Elizabeth Baigent: In Conversation

As the final part in a trilogy of articles on space and history, I met up with Oxford professor Dr Elizabeth Baigent, University Reader in the History of Geography and SCIO Senior Tutor at Wycliffe Hall, after a lecture she gave as part of the Bodleian Libraries' Talking Maps exhibition. It was a great pleasure to hear her speak in more detail about the history of mapping.

In your lecture you identified three key areas of map purpose: jurisdiction, property and use. Could you give some examples of what you meant by this?

I think most people are used to thinking of maps pretty much exclusively as things that you use for getting from A to B. That's one of the primary reasons that people use maps, but it's not the only reason that people use them. I specialise particularly in maps of property and maps of jurisdiction. To take the second one first, I think most people are familiar with maps that divide the world into countries (though you can divide the world in other ways, for example, you can divide the world into vegetation types or climatic zones that don't obey political boundaries). But making maps to show political jurisdictions is really quite a new way of thinking about the relationship between land and jurisdiction. I suggested in my lecture that, in the early modern period, rulers started to realise the potential connection between land and jurisdiction and how maps could help them to rule their lands, to know the countries that they were dealing with. Joseph II, the Habsburg emperor, said that to rule well one must first know the country that one is ruling. One of the ways he did this was that he tried to map his far-flung lands that he knew he couldn't investigate personally and on the basis of these maps he could rule 'better', by which he meant to be a typical Enlightenment monarchA king, queen, or emperor. And this is typical of people who start to realise that a map can help them to know places from which they're distant. They can help you to see towns, rivers, natural resources - all kinds of information can be displayed on a map. Monarchs began to realise that maps were a good way for them to rule well.

Some of the earliest English maps for example were drawn by royal authorities who were rather nervous about what was going on in farther-flung bits of the country and really wanted some idea of how they could secure central royal rule over all of the country. An English example of this sort of map – which by the way are very nice to look at - are those by Christopher Saxton from the sixteenth century. He was commissioned by one of the court officials of Elizabeth I to map the country, county by county. He went to all the counties, mapping various features of the kingdom, and the results were bound together in a lovely atlas, our first county atlas. And not only on the front page but on every map, the Royal Arms are there, all the way through, an emblemA heraldic device or symbol that forms the badge of a nation, organisation, or family. that royal jurisdiction extended to all bits of the country. So there was a practical reason for wanting maps for better administration, but also an iconographic reason, that you really can't miss that these are lands over which the queen rules.

Another type of map is of property ownership and use of land. Sometimes these are very large-scale maps, meaning that things appear large on them and you can identify property boundaries. That may seem a rather anodyne thing to do to most people now, but actually it's really rather significant. In many countries the process of mapping individual property boundaries was carried out by central state authority as a means of enforcing the central state jurisdiction everywhere in the country and a means of establishing that the power in charge, when it came to property transactions and property taxes, was the central state. There was a very famous example instituted by Napoleon not only in France but in all the countries which were part of his empire, in order to establish imperial ability to extract tax effectively. But also it was a way the imperial authority stamped its mark, if you like, on everyday life and on the smallest kind of property boundaries.

In England we have a lot of property maps made by estate owners wanting to administer their properties more effectively, and also to stick them up in their hallways so that as soon as you walked into their houses, their membership of the landowning class and their local importance wasn't lost on you. You can see those kinds of things in National Trust houses. We do have lots of property maps which were involved in the enclosure movement in the nineteenth century, when land shifted from being communal fields with some kind of communal decision-making attached to them and often common grazing land, to being chopped up into individual plots which were exclusively owned by each property owner: a pre-capitalistSupporting an economic and political system in which a country's trade and industry are controlled by private owners for profit, rather than by the state. farming system to a capitalist one.

Across history are there identifiable trends and changes in the way that maps have been produced and used?

Yes, and we also have to consider that there are some periods and societies where we don't have maps at all. It's not a given that people draw and use maps. But in fact maps have been found in lots of societies, both Western ones that we are familiar with but also other societies. So North American native populations, for example, had maps. They've arisen in a lot of different places spontaneously but in the West, in the middle ages, maps were rare. We may have lost many medieval maps of course, but certainly there are increasing numbers of maps made from the early modern period onwards.

Changes in the technical side of how maps have been produced and used is something that I'm not an expert in, but generally people have moved from making maps by looking at the ground in various ways, perhaps measuring it with chains or rods, and essentially drawing a picture of it, to much more modern methods where you go out and collect numerical data which are the primary sourceis information that comes from or close to the event or person being studied. from which you then make the map. So we see a trend towards what we would think of as being a more scientific method that means there's more standardisation and you don't get local artistic habits and practices coming through.

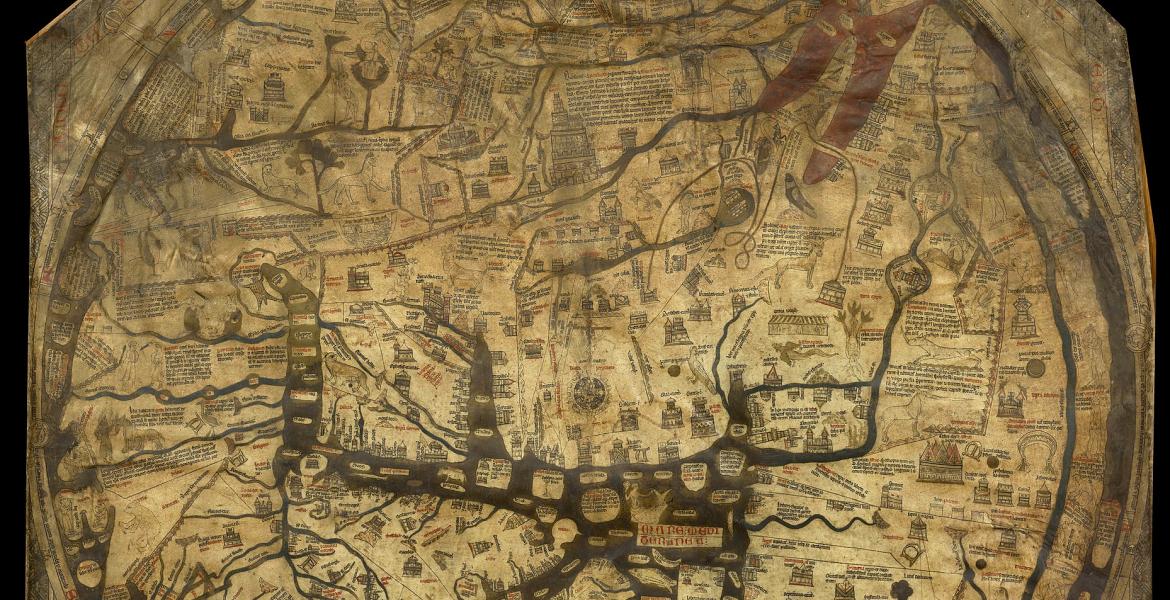

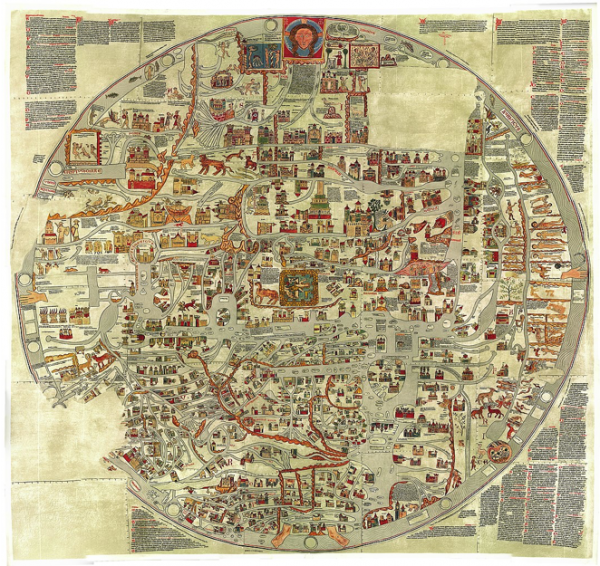

In the lecture you talked about sacred maps and you gave the Ebstorf mappa mundi as an example of that. Are there interesting maps available from other religious traditions?

Yes, there are. The only ones I am familiar with, however, are Christian maps. Readers may be familiar with the Hereford mappa mundi which is the most famous English example and there's a lovely website about that so people can see it in a lot of detail. Like all mappae mundi in the Christian tradition and like religious maps in other traditions, it's trying to tell us something about the cosmos, a theological representation of the world and our place within it. It's nice that the Bodleian Library in Oxford marked its 400th anniversary by buying The Book of Curiosities which is a very interesting collection of Islamic maps.

In the Q&A after the lecture one of the audience members spoke about maps compiled from aerial photographs of parts of Asia, describing it as being apolitical. Do you think it is possible for a map to truly be apolitical?

During the Second World WarA global war that lasted from 1939 until 1945. aerial reconnaissance missions were regularly flown and the idea of aerial photography as a way of getting a quick and accurate understanding of the landscape became very widespread. People began to realise that with expert analysis you could get a very sophisticated and detailed idea of the landscape. In fact, you can see some things from the air which you can't see from the ground: people may be familiar, for example, with instances where archaeological features have been discovered from aerial photos, and in wartime it was possible to reveal even those things which the enemy wanted to keep hidden. After the war people realised that aerial photography could be a very cheap and effective way of mapping areas of the world that lacked maps. The Directorate of Colonial (later CommonwealthThe countries once part of the British Empire; the interregnum in Britain; or the welfare of the public.) Surveys made maps from aerial photographs of African countries when good ones were not available. We've talked about the idea that people might try to see what was there in wartime, maybe hidden by camouflage, and analysis had to be sophisticated to interpret that. And then you have to make decisions, as you always do with maps, about what you're going to put on the map and what you're going to leave off the map.

Any selection is therefore a political process. Very many countries choose to leave out sensitive military installations, for example, in their maps. We are very good in the West at pointing out what the Soviets did with their maps, moving towns around to try to confuse the enemy, but Western mapping authorities also removed sensitive military installations. In most Western countries (and probably elsewhere) national topographical mapping originated for military purposes. For example, our Ordnance Survey, as one can tell from the title, has its origins in the military and strategic needs of the country. Many maps are political. Some content may be determined by commercial reasons, but very many maps have a political side to them as well.

The topic of maps creating a kind of national identity is very interesting but how do you feel maps have also been used to construct a sense of regional identity, and I'm speaking here of on a small scale within a country?

We were talking about Saxton maps from the sixteenth century, and they began a trend for the popularity of the county map and that went on until the early nineteenth century. And people, particularly those who subscribed to such maps or were wealthy enough to buy a large county map to go in their library, were saying that they were proud of their locality. They were landowners, very often also county officials, they would go to county balls and go to the county town for the social season. The county is an important institution and people would be proud not only of their county as it existed, but also of all the important historical places within their county. There was pride in the county as a unit of administration and a social unit but there's also pride in its long history.

Finally, for somebody who's interested in getting started in thinking about issues related to maps and thinking in this way, are there any particular texts and books that you would recommend as a good beginning or foundation?

If you want a really detailed account of any particular map, I can warmly recommend what's intended to be the definitive account of mapping, called The History of Cartography, a huge multi-volume project published by the University of Chicago Press. The first volumes are freely accessible online, so I can warmly recommend that people go there if they want to read a really detailed look at any map.

A book published by the British Library, English Maps: A History, is nice because it takes you through all different kinds of maps and it's written for a general audience by real specialists in the field. There are also lots of series of lectures which I warmly recommend. In Oxford there is one which I help to convene called TOSCA, The Oxford Seminars in Cartography, which happens at the Bodleian Library. In London there is a series called Maps and Society at the Warburg Institute. Cambridge has a series at Emmanuel College, and there are others at the national libraries of Scotland and Wales. I can recommend that people come along to those where they’ll be very welcome even if they don’t know much about maps.

Further reading

In addition to the suggestions Dr Baigent gave, a book well worth reading is Mark Monmonier's How to Lie With Maps, which covers the more political aspects of mapping.

- Log in to post comments