tunnel next to the site, sending the A303 traffic underneath rather than past it, ‘to safeguard the World Heritage site for future generations.’ Critics at the time pointed out that this was a simply a method of ensuring people didn’t stop to look at the stones for free. The ensuing public outcry and issuing of public letters partially achieved its aim. In 2014, the site was rolling out a new approach. Talks about a tunnel under the site were put back on the shelf (but not dropped), mock NeolithicThe 'New Stone Age'. See 'The Chronology of the Stone Age'.The 'New Stone AgeThe earliest part of human prehistory, running from about 3.3 million years ago until (in Britain) about 2500BCE. It is defined by the use of stones (rather than metals) as tools.'. See 'The ChronologyThe arranging of events in the order they occurred in time. of the Stone Age'.The 'New Stone AgeThe earliest part of human prehistoryThe time in the past that happened before history began to be recorded., running from about 3.3 million years ago until (in Britain) about 2500BCE. It is defined by the use of stones (rather than metals) as tools.'. See 'The ChronologyThe arranging of events in the order they occurred in time. of the Stone Age'.The 'New Stone AgeThe earliest part of human prehistoryThe time in the past that happened before history began to be recorded., running from about 3.3 million years ago until (in Britain) about 2500BCE. It is defined by the use of stones (rather than metals) as tools.'. See 'The ChronologyThe arranging of events in the order they occurred in time. of the Stone Age'.The 'New Stone AgeThe earliest part of human prehistoryThe time in the past that happened before history began to be recorded., running from about 3.3 million years ago until (in Britain) about 2500BCE. It is defined by the use of stones (rather than metals) as tools.'. See 'The ChronologyThe arranging of events in the order they occurred in time. of the Stone Age'.The 'New Stone AgeThe earliest part of human prehistoryThe time in the past that happened before history began to be recorded., running from about 3.3 million years ago until (in Britain) about 2500BCE. It is defined by the use of stones (rather than metals) as tools.'. See 'The ChronologyThe arranging of events in the order they occurred in time. of the Stone Age'.The 'New Stone AgeThe earliest part of human prehistoryThe time in the past that happened before history began to be recorded., running from about 3.3 million years ago until (in Britain) about 2500BCE. It is defined by the use of stones (rather than metals) as tools.'. See 'The ChronologyThe arranging of events in the order they occurred in time. of the Stone Age'.The 'New Stone AgeThe earliest part of human prehistoryThe time in the past that happened before history began to be recorded., running from about 3.3 million years ago until (in Britain) about 2500BCE. It is defined by the use of stones (rather than metals) as tools.'. See 'The ChronologyThe arranging of events in the order they occurred in time. of the Stone Age'. houses were erected and canapés were enjoyed by the great and the good at the opening of the new visitor centre. One of those attending the opening, author Will Self, wrote: ‘The new Stonehenge visitor centre was packed; it was showery outside but inside the atmosphere was thick with the distinctive aroma of wet Gore-Tex – a smell I always associate with the British heritage industry … The archaeological folk smelt different from the trippers … more heathery.’

Self added that he was, ‘struck by how there are two main historical timelines at Stonehenge, the history of the monument itself and the history of these explanations of it; and that it's in the interaction between the two that our culture has given birth to its own peculiar theology of deep time, for each era cannot help but seek out a past that it finds inspiring – or at least congenial.’

‘Congenial’ is not how the queues of cars and lorries passing slowly by could be described. Current visitors to the area, making their way between London and Devon, can easily see there is a traffic problem. The single-lane road clogs up with transport and delays are frequent.

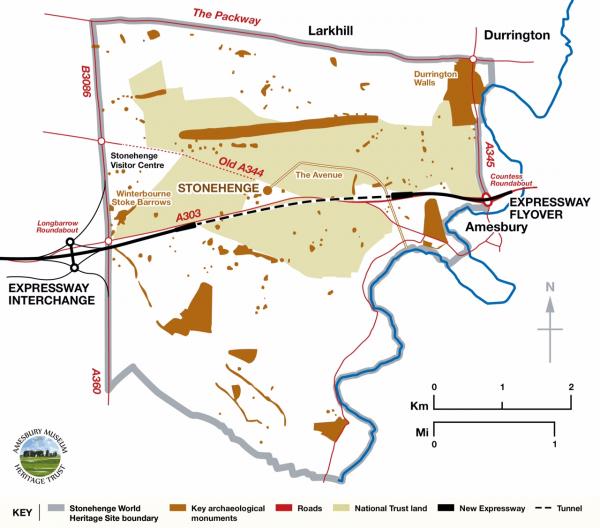

But the proposed solutions, while helping to rectify the temporary – in the grand scheme of things – traffic problems, will have a negative impact on this incredibly important ancient site. They include turning the A303 into a dual carriageway and constructing a deep bored tunnel not far south of the henge. This is the government’s preferred option, following consultation in 2017 on the plans (see map). The eastern entrance to the tunnel would be cut just north of the present A303 and marry with the current dual carriageway. The one to the west was initially planned to exit in alignment with the midwinter sunset and is now proposed further north. Despite changes to the plans moving the tunnel to just south of the current A303, the problems are still staggering. As Tom Holland explains, ‘Huge four-lane highways, intersections, tunnel portals will be built. We’re not talking here in terms of a hundred years; we’re talking here in terms of millenniaThousands of years.Thousands of years.Thousands of years.. It would be a tragedy and a disgrace if the legacy of our generation to posterity is this obscenity of a tunnel.’

In an earlier video, Holland points to the eastern portal proposal and its significance: ‘Finds being made here go back 10,000 years. If you build a tunnel here then all prospect of finds in the future would be obliterated. Stonehenge did not exist in isolation; stretching all around it are traces stamped, not just in the fields, but also in the very subsoil of Salisbury Plain. It’s the most archaeologically significant landscape anywhere in Europe. Lose it to the tunnel and you lose our beginnings.’ 'It would be an act of vandalism and shame our country and our generation.'

‘Future generations are going to look at us,’ adds archaeologist Julian Richards, ‘and go: what were you thinking at that time? What have you done to this absolutely incredible landscape?’

Will Self’s article ends by pondering the nature of our relationship with Stonehenge: ‘There can be no doubt: we are engaged in a degraded form of meta‑ancestor worship.’ Just how might those ancestors view the tunnel? And will future generations laud us for the engineering skill that covered up our ancestral beginnings; or will they feel we have irredeemably ruined their heritage and failed in our duty to safeguard the site? A century ago, the government ensured that valuable archaeological remains were protected from the plough, but the government now seems to think they’re fair game for the tunnel borers.

For more information about the proposed changes to the Stonehenge landscape, visit the Stonehenge Alliance.

If you would like to know more about Stonehenge or even general prehistoryThe time in the past that happened before history began to be recorded., check out our recommended reading page: https://www.gethistory.co.uk/history-books/prehistory

- Log in to post comments