Key Facts about the Black Death

- The Black Death spread from the east to Europe in 1347.

- During the next decade it destroyed an estimated 50% of the population.

- It was mainly spread by rat fleas along trade routes.

- Once a person became symptomatic, they usually died within four days.

- It caused massive short-term disruption in religion, the economy, and society.

- The Black Death also contributed to significant changes over the next 200 years, including the decline of serfdom system, whereby peasants owed their lord labour, theoretically in return for protection., and the Reformation.

- The Black Death became endemic in European populations and regularly reappeared over the next 300 to 400 years.

The Black Death looms large in the modern imagination, as it did in the minds of late medieval people. It is a spectre, or shadow, reminding everyone of their mortality, and the briefness of life. The reactions it provoked showed the best, and worst, of the human condition, and its long-term effects contributed to sweeping changes in society. Europe, and the world, would probably be a very different place if not for the Black Death. It is hardly surprising, then, that this cataclysmic event has prompted considerable debate among contemporaries and historians: what caused it, how many people did it kill, how and why did the victims and survivors react in the ways that they did, and exactly what proportion of the responsibility should the Black Death take in the changes that ushered in the early modern era?

Spreading like the plague

It is likely that the Black Death first emerged in central Asia, with the 1330s showing an abnormally high number of deaths. Prompted by a series of climatic changes, it spread eastwards towards China and west through the armies of the Golden Horde and into Persia. By 1346 it was ravaging the armies besieging the Italian stronghold in Kaffa (modern-day Feodosia on the Black Sea coast of Crimea), who spread it to the besieged merchants by lobbing the bodies of their dead over the walls of the city: a medieval form of germ warfare. Those inside the city who were able fled on ships for destinations around the Mediterranean, carrying the plague with them: it was in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), Sicily, and Marseilles by 1347, and was attacking the papal court at Avignon by the spring of the following year. From thence, it spread along inland and sea trading routes, reaching Paris later in 1348 and making landfall at Melcombe Regis, just outside Weymouth in England, in June of that year. During the rest of 1348, and into 1349, it continued to spread north and east across the European landmass, into the lands of the Holy Roman Empire, and parts of northern Italy and the Czech Republic. It developed during the Early Middle Ages and existed through the Early Modern period. and beyond, before reaching Russia in 1351. A few lands were, in the main, spared: Finland and Iceland suffered little thanks to their small populations and minimal trade links, as did an area centred on modern-day Poland. Ireland also escaped the initial onslaught, only succumbing during a later episode in 1357.

Prompted by a series of climatic changes, it spread eastwards towards China and west through the armies of the Golden Horde and into Persia. By 1346 it was ravaging the armies besieging the Italian stronghold in Kaffa (modern-day Feodosia on the Black Sea coast of Crimea), who spread it to the besieged merchants by lobbing the bodies of their dead over the walls of the city: a medieval form of germ warfare. Those inside the city who were able fled on ships for destinations around the Mediterranean, carrying the plague with them: it was in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), Sicily, and Marseilles by 1347, and was attacking the papal court at Avignon by the spring of the following year. From thence, it spread along inland and sea trading routes, reaching Paris later in 1348 and making landfall at Melcombe Regis, just outside Weymouth in England, in June of that year. During the rest of 1348, and into 1349, it continued to spread north and east across the European landmass, into the lands of the Holy Roman Empire, and parts of northern Italy and the Czech Republic. It developed during the Early Middle Ages and existed through the Early Modern period. and beyond, before reaching Russia in 1351. A few lands were, in the main, spared: Finland and Iceland suffered little thanks to their small populations and minimal trade links, as did an area centred on modern-day Poland. Ireland also escaped the initial onslaught, only succumbing during a later episode in 1357.

Death and the disease

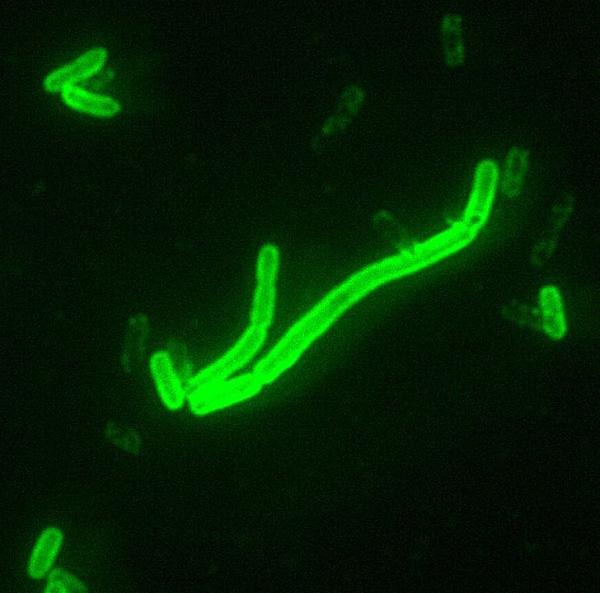

Symptoms of the bubonic plague were generally obvious, and gruesome. Infection occurred when a flea with the disease bit the person and the bacilli entered the bloodstream. The bacilli collected in the lymph nodes and began to reproduce, causing the characteristic, and exceptionally painful, swelling. A short time after, the bacilli would attack the major organs. Often, the victim would fall into a coma – although several sources refer to the victim entering a manic state – and die, typically less than a week later. Gabriele de’ Mussis, who was living in Italy during the Black Death, recorded how:

The bacilli collected in the lymph nodes and began to reproduce, causing the characteristic, and exceptionally painful, swelling. A short time after, the bacilli would attack the major organs. Often, the victim would fall into a coma – although several sources refer to the victim entering a manic state – and die, typically less than a week later. Gabriele de’ Mussis, who was living in Italy during the Black Death, recorded how:

First, out of the blue, a kind of chilly stiffness troubled their bodies. They felt a tingling sensation, as if they were being pricked by the points of arrows. The next stage was a fearsome attack which took the form of an extremely hard, solid boil. In some people this developed under the armpit and in others in the groin between the scrotum and the body. As it grew more solid, its burning heat caused the patients to fall into an acute and putrid fever, with severe headaches.

Contracting bubonic plague was not, however, necessarily fatal. Many people did survive the infection and chroniclers often attributed this to the lancing of the buboes, the pus of which giving off an awful, foetid stink. But there were two other forms of plague, both of which carried a death sentence. The first, pneumonic plague, occurred when the bacilli got into the lungs, allowing it to be spread from person to person by coughing. Onset in this case happened quickly, giving rise to the belief that it could be caught simply from looking at a plague victim, with the infected coughing up blood and struggling to breathe. Death would also come quickly – within two days – with the victim unable to absorb enough oxygen and suffering cardiac arrest. The third form, septicaemic plague, was the least common but also the fastest acting and is therefore unlikely to have played a major part in the outbreak. It happened when the bacilli reproduced quickly in the blood stream, rather than the lymph nodes, killing the victim – often when they still appeared healthy – before buboes had a chance to form.

Estimates – and they can only ever be estimates as we don’t have the necessary evidence to make anything other than a guess – of the mortality rate vary considerably, and tend to be linked to wider trends in historiography. Nor does it help that we don’t have a baseline from which to start: it is widely believed that the population peaked around 1300 and then declined somewhat thanks to a run of bad harvests and famines. But we don’t know whether the population had recovered by the time of the Black Death or whether, as Michael Postan thought, it continued to decline thanks to inherent economic and social issues. For much of the twentieth century it was believed that about a quarter to a third of the population of Europe died, although JC Russell, writing in the 1950s, put the figure as low as 20 per cent. However, in the last 30 years, this figure has been revised upwards as historians have undertaken more local research and re-evaluated their approach to the original sources, which tended to overestimate the death rate (including some that claimed that 80 or 90 per cent of the population died). Now the rate of death tends to be put at somewhere between 40 and 60 per cent, with the likes of Ole Benedictow favouring the latter.

Nor does it help that we don’t have a baseline from which to start: it is widely believed that the population peaked around 1300 and then declined somewhat thanks to a run of bad harvests and famines. But we don’t know whether the population had recovered by the time of the Black Death or whether, as Michael Postan thought, it continued to decline thanks to inherent economic and social issues. For much of the twentieth century it was believed that about a quarter to a third of the population of Europe died, although JC Russell, writing in the 1950s, put the figure as low as 20 per cent. However, in the last 30 years, this figure has been revised upwards as historians have undertaken more local research and re-evaluated their approach to the original sources, which tended to overestimate the death rate (including some that claimed that 80 or 90 per cent of the population died). Now the rate of death tends to be put at somewhere between 40 and 60 per cent, with the likes of Ole Benedictow favouring the latter.

Scapegoats and scourging: immediate reactions

Whatever the actual number of deaths, it is clear that the Black Death had a significant short-term impact on those living through it. As most people couldn’t write, we have very few letters or diaries that record the feelings of lay people. But there are a few glimpses: Petrarch, an Italian scholar who lived during the fourteenth century, provides some hint of the emotional and mental anguish of the time:

What are we to do now, brother? Now that we have lost almost everything and found no rest. When can we expect it? Where shall we look for it? Time, as they say, has slipped through our fingers. Our former hopes are buried with our friends. The year 1348 left us lonely and bereft, for it took from us wealth which could not be restored by the Indian, Caspian or Carpathian Sea. Last losses are beyond recovery, and death’s wound beyond cure. There is just one comfort: that we shall follow those who went before. I do not know how long we shall have to wait, but I know that it cannot be very long – although however short the time it will feel too long.

A huge array of preventatives and cures were tried by those awaiting, or suffering under, the Black Death. An obvious preventative was flight for those who could, or self-isolation for those left behind. City officials tried to limit movement of people, particularly strangers, and those who attended the sick could be asked to segregate themselves from society. Milan went further still, with the first three households exhibiting symptoms being walled up inside their houses and left to die, be it through sickness or starvation. Others, such as a householder in Salé, took the initiative and bricked themselves and their families in – with a supply of food and drink. Yet some threw caution to the wind and instead lived each day as if it were their last, seeking solace in companionship and drinking. They thought it best:

... to drink heavily, enjoy life to the full, go round singing and merrymaking, gratify all of one’s cravings whenever the opportunity offered, and shrug the whole thing off as one enormous joke … they would visit one tavern after another, drinking all day and night to immoderate excess; or alternatively (and this was their more frequent custom), they would do their drinking in various private houses, but only in the ones where the conversation was restricted to subjects that were pleasant or entertaining.

For others, the feeling of devastation found a release in religion. As the plague swept through Europe, rumours of its advance crept ahead. Pilgrimages increased and devout processions were ordered, vices – such as gaming and commercial pursuits on Sundays – were outlawed, and brotherhoods were formed with the purpose of looking after the sick and dead. But a few turned to a more extreme form of devotion. Flagellants appeared, ‘men and women alike, many barefoot, others wearing hairshirts or smeared with ashes. As they processed with lamentations and tears, and with loose hair, they beat themselves with cruel whips until the blood ran.’ Initially, the pope supported this bizarre spectacle but when they turned to unauthorized, and often critical, preaching they were denounced for breach of church discipline. Flagellants thereafter were threatened with public penance, excommunication, and execution; one Polish bishop even condemned a flagellant master to the stake.

Initially, the pope supported this bizarre spectacle but when they turned to unauthorized, and often critical, preaching they were denounced for breach of church discipline. Flagellants thereafter were threatened with public penance, excommunication, and execution; one Polish bishop even condemned a flagellant master to the stake.

It is, perhaps, unsurprising that anticlericalism, particularly in secular matters. rose to the surface. There is no doubt that many of the clergy remained in post and continued their work of ministering to the dying. But for many of these dedicated and honest men their reward was that they too perished. In their wake they left a gaping void. Papal licences were issued for the ordination of new priests, but they couldn’t be put to work soon enough. In such cases, ‘because priests cannot be found for love or money’, churchmen like the bishop of Bath and Wells ordered that plague victims ‘should make confession of their sins, according to the teaching of the apostle, to any lay person, even to a woman if a man is not available.’ , January 1349, in Horrox, pp. 271-2. The laity were being asked to take matters of divinity into their own hands. But even where replacements could be found they were often inexperienced and ill-educated at best; at worst, they were grasping, self-centred, and careless. They were seen as denying the very essence of their calling, as one complaint about the mendicant orders illustrates: ‘The superfluous wealth poured their way, through confessions and bequests, in such quantities that they scarcely condescended to accept oblations. Forgetful of their profession and rule, which imposed total poverty and mendicancy, they lusted after things of the world and of the flesh, not of heaven.’

, January 1349, in Horrox, pp. 271-2. The laity were being asked to take matters of divinity into their own hands. But even where replacements could be found they were often inexperienced and ill-educated at best; at worst, they were grasping, self-centred, and careless. They were seen as denying the very essence of their calling, as one complaint about the mendicant orders illustrates: ‘The superfluous wealth poured their way, through confessions and bequests, in such quantities that they scarcely condescended to accept oblations. Forgetful of their profession and rule, which imposed total poverty and mendicancy, they lusted after things of the world and of the flesh, not of heaven.’

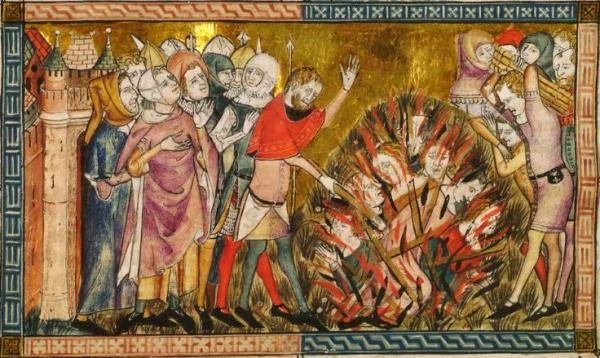

The clergy were not the only scapegoats. In some cases, foreign agents or beggars were accused of using a powdered substance to poison wells. In Narbonne, France, the unlucky ‘were torn by red hot pincers, disembowelled, their hands cut off, and then burnt’, while in Avignon ‘Many were burnt for this and are being burnt daily’. But many more people pointed the finger at the Jews, burning entire communities alive. Despite efforts made by some in authority, including Pope Clement VI, to prevent the slaughter, pleas for tolerance – or use of intelligence – largely went unheeded. Indeed, in places such as Strasbourg, attempts to protect the Jews led to the overthrow of regimes. Persecution was particularly bad in the Holy Roman Empire - one Franciscan friar boasted:

But many more people pointed the finger at the Jews, burning entire communities alive. Despite efforts made by some in authority, including Pope Clement VI, to prevent the slaughter, pleas for tolerance – or use of intelligence – largely went unheeded. Indeed, in places such as Strasbourg, attempts to protect the Jews led to the overthrow of regimes. Persecution was particularly bad in the Holy Roman Empire - one Franciscan friar boasted:

Throughout Germany, in all but a few places, they were burnt … This action was taken against the Jews in 1349, and it still continues unabated, for in a number of regions many people, noble and humble alike, have laid plans against them and their defenders which they will never abandon until the whole Jewish race has been destroyed.

A world of change

The social and political effects of the Black Death continued far beyond the immediate aftermath, not least because the plague returned several times over the next two and a half centuries: in England, there were four more major outbreaks during the remainder of the fourteenth century, and it was not until after the Great Plague of 1665 that the country had finally seen the last of it, while in France the Great Plague of Marseilles ravaged the city and surrounding area as late as 1720.

The obvious cause of social change was the fact that there were fewer people, particularly after later plagues had taken their toll. Fewer people to farm and to work led to a scarcity of labour, meaning labourers had better bargaining power so terms of employment improved. A multitude of chroniclers complained against the resultant idleness and obstinacy of the poor, who refused to pay the same rents, work the same hours for the same wages, and keep the same commitments as before. With better wages came, theoretically, more purchasing power and a better standard of living. These two improvements in the lives of working people can be seen from government reaction. The Statute of Labourers of 1351 attempted to limit the movement of workers, and their earnings, to pre-plague levels, while sumptuary legislation, first introduced in 1363, tried to outlaw ‘the outrageous excessive apparel of divers people against their estate and degree’.

The resultant social tensions were exacerbated by changes in land use. With tenants refusing to abide by the terms of their tenancy – particularly working on the lord’s land for free – and demanding money for their services, landlords were forced to put their lands out to lease. The better off peasants would lease the land, often at preferable rates, and thus begin their journey up the social ladder. Furthermore, a considerable amount of land, much of it marginal, fell out of use as demand dropped, and whole villages lay abandoned as people moved on in search of a better life. , it is likely that people were already moving away from marginal lands before the Black Death hit. As land fell vacant, it became available for purchase, leading to a greater concentration in fewer – often peasant – hands. Society thus started to reorganize along commercial, rather than feudal

, it is likely that people were already moving away from marginal lands before the Black Death hit. As land fell vacant, it became available for purchase, leading to a greater concentration in fewer – often peasant – hands. Society thus started to reorganize along commercial, rather than feudal would protect everyone, the peasants would pay for this protection by working the land, and the clergy would pray for everyone. In the secular world, the monarch was at the top of the pyramid, with each layer of nobility…, lines. It is little wonder, then, that the Peasants’ Revolt roared into being just 30 years after the Statute of Labourers with the cry of ‘When Adam delved and Eve span, who then was the gentleman?’

would protect everyone, the peasants would pay for this protection by working the land, and the clergy would pray for everyone. In the secular world, the monarch was at the top of the pyramid, with each layer of nobility…, lines. It is little wonder, then, that the Peasants’ Revolt roared into being just 30 years after the Statute of Labourers with the cry of ‘When Adam delved and Eve span, who then was the gentleman?’

The social and economic changes were the most obvious results of the Black Death and later plagues, but they weren’t the only ones. On a more subtle level, there was a shift in the way that people defined themselves and the institutions that impacted them, and the way they interacted with the world. Death, which had always been an element of life, became ever-present. Literature and art took a macabre turn, with the ‘Dance of Death’ of the skeletal Grim Reaper haunting seemingly random victims, and visions of Hell leaping from manuscript and panel. More than ever before, it taught that everybody, no matter how great during life, would end up in a grave: in the end, there is equality. Furthermore, the Black Death also taught people to question and to view choices in a different light. It showed that hallowed institutions and their representatives were fallible. It showed that the Church and the authorities were not the only source of wisdom or help. It showed that society was not set in stone and that popular pressure could make a positive difference. It did not create the Reformation, or the civil wars, or capitalism, but ultimately it did create the conditions and the mindsets in which things could change. This new way of dying hinted also at a new way of living.

Things to think about

- How great an impact did the Black Death have? How much of a long term effect did it have on society and the structures that governed it?

- What is the likelihood that the death rate was 20 per cent, or 60 per cent, and what difference would this make on our understanding of the disease and its effects?

- What do responses to the Black Death tell us about medieval societies?

- There are ongoing debates among historians about the similarities, and differences, between people of the past and us: how do you think you and your society would have reacted to the plague, and what does that say about how alike modern and medieval people are?

Things to do

- Look at late medieval art in museums, churches and other buildings: what evidence can you find of the presence of death?

- Take to Google Earth to see if you can find evidence of abandoned villages; research to discover whether those villages were abandoned as a result of the Black Death (or its resultant economic turmoil) or for a different reason.

- Individual areas often have their own folklore - still - about the Black Death, and many local museums or archaeological groups have extensive information on it. Ask around to see how the plague affected your own locality.

Further reading

Possibly the best book available on the Black Death is Rosemary Horrox's The Black Death, which is an edited volume of a wide range of primary sources in translation, together with excellent commentary. The book is so good that most other histories rely to a greater or lesser extent on what it includes.

Another approach that has been taken with some success is John Hatcher's 'eye witness' account of the effects of the Black Death on a Suffolk parish, for which there are excellent primary sources available. This is a more personal account, which tells the stories of individuals who lived through the outbreak in a semi-fictional way.