Fiasco: The Mad Tale of the Fourth Crusade

Key facts about the Fourth Crusade

- The Crusades started in the eleventh century, as an attempt to retake the 'Holy LandLands comprising of what is now Isreal and Palestine, including the holy land of the Jewish, Christian and Islamic religions.' (roughly modern-day Israel and Palestine, along with parts of Jordan, Syria and Lebanon) from the Muslim Turks.

- The Fourth Crusade was called in 1198 to bolster the Franks (the collective term for the Western Christians) in the Holy Land.

- It's target was Egypt.

- Problems financing the Crusade led to a deal being made with the Republic of Venice.

- When the crusaders couldn't pay their bills, they and the Venetians attacked two Christian cities.

- They sacked Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) and placed a new ruler on the throne.

People you need to know

- Alexios III Angelos - emperor of Byzantium who had deposed his own brother, Isaac.

- Alexios IV Angelos - son of Isaac, and later co-emperor of Byzantium.

- Enrico Dandolo - the ageing Doge of Venice (the most important government official of Venice), who came up with the financing plan for the Fourth Crusade.

- Isaac II Angelos - deposed emperor of Byzantium, father of Prince Alexios (later Alexios IV Angelos).

- Murtzuphlus - also known as Alexios V Doukas. Leader of the anti-crusader faction and, later, emperor of Byzantium.

- Geoffroy de Villehardouin - Marshall of Champagne, crusader and chronicler of the Fourth Crusade.

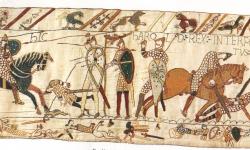

For better or worse, the Crusades were among the more spectacular, far-reaching and important endeavours of the first two millenniaThousands of years. of the Common Era. A series of campaigns and conflicts which reconstructed the geographical, political and spiritual make-up of a whole region and set of cultures in ways that are still very much felt today, they lasted for centuries and filled annals with heroes and villains, triumph and horror, glorious victories and catastrophic defeats. The greatest of them, the vast campaigns to the Holy Land that gave rise to the reputations of great chivalric heroes like Richard the Lionheart and Salah ad-Din (Saladin) still capture the imagination, but there were in fact a great number of crusades that are less well remembered. Many did not take place in the Levant at all, but within the borders of what was, or would ultimately be, Christian Europe.

In the year 1208, Pope Innocent III launched a crusade against the Christians of the Languedoc region in France, with the single mission of eradicating the Cathar 'heresyA belief or opinion that goes against the official Church doctrine.'. A popular religious movement in a region where the Church received little respect, the Cathars were to be on the receiving end of the very first explicitly authorised crusade against nominal Christians in Europe, and the results could today be identified as genocidal. Yet although this may have been the first official crusade to have been aimed at Europeans within the realms of the Catholic Church, it certainly wasn't the first time a crusading army had wound up with Christian blood on its hands.

The people of Constantinople could testify to that.

The story so far...

The Crusades had started in the final years of the eleventh century. The first trip to the Holy Land began in November 1095, with a call to arms from Pope Urban II. He was speaking in response to a plea for help from Emperor Alexios I, ruler of the Byzantine Empire, which was under pressure from the Muslim Turks. Detailing the kind of lurid images of grotesque atrocities common to medieval descriptions of ‘The Enemy’ – all torture, mangled innards, desecrations and abuse – Urban called on 'men of all ranks whatsoever, knights as well as foot soldiers, rich and poor' to head off to the Holy Land and 'exterminate' the Muslims who lived there. He topped it with the promise that religiously motivated violence would earn the warrior eternal blessings in paradise. Cited in Peter Frankopan, The First Crusade: The Call from the East (London: Vintage, 2013), p. 1-3. In addition to what was doubtless a genuine desire to retake the holy city of Jerusalem for Christians for the first time in centuries, Urban had another reason to announce the First Crusade: Europe itself was riven by violence, internal conflict and invasions, and friction between the Church authorities and powerful secularNot connected with religious matters. leaders. Giving the bellicose and fractured groups around Christendom an alien menace against which they could come together was an inspired idea and, for a short while, it worked well.

Cited in Peter Frankopan, The First Crusade: The Call from the East (London: Vintage, 2013), p. 1-3. In addition to what was doubtless a genuine desire to retake the holy city of Jerusalem for Christians for the first time in centuries, Urban had another reason to announce the First Crusade: Europe itself was riven by violence, internal conflict and invasions, and friction between the Church authorities and powerful secularNot connected with religious matters. leaders. Giving the bellicose and fractured groups around Christendom an alien menace against which they could come together was an inspired idea and, for a short while, it worked well.

Four years later, the battered and exhausted crusaders that had actually managed to survive the bloodstained journey to Jerusalem took the city and unleashed a total bloodbath, leaving few people alive. The lands of Christ regained and their job done, most crusaders headed home, leaving the Holy Land chopped up into four parts ruled by the elites who stayed – the county of Edessa, the principality of Antioch, the county of Tripoli and the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

After the initial shock of the Christian success, the forces of Islam regrouped and the Christian states found themselves under attack. A second great crusade was announced, intended to bolster the territories the Christians had captured, but it had no clear plan beyond having everybody head out to the Holy Land and take the war to the Muslims once again. It proved popular and huge numbers of restless young men answered the call. Perhaps for some of them one reason was that, by this time, the Crusader States had developed a culture and lifestyle of their own, ostentatious and lavish, completely unlike the more austere world back in the West. For an ambitious but frustrated young knight, the chance to combine holy endeavour with personal advancement was seductive. This Second Crusade was a disaster, but the Kingdom of Jerusalem did not fall and new blood had arrived to defend it.

While the Crusader States managed to hold out for a couple more decades, ultimately the forces of Islam, inspired and led by the legendary Salah ad-Din, recaptured Jerusalem and many other cities taken in 1099. Unsurprisingly, a Third CrusadeThe Third Crusade (1189-1192) was an attempt by European leaders to reconquer the Holy Land from Saladin. was called to retake what had been recaptured and the process started again. This was the famous crusade of Richard the Lionheart, whose bravery, skill and endeavour won him the respect of people on both sides of the conflict, even if he did have thousands of civilians executed after the SiegeA military operation in which enemy forces surround a town or building, cutting off essential supplies, with the aim of compelling those inside to surrender. of Acre. Although the Third Crusade did not lead to the retaking of Jerusalem, the situation for the Christians in the Levant was stabilised and the wind was taken out of Salah ad-Din's sails.

Here we go again

In 1198, eager to support the remaining fragments of the Christian Levant, Pope Innocent III – he of the Cathar slaughter – called for a Fourth Crusade to take the war back to the East, to 'fight Christ's battle and to avenge the injury done to the Crucified One'. Cited in Jonathan Phillips, The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople (London: Penguin, 2004), p.5 Once again, huge numbers of people signed up to go, although this time European monarchs were not among them. King Richard of England, hero of the Third Crusade, had been approached by papal legate Peter Capuano to front the return, who encouraged him to make peace with his rival Philip of France and focus on the greater issue in the Kingdom of Christ. Peter may well have caught Richard on a bad day as the king angrily refused and threatened to have the legate castrated. Peter left very quickly. When Richard was, rather inconveniently, killed by a crossbow bolt in the shoulder a few months later, it became clear that the papacy would need to rely on a different source of leadership. The leaders of this crusade would be lords and knights, rather than kings and princes.

Cited in Jonathan Phillips, The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople (London: Penguin, 2004), p.5 Once again, huge numbers of people signed up to go, although this time European monarchs were not among them. King Richard of England, hero of the Third Crusade, had been approached by papal legate Peter Capuano to front the return, who encouraged him to make peace with his rival Philip of France and focus on the greater issue in the Kingdom of Christ. Peter may well have caught Richard on a bad day as the king angrily refused and threatened to have the legate castrated. Peter left very quickly. When Richard was, rather inconveniently, killed by a crossbow bolt in the shoulder a few months later, it became clear that the papacy would need to rely on a different source of leadership. The leaders of this crusade would be lords and knights, rather than kings and princes.

Hallelujah – the Almighty's dollar

One of the greatest issues facing any crusade was the logistical challenge of trying to coordinate and transport a phenomenal number of men, horses and equipment to the final destination. Crusaders came from all over Christendom, spoke different languages, and often had political and territorial disputes with their fellow 'pilgrims'. Crusading also took a huge amount of money. The cash to fund such a colossal endeavour was not provided by a single sponsor, but had to be raised by the crusaders themselves. Richard the Lionheart had sold earldoms, lordships and Church offices to raise funds for his part in the Third Crusade, as well as imposing a 'Saladin Tax' on everybody in England – including the clergyThe people ordained for religious duties, especially in the Christian Church., although not, importantly, anybody who went on the Crusade with him – and requisitioned horses from every city in the land. For keen crusaders who didn't have a nation to bleed dry, the situation was much harder. One estimation suggests a knight would have to spend four times his annual income to go on crusade. Many had to turn to mortgaging or selling property and land, often to the Church.

This precarious financial reality did not simply affect individuals, it could seriously damage the chances of an expedition's success. The Fourth Crusade did not have the support of any monarchies and so had to rely even more heavily on individual crusaders to carry the financial burden, if there were to be enough warriors to retake the lands in the Levant.

To transport the huge number of troops, horses and other necessities, some leaders of the Crusade turned to the Republic of Venice. A significant maritimeConnected with the sea, especially in relation to seaborne trade or naval matters. power, the Republic was in a key position to provide the crusaders with an appropriately large fleet of ships. But it wouldn't come cheap. In April of 1201, an envoy of six representatives arrived to meet with the Doge of Venice, Enrico Dandolo. Among them was Geoffroy de Villehardouin, Marshall of Champagne, whose chronicle of the Fourth Crusade is one of the most famous, interesting and entertaining of the time.

The Doge of Venice was an old man by the time the crusaders arrived, already well into his nineties. His piety and religiosity should not be doubted, yet he was also a pragmatic, shrewd operator when necessary. He heard the pleas of the envoys and, having taken the issue to the other nobles of Venice, informed them that they would indeed build the fleet required. It would be large enough to 'carry 4,500 horses and 9,000 squires...4,500 knights and 20,000 foot sergeants.' Geoffroy de Villehardouin, in Joinville and Villehardouin trans. M.R.B.Shaw (London: Penguin Books, 1963), p.33. All of this would come with nine months’ food for the men and their horses and the Venetians would also send fifty of their own ships, on the proviso that they would keep half of any bootyValuable stolen goods, especially those seized in war. captured. It must have seemed fantastic to Villehardouin and his companions, and after a night of debating the proposal, they accepted. What they were also accepting was the price tag of 85,000 marks, a significant burden at roughly twice the annual reserves of the whole of France. If the hoped-for number of knights and soldiers did not materialise with the cash, the consequences would be severe: the crusaders would not be able to pay their bill and the Venetians would have bankrupted their whole republic in producing the fleet

Geoffroy de Villehardouin, in Joinville and Villehardouin trans. M.R.B.Shaw (London: Penguin Books, 1963), p.33. All of this would come with nine months’ food for the men and their horses and the Venetians would also send fifty of their own ships, on the proviso that they would keep half of any bootyValuable stolen goods, especially those seized in war. captured. It must have seemed fantastic to Villehardouin and his companions, and after a night of debating the proposal, they accepted. What they were also accepting was the price tag of 85,000 marks, a significant burden at roughly twice the annual reserves of the whole of France. If the hoped-for number of knights and soldiers did not materialise with the cash, the consequences would be severe: the crusaders would not be able to pay their bill and the Venetians would have bankrupted their whole republic in producing the fleet

And it all went wrong.

What Villehardouin and his fellow envoys had not bothered to consider was that while the French contingent of the crusading force may well join up in Venice, nobody else was obliged to do so. Indeed, the journey across the Alps could seem like a total waste of time even for the French, when they could just as easily depart from Marseilles or some other Mediterranean port. Unsurprisingly, when the time came for the armies to arrive in Venice, the numbers were far lower than had been estimated, as was the available money. In his chronicle, Villehardouin makes much of the negative effects of those who did not 'keep faith' and instead sailed from other ports, stating that had they done so, 'Christendom would have been exalted, and the land of the Turks brought low.' Villehardouin, Joinville and Villehardouin, pp.41-42 Perhaps this true, but it was also unfair to try and pass the buck for having made such a risky deal in the first place.

Villehardouin, Joinville and Villehardouin, pp.41-42 Perhaps this true, but it was also unfair to try and pass the buck for having made such a risky deal in the first place.

Dandolo was livid, and more than a little concerned. The Venetians had spent almost all their financial reserves on the construction of the fleet, with a whole year's work in other fields abandoned. Now the crusaders had come up short. He demanded payment and refused food for the army that sat on the little sandbar island of Lido, with the poorer soldiers suffering from hunger and boredom, their fate quite uncertain.

Yet, as Dandolo was also a practical man, he came up with – from his perspective – an ideal plan to save the day. He would persuade the embarrassed and distressed leaders of the Crusade to attack the city of Zara (modern-day Zadar in Croatia) for plunderThe violent and dishonest theft of property and possessions, to pay the remaining balance on their account as well as ensuring Venetian power in the region.

The problem was, Zara was a Christian city.

Punch thy neighbour

Zara was a wealthy city 165 miles south-east of Venice, and the Venetians had long wanted direct control. However, as well as actually being another Catholic city, it was also under the protection of the Hungarian king, Emico, a man who had taken the Cross (sworn crusader vows) himself. From the beginning of the Crusades, the property of those who journeyed to fight in the Holy Land had been under papal protection. For a crusading army to assault such a target was unthinkable. But they did it anyway.

To be sure, not everybody agreed with the idea. Villehardouin spends a good amount of time listing nobles who bailed and decided to head for the Holy Land themselves, rather than attacking fellow Christians, blaming them for their 'defection' and generally referring to them as 'trouble-makers'. Villehardouin, Joinville and Villehardouin, p.47. Among the notable lords to depart was Simon de Monfort, father of the more famous Simon who would one day die fighting Henry III and the future Edward I in England. Still, enough of the nobles did agree to the plan and so the enormous fleet set sail and, sure enough, Zara was captured and looted. The pope was understandably furious and promptly excommunicatedTo have been punished for religious crimes, such as not being allowed to participate in any Church activities. everybody involved, which meant that not only were their sins not absolved (a key boon for a crusader), but they could no longer take Mass and would be damned to Hell when they died. Envoys were sent to Rome to try and calm Innocent III and he did ultimately absolve the crusaders of their sins, but gave them a strict command to return all property taken from the Zarans and to never again attack fellow Christians unless 'another just or necessary cause should, perchance, arise'.

Villehardouin, Joinville and Villehardouin, p.47. Among the notable lords to depart was Simon de Monfort, father of the more famous Simon who would one day die fighting Henry III and the future Edward I in England. Still, enough of the nobles did agree to the plan and so the enormous fleet set sail and, sure enough, Zara was captured and looted. The pope was understandably furious and promptly excommunicatedTo have been punished for religious crimes, such as not being allowed to participate in any Church activities. everybody involved, which meant that not only were their sins not absolved (a key boon for a crusader), but they could no longer take Mass and would be damned to Hell when they died. Envoys were sent to Rome to try and calm Innocent III and he did ultimately absolve the crusaders of their sins, but gave them a strict command to return all property taken from the Zarans and to never again attack fellow Christians unless 'another just or necessary cause should, perchance, arise'. Phillips, The Fourth Crusade, p.136. This final clause was perhaps asking for trouble. The Venetians did not seem to care much anyway, as they promptly torched Zara as they left.

Phillips, The Fourth Crusade, p.136. This final clause was perhaps asking for trouble. The Venetians did not seem to care much anyway, as they promptly torched Zara as they left.

Greeks bearing (really unrealistic) gifts

As the commotion at Zara was taking place, an offer arrived from a curious and completely unexpected quarter: the crown prince of Constantinople, Alexios. In exile after his father, the Byzantine emperor, had been deposed and blinded by his own brother (another Alexios), the prince had been attempting to secure support in taking back his throne. While Pope Innocent had not expressed much interest, others suggested he might try the massive crusading army languishing in despair at Venice.

Envoys brought an offer which would give the crusaders 'the best terms...ever offered to any people'. Villehardouin, Joinville and Villehardouin, p.50. If the army of the Fourth Crusade would help Alexios take back the Byzantine throne, he would supply the phenomenal sum of 200,000 marks (more than twice the cost of the Venetian fleet), food and supplies for the entire army, 10,000 more troops for an assault on Egypt (the Crusade's intended first target) and 500 knights to stay in the Holy Land and protect it for as long as he lived. He would also place the whole of the Byzantine Empire under the religious control of Rome, something which the papacy had desired ever since the schismA split within a group caused by strongly held beliefs or opinions. that had driven the Catholic and Orthodox Churches apart. Pretty amazing, but also pretty dubious.

Villehardouin, Joinville and Villehardouin, p.50. If the army of the Fourth Crusade would help Alexios take back the Byzantine throne, he would supply the phenomenal sum of 200,000 marks (more than twice the cost of the Venetian fleet), food and supplies for the entire army, 10,000 more troops for an assault on Egypt (the Crusade's intended first target) and 500 knights to stay in the Holy Land and protect it for as long as he lived. He would also place the whole of the Byzantine Empire under the religious control of Rome, something which the papacy had desired ever since the schismA split within a group caused by strongly held beliefs or opinions. that had driven the Catholic and Orthodox Churches apart. Pretty amazing, but also pretty dubious.

Still, the crusaders were broke, and many were desperate for a way out. With the chance of the whole expedition collapsing – and with it the hope for Christian control of Jerusalem – perhaps one of Pope Innocent's ‘necessary causes’ had arisen and it would be okay for the army to divert to attack the greatest city in the Christian world. They would have to hope so.

When the leaders of the army voted on whether to accept the offer, few agreed. More and more lords refused to attack yet another, even bigger and more important, Christian city and left the army with their forces, according to Villehardouin bringing 'a great disgrace' upon themselves. Ibid., p.54. Still, the pro-attack leaders convinced enough waverers to side with them, and Alexios's offer was accepted. The fleet launched for Greece, with the smoking remains of Zara behind it.

Ibid., p.54. Still, the pro-attack leaders convinced enough waverers to side with them, and Alexios's offer was accepted. The fleet launched for Greece, with the smoking remains of Zara behind it.

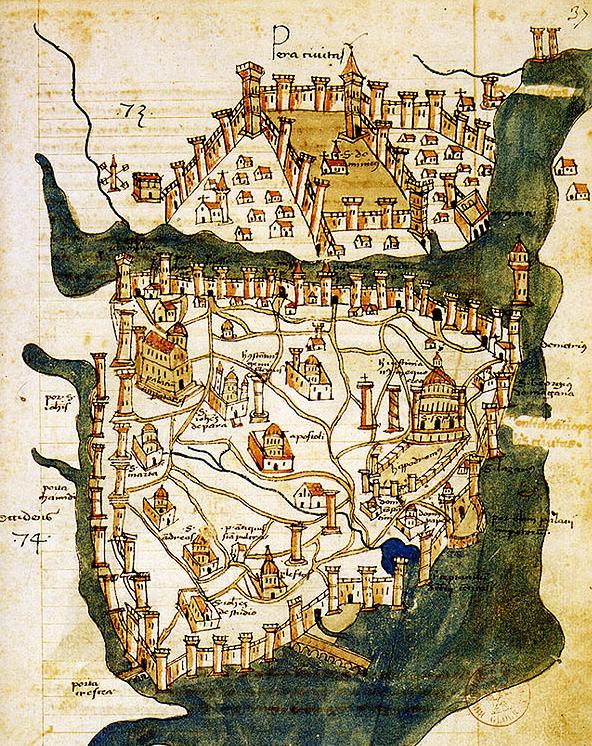

The Queen of Cities

Constantinople was truly the greatest city in the Christian world. Home to as many as 400,000 people, surrounded by vast rings of walls and decorated with numerous palaces and hundreds of churches, it well deserved the awe with which the crusaders reacted when first they saw it. Even given his fondness for explosions of superlatives, Villehardouin captured the feelings of many when he stated that the idea of assaulting such a place was intimidating, 'for never had so grand an enterprise been carried out by any people since the creation of the world'. Villehardouin, Joinville and Villehardouin, p.59. Constantinople was exceedingly well defended, and it needed to be. At the centre of the Byzantine Empire, it frequently had to see off attacks from all sides and from many different foes. Most important of these was in the East, where the Muslim Turks had taken more and more land from the emperor’s control. As a large military power on the front lines in the great cultural and religious struggle, the Byzantine Empire was a bulwark, protecting the rest of Christendom.

Villehardouin, Joinville and Villehardouin, p.59. Constantinople was exceedingly well defended, and it needed to be. At the centre of the Byzantine Empire, it frequently had to see off attacks from all sides and from many different foes. Most important of these was in the East, where the Muslim Turks had taken more and more land from the emperor’s control. As a large military power on the front lines in the great cultural and religious struggle, the Byzantine Empire was a bulwark, protecting the rest of Christendom.

Yet relations between Byzantium and the rest of Europe were not always easy. The Byzantines were scapegoated after the disaster of the Second Crusade, blamed for having been too sympathetic to Islam and for having betrayed the crusaders through double-dealing and lack of support. This, combined with a great cultural and religious divide, meant the Byzantines were just as mistrusting of the Western Europeans as they were mistrusted by them. Now a huge fleet of ships from the West had arrived on their doorstep.

While the leaders of the Crusade hoped that the city’s population would welcome their exiled prince with open arms, they were also aware that war was the most likely outcome. Despite the intimidating nature of the city, the crusaders did have a chance: although Constantinople had never once fallen to a conqueror, the defences were in a state of disrepair and what had once been a powerful imperial navy had shrunk in scale significantly. Furthermore, Prince Alexios's usurping uncle, Alexios III, had not prepared for the arrival of the Western force. No new ships had been built, the necessary timber supplies having been refused because the forests surrounding the city were reserved for imperial hunts. This is not to say that an attack on the city would be a walkover: the Byzantines had formidable ground forces, made up of both natives and foreign mercenaries. The most impressive group among these outsiders was the Varangian Guard, made up mainly of fierce Scandinavians, famous for their huge battle-axes.

Emperor Alexios III acted first to try and resolve the situation. He offered food and money to the crusaders, who had limited supplies, in exchange for them going away. The crusaders, in their turn, offered him money allowing him to live in luxury, but only if he submitted to Prince Alexios. As an attempt to push this idea, Dandolo suggested parading the prince before his people to rouse their support. Unfortunately, nobody came out in support of him. If the gates did not open and Alexios could not take his throne, there would be no money, no extra ships, no provisions, no more warriors, and no journey to Egypt – the point of the Fourth Crusade in the first place.

On 5 July 1203, the first siege of Constantinople began with a daring amphibious assault, galleys piling in towards the shore, pulling with them smaller landing boats. At the sight of the armoured crusading knights leaping from the boats with their swords, horses being landed beside them, Alexios III and his forces turned tail and ran, leaving behind plenty of booty for the marauding Westerners. The following morning the Byzantines attempted a similar method of attack, sending troops on barges to join those coming from the Galata Tower, a defensive position which protected one end of the great chain that blocked entry to the Golden Horn, Constantinople's natural harbour. The attack was fought back and the crusaders pressed their advantage, taking the tower and opening the Golden Horn to the fleet.

The fighting went on tit-for-tat for many days until at last the Venetians scaled the walls using ladders from their ships, broke through and secured a foothold in the city itself. Faced with large numbers of defending troops, they lit a fire which spread through the nearby buildings. The emperor did attempt further attacks but, to the general astonishment of his citizens, he eventually snuck off with as much gold as he could carry. Somewhat miffed, and doubtless a little unsure of what to do, the Byzantines went down to the dungeons, brought the blinded ex-emperor, Isaac, back up and reinstalled him on his throne. He sent a message out to his son and told him the good news. The siege was over. The crusaders must have been feeling very happy.

Payday?

Shortly after the restorationThe restoration of the monarchy and the return to a pre-civil war form of government in 1660, following the collapse of the Protectorate. of Isaac, Prince Alexios was welcomed back to the city and installed as co-emperor, Alexios IV. Persuaded that the citizens of Constantinople would not be happy with enemy forces camped directly on their doorstep, the crusaders moved their army across the Golden Horn. There they set up camp and waited for the return on their investment. As they did, many wrote back to Western Europe, celebrating their success which was, clearly, a gift from God. One man, Hugh of Saint-Pol, wrote with excitement of the Byzantine Empire's reunification with the Roman Pontiff and how it acknowledged itself 'to be the daughter of the Roman Church.' Cited in Phillips, The Fourth Crusade, p.195. Which was rubbish. This was not the fourth century and Alexios was not Constantine the Great, who had first – nominally – converted the Roman Empire to Christianity. The idea that the Orthodox Church and its devotees would suddenly agree to subjugation was wildly unrealistic.

Cited in Phillips, The Fourth Crusade, p.195. Which was rubbish. This was not the fourth century and Alexios was not Constantine the Great, who had first – nominally – converted the Roman Empire to Christianity. The idea that the Orthodox Church and its devotees would suddenly agree to subjugation was wildly unrealistic.

Of more pressing concern was money. The crusaders had assaulted Zara to pay their debts and still wound up dead broke. They had conquered the greatest city in Christendom for the promise of, among other things, a huge amount of cash. It was time for Alexios to pay up. In their attempt to do so, Isaac and Alexios resorted to extreme measures, demanding contributions from citizens as well as, unbelievably, raiding churches and cathedrals across the city for treasures that could be melted down and handed over. In the words of Niketas Choniates, Greek chronicler and steadfast critic of both the emperor and the Westerners, they 'touched the untouchable...holy icons of Christ consigned to the flames after being hacked to pieces with axes.' Niketas Choniates, O City of Byzantium: Annals of Niketas Choniates, trans. H. J. Magoulias (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1984) p.302.

Niketas Choniates, O City of Byzantium: Annals of Niketas Choniates, trans. H. J. Magoulias (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1984) p.302.

The people of Constantinople were appalled, not least because it had been made possible by the huge army of crusaders still parked across the harbour. The crusaders themselves were not oblivious to this fact and so it came as no surprise when Alexios visited them and told them – in one of history's great understatements – 'I should like you to know that a number of my people do not love me' and 'the Greeks as a whole are full of resentment because it is by your help that I have regained my empire.' Villehardouin, Joinville and Villehardouin, pp.76-77.

Villehardouin, Joinville and Villehardouin, pp.76-77.

Alexios needed more time to secure himself in his position, and so one part of the army remained near the city while the other set off with him on a journey around his empire, to meet the populace, get their obedience and fight anybody who might oppose him. The trip took some time, but ultimately went well: although the army did not cover all parts of the empire, it secured the obedience of important areas. Alexios headed home feeling pleased. He was less pleased to find that a large part of Constantinople had burned down while he was away.

Whoever started it, a fight between Byzantines and Westerners resulted, yet again, in somebody torching some buildings. This time the fire went completely out of control. It roared across the city, burning thousands of homes and churches, even threatening the majestic cathedral of Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom), one of the city's most famous and glorious buildings. By the time the fire was extinguished, it had ripped a huge strip right through the city, leaving more than four hundred acres of land a charred mess.

The blaze had not just taken lives and homes, it had heated the hatred of the Byzantines for the crusaders to boiling point. As their key supporter, Alexios was strongly criticised and pressure was put on him to stop bleeding the city dry to pay his debts. The flow of money and supplies to the army camped across the Golden Horn slowed, then stopped. A group of representatives from the army arrived in the imperial palace to demand the supplies be restored, but left in fear of their lives as the rage of the locals exploded forth at last.

War started again. Although the Greeks had the worst of the engagements, the Westerners suffered as well. An audacious attempt to burn the Venetian fleet with fire ships was unsuccessful, but could have been a major victory for the Byzantines. With their backs against the wall, the people of Constantinople needed greater leadership than Alexios or his feeble, blind father could give. Step forward Murtzuphlus, a leader of the anti-crusader party and a man with a firmer hand than either emperor. Snatching the helpless Alexios in the middle of the night, he had him thrown in the dungeons. Isaac died shortly thereafter, apparently after being 'overcome with fear'. Then Murtzuphlus, now installed as emperor, had Alexios unsuccessfully poisoned. When the young emperor refused to die, Murtzuphlus took matters into his own hands and strangled him to death.

In spite of the trouble between them, Alexios had been the only real connection between the Westerners and Byzantium. Now that tie had been well and truly cut. Nobody was going to give the crusaders anything. If they weren't to return home in utter shame, there was only one course open to them and it was the capture and sack of Constantinople.

The Queen weeps

After months of preparation on both sides, the desperate forces of the Fourth Crusade launched their assault on Constantinople in April 1204. They immediately found themselves in trouble. The massive fire of the previous year had left a healthy amount of rubble in the city and the Byzantines collected boulders to use against the knights and siege engines that were coming at them. Added to that, the wind began blowing against the crusaders, so their ships were unable to get near the shore to mount an effective attack. The Byzantines were delighted and took to the walls, jeering; some even took the opportunity to moon their opponents.

The rank and file of the crusader army were demoralised, but were persuaded that the troubles were a test, rather than a condemnation, from God. Faith and righteous suffering would see them through. Sure enough, on 12 April, the wind changed. The crusaders were now at an advantage and sailed their ships right to the walls of the great city. While the battle-axes of the Varangian Guard swung in the air, the Venetians made it to the top and, with much blood and sweat, broke through and flew their flags alongside those of their French comrades from the walls of Constantinople. As Alexios III had before him, Murtzuphlus upped and ran. The Byzantines had lost three emperors in less than two years.

The Queen of Cities had fallen, and all that was left was for her to have her dignity violated. The crusaders dutifully obliged, ransacking and burning the city for days, stealing everything they could find, be it money, jewels or holy relicsParts of a deceased holy person's body or belongings kept as an object of reverence, or something from an earlier time.. The most famous of all the pilfered treasures were the four great bronze horses, nearly a thousand years old, that were stolen by the Venetians and taken home. They still decorate St Mark's Basilica in Venice today.

Every new fiasco starts with some other fiasco's end

Murtzuphlus didn't survive long. He was caught, blinded (as usual) and thrown to his death from the top of a column. By this time, Byzantium had a new emperor, but for the first time in its long history, it was not a Greek. Baldwin of FlandersThe modern area of northern Belgium and historically a territory in the Low Countries., one of the leaders of the Fourth Crusade, had been installed as Constantinople's first Latin emperor, Baldwin I.

The crusaders who had set out so full of optimismHopefulness and confidence about the future or the success of something. years earlier had hoped to reclaim the Kingdom of Christ for the Christians. Instead they had invaded, raided and burned two great Christian cities, fractured their own alliance and torn apart the greatest empire in the West. They would spend decades struggling against outsiders to hold on to gains they should never have had in the first place.

And they never made it to Egypt.

Things to think about

- What was the point of crusading?

- Were there any benefits to crusading, for either side?

- Was the Fourth Crusade always doomed to fail, and was it, indeed, a failure?

- Could the Fourth Crusade's actions ever be justified?

- What does the Fourth Crusade tell us about politics and society in Christendom at the beginning of the thirteenth century?

- How does the Fourth Crusade reflect the divisions between Orthodox and Catholic Christianity?

Things to do

- For those lucky enough to be able to travel, Istanbul should be the first stop on anyone's itinerary if they want to find out more about the Fourth Crusade. The official tourist website is here.

- Slightly closer to home, the four stolen horses can still be found outside St Mark's Basilica in Venice. Furthermore, Venice is a fantastic city to visit to appreciate the culture, wealth, grandeur, politics and trade of one of the most important states in medieval and early modern Europe. The official tourist website is here.

- In Britain, many museums - such as the British Museum - hold artefactsObjects made by humans that are of historical interest. from the Byzantine Empire and the Crusades. Many are free to enter, and none will cost as much to visit!

- There are several primary sources of the Fourth Crusade that are available for free online. Some can be found here.

- In the Middle Ages, planning a long journey was no easy task. The British Library has an array of interesting articles on the state of medieval mapping - try starting here. While this map contains errors, it will also give readers an idea of the state of trade routes at the time of the Fourth Crusade.

- There is a brilliant project that uses computer imaging to reconstruct Constantinople around the year 1200. It can be found here.

Further reading

A good look at the whole history of the Crusades, including plenty of smaller ones, is Crusaders by Dan Jones. In entertaining and readable style, it is a fantastic primer for further reading.

For a look at the beginnings of crusading and the First Crusade in particular, Peter Frankopan's The First Crusade: The Call From the East is excellent. Focusing on the role of the Byzantine Empire in the Crusade, it makes for fascinating reading.

An excellent book on the Fourth Crusade itself is The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople by Jonathan Phillips. It explores the whole story of the Crusade in great detail and is written in an engaging and entertaining style.

Villehardouin's chronicle of the Fourth Crusade is easily accessible in English translation as part of the book Joinville and Villehardouin.

Cover image: miniature in a manuscript of 9 La Conquête de Constantinople by Geoffreoy de Villehardouin, Venetian ms., c. 1330.

- Log in to post comments