Alice Loxton: In Conversation

Alice Loxton has been called 'the next big thing in history'. At just 27 years old, she has authored an acclaimed book, worked with some of the biggest names in history, and is without doubt one of the industry's biggest influencers, with over a million followers on Instagram and 600,000 followers on TikTok. We met up with her at Chalke Valley History Festival to talk about satire, the nature of fame, and her passion for bringing history to new audiences..

Tell me about your book, Uproar!

Uproar! came out in March 2023. It's about a set of revolutionary artists called James Gillray, Isaac Cruikshank and Thomas Rowlandson, who lived and worked in the late-eighteenth century and at the start of the nineteenth century – the Napoleonic era. I first came across them in my late university years, and I was so impressed by how weird, how wacky, how ahead of their time, how startlingly modern they were; and how so often they correlated with the way news is reported today and with our own immediate world of social media.

I was very surprised to see that they'd never really been covered in a public, popular-history way – although there have been academic books about them, and more general books about them and their era, such as City of Laughter by Vic Gattrell – so I decided to write quite a specific group biography. The art that they were making was satiricalCriticising something, particularly social or political, in a humorous way., political prints that were on display in the print-shop windows in London. So they shaped a lot of London, a lot of society. Perhaps most importantly, they created the myth that Napoleon was a short man. Napoleon was not a short man; he was of average height. But it was these prints, which were part of war propagandaBiased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view. at the time, that have led us to think that.

Why do you think there hasn't been a popular history book about them before?

Basically, during the nineteenth century they went wildly out of fashion. The Victorians thought they were very vulgar and crude and not something that should be in high society, or in any sort of society. Queen Victoria was destroying some of them in the royal collection. By the mid-century, the plates were being destroyed, which was the original artwork. Since then, I don't think they've really recovered and they've become this quite nerdy, niche interest for people who are print collectors or students of that era. They're not a part of a general history at all, and I feel like they don't really have a place in people's perceptions of history, which is really odd considering how important they were and also how much fun they are. It is really strange; I don’t know why publishers haven't looked at them before. They've got such a big role to play – they’ve shaped so much of British history and British society, and yet no one's ever written it for a totally beginner audience. So I'm starting a Gillray renaissanceA European revival of learning, art and literature influenced by classical history and culture. It started in Florence, Italy in the 14th century and spread to the rest of Europe in the 14th to 16th centuries..

If you think about the times around them – Hogarth in the eighteenth, Punch in the nineteenth, and David Low in the twentieth centuries – there are some very well-known cartoonists and social commentators. Where do you see Gillray et al fitting in?

Hogarth is often considered as the grandfather of political cartoons and political satire, with his modern moral messages. James Gillray is the 1790s and 1800s. He is considered the father, because he's the next generation. So Gillray and Rowlandson and Cruikshank do follow on from Hogarth's career. There are so many images and jokes within a Gillray print – even the way that people are lying or standing – which are obviously taken from Hogarth. But Hogarth was a painter – people also call him the father of English painting – so I think it's also about how people view prints and paintings in the art world. Even today, people don't think printmakers are established artists. So, because Hogarth was an artist who made paintings, people consider him as definitely part of the story of the history of art. And although the satirists that I was writing about are doing very similar things to Hogarth, because they're doing prints they're not really considered in the same vein.

And then we have the big development in the Victorian period of the newspaper cartoon, and that was things like Punch. But that really came about through a printing development at the beginning of the nineteenth century where you could print much cheaper, you could print double-sided, you could print with images. I think the common thread is the satirical, biting, analytical take on the world and expressing that through one very strong image, which you see running through cartoons to this day.

They were obviously larger-than-life, interesting characters. They must have rubbed shoulders with some fascinating people?

Gillray and Rowlandson and Cruikshank weren't the crème de la crème of society at all, but they lived in London and they could see lots of famous people and they often satirized them. So people like Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, or William Pitt, or Charles James Fox, were the kind of people they were working on. Of course, this was a social circle that was constantly in the satirist's eye. The artists themselves were lower down in society than that, but they'd have overlapped all the time: the satirists would go out and they would draw these people from real life – they would see them walking around London and on the podium at the elections at Covent Garden; they would see them in parliament; they would see them at their clubs. Today you don't really see celebrities so much in that way because it's much bigger and everyone's working in different worlds. But in London in that period, if you wanted to go and see famous people, you could just go and stand on a street and see them, or stand outside their house and see them going in and out.

Do you think the way we understand fame has changed, or has there always been some sort of celebrity culture?

It's really interesting because there are definitely celebrities, and celebrity culture, and celebrity hype in these prints. For example, the Duchess of Devonshire is caricatured and satirized again and again and again: there is a clear obsession with her fashion, with the absolute tiny details, and there’s gossip about her and the scandals of her life. It is like the obsessive fascination we still have today. The prints were very good at encouraging that celebrity culture. What's so interesting about these prints is that they could be produced within 24 hours, so really immediately. If there was a rumour that went around London, and because the satirist was physically in London, they could make a print and get it on the window within 24 hours. That is one of the closest things to the social media reaction that you have today. I think genuinely if you wanted to try to make a comparison between how celebrity exists today and how it exists in the Georgian period, then you should look at Gillray’s prints.

Do you do you have a favourite print?

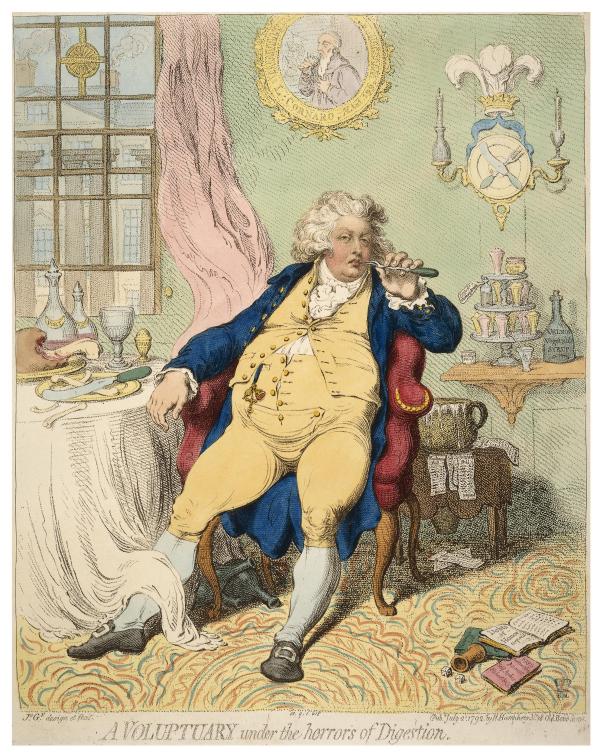

I just love all these prints, because they show an honest view of society – a genuine view of what it was like to live in the Georgian age. There's no Photoshopping, there are no filters here. If you think of George IV, the visual image that comes to mind is probably a painting. And it's probably him dressed in army gear, looking quite noble in a grand setting in a palace. But that's a complete fiction because it's been touched up. It's been edited: his skin is smoothed over; his waistline has been brought in. But what you're seeing in Gillray's images is a completely honest view of things. There's one called A Voluptuary under the Horrors of Digestion. It shows the future George IV when he was still a prince, reclining in a way exactly like a Hogarth print – you can see those links there in this Hogarthian manner. He's in his rooms and he's just finished an enormous feast – there are bones on the floor; there are empty bottles rolling around. His enormous stomach is bulging out, and he's picking his teeth with a fork. That was something that really horrified William Thackeray because he looked back at that and thought, 'Who could have believed the first gentleman in the land would behave in such a way?' There are gambling debts on the floor and there's an overflowing chamber pot. There are medical bottles, from some poor doctor trying to diagnose and treat him for indulging so much. And then in the background, you can see out of the window the building works at Carlton House, which is this huge building project that he had. It was a sinkhole of public money, an appalling waste of money. Also in the background, there's a candle, but the Prince of Wales’s symbol – which usually is three ostrich feathers – has been replaced with a knife and fork. The print is about indulgence: there are all these wonderful little clues, and I think actually, when you piece all of that together, it gives a much more honest and accurate portrait of this person.

What did the targets of the pictures think?

We know that lots of the people who were featured also did collect the prints, as some politicians who are featured in cartoons do today. I've talked to lots of people in politics and sometimes you go to their houses and the cartoons are all across the wall or in the downstairs loo. It's a marker of being someone who's worth talking about. And I think also maybe there was a sense with the royals that actually if they can just take the hit of being satirized, then it's a way for people to feel like their grievances are being aired but actually that doesn't really make a difference.

But there's the story of Charles James Fox, who was one of the real targets: he once went into Hannah Humphrey's print shop, and apparently he said 'Oh dear, there are loads of prints of me all the time.' Then he said, 'Oh, well', and bought one and went on his way. There are other accounts: George Canning, who became prime minister, as an up-and-coming politician made a huge effort to be featured in a Gillray print – he engineered himself socially to try to meet Gillray – because he obviously felt that it was a sign of being somebody worth talking about. There are all these wonderful anecdotes about him, saying how he fell about crying when he went to see the new Gillray print and he wasn't in it. When he eventually was in one, he must have been overjoyed. But, hilariously, the very first appearance that he made was in a nightmarish scene, imagining if the French revolutionary fervour had reached London, with all these horrible things happening to MPs and politicians. So Canning's first appearance is him hanging from a lamppost outside St James's Club. But he probably would have looked at it and thought, 'Yes! Finally Gillray's given me a slot!'

How much did these prints actually help to stir up riot and rebellion?

After the French Revolution, there was a period known as Pitt's 'reign of terror', as people like to call it. Basically there's a massive and quite shocking authoritarian clampdown on what you could say: you couldn't even say things that would criticize the king. It's actually shocking to read, but I think it's really a reflection of how worried they were: they thought that there was a very real chance that revolution could happen here. And knowing what had happened, and hearing the rumours about people reverting to cannibalismThe practice of eating the flesh of the same species (so, human eating human, or dog eating dog)., people had good reason to be very scared. So during that period, there were a lot of rules. Gillray wasn't arrested; his prints weren't inciting revolutionary activity. But some of the printmakers who did cross the line did go to Newgate Prison. The problem then is that they all were there together, discussing all these ideas, and still the print shops were running, so they could talk to their assistants and they'd still be organizing stuff. But Gillray often gets cited as someone who's very patriotic. Of course, he's being tempered by the fact that he doesn't really have a choice to say anything else because he'll probably go to prison. I mean, do you fancy a Christmas at Newgate or at home?! Newgate Prison doesn't sound like a nice place.

You do a lot of work promoting history to younger people. Can you tell me a bit about that?

I do loads of social media content and I just love making little videos about all kinds of history. My real interest is historic buildings and exploring the secrets, whatever you can find there – whether it's priest holes or certain types of building materials. And it's amazing actually, how much you can find from just looking. I feel very confident now that if I went to any street in the UK, I could find something interesting thing about it, even if it's just that the road is there because it was built by the Romans.

Because of that, I have worked with loads of organizations which were really fun. People are keen to get young people involved, and social media is a really good way to do that. What's really nice is museums are keen to be involved. I always film in cathedrals or historic houses or museums, and not once has anyone said, 'You can't come and film.' They're always really keen to up their profile, and it’s been nice to be able to help with that.

Lots of young people are on TikTok and Instagram because it's this amazing tool where you can grow a huge audience. People like publishers are actually approaching these people and giving them a platform and giving them access to book publishing. That is an amazing thing because in the past you'd have to be an academic or you had to have done a PhD at Oxford, which is obviously brilliant but not everybody can do that. So it does bring in a lot of new voices and there is strength to that: it's a lot more diverse, it's a lot younger, it's a lot more fun. But also, obviously, there are limitations which I think we need to look out for: people who are not academics are writing about history and there's every reason that they could not know that much about it.

I think, in the history world, it's like a big, interconnected network where all these different people – social media people, academics, museums, the people who run Chalke Valley History Festival, teachers, the Minister for Culture – all have strengths and weaknesses, and each affects the other. If a historical movie comes out, more people will study that period at university, and no matter how much people put Bridgerton down, it does cultivate that interest in history, even if it's just an aesthetic thing at the start. Bridgerton is basically set in beautiful locations like Bath and Hampton Court Palace, so ultimately, those people who see it are more likely to become members of the National Trust.

What are your next projects?

I do loads of social media stuff. There are lots of festivals, and loads of really hilarious random events that come up all the time, and it's really fun to talk to all sorts of people at them. I'm writing another book, which is coming out in September 2024, all about young people in history: looking at different people's experiences of being a teenager in the past and how it's changed over the years. When we think about teenagers today, we think, 'This is what they're capable of or not'. When they set the curriculum, people worry that teenagers will get stressed because it's too much work or it's not enough work, or they need to be challenged in this way or they're not capable of that. But actually, when you look at history, you suddenly realize that people have gone on Crusade or they've captained a ship: they've done some absolutely incredible things by the time they're 18. Or they have done nothing, but then they go on to become really successful. So I think it's really interesting to know that people are actually capable of a lot, and hopefully it'll be inspiring.

What is the time period you're looking at?

It's starting off with Bede, and it's ending with Vivienne Westwood. I thought it would be interesting to compare; I don't know if any books have ever compared Bede and Vivienne Westwood. It's really hard to get a good mix of people and experiences. It's just British – I was going to do worldwide, but I felt like it loses its focus a bit.

The research must be horrendous.

It's a lot! It's a very broad period. But I'm obviously coming to this not as an expert on Bede, for example. I can't be an expert in all these things – nobody ever really could be. But I will be working with academics who will be checking it and advising me. It goes back to what I was saying about this network of people: I can write it and do the marketing and make this a fun product. But actually it only exists because there are all these amazing academics who do their work behind the scenes and together we can do something quite good.

Imagine you've got the TARDIS. Where would you go in history?

I suppose the question is, do you go somewhere where you can find out a big secret? For example, would you be in the room when the Princes in the Tower die? It would be a great TikTok! So maybe that's what I'd do: I would go and find this out for everybody so we can stop talking about Richard III.

If language were no barrier, which people from history would you have as dinner guests?

Well, because of the book I've been writing, I'm thinking about it almost as if it were an eighteenth birthday party. So, you could get maybe 30 people, each from a different century, and just see what happens. Also, the person I've written a book about is James Gillray, so I'd have to meet him – he would be the number one guest.

- Log in to post comments