Harold Harefoot

Key facts about Harold Harefoot

- Harold Harefoot was king of England between 1035 (officially 1037) and 1040.

- He was the son of the previous king of England, Cnut, but had a half-brother who also claimed the throne.

- He made an enemy of Emma of Normandy, who was trying to keep the throne of England for her own son, and accidentally killed one of her other sons.

- Very little else is known about him.

People you need to know

- Ælfwine - possibly Harold Harefoot's son

- Æthelnoth – Archbishop of Canterbury

- Æthelred the Unready – king of England from 978 until 1016. First husband of Emma of Normandy and father of Alfred Ætheling and Edward the Confessor.

- Alfred Ætheling – exiled son of Emma of Normandy and Æthelred the Unready

- Cnut – (or Canute) Danish king of England from 1017 until 1035. Married first to Ælfgifu of Northampton and then to Emma of Normandy. Father of Svein Knutsson, Harold Harefoot and Harthacnut.

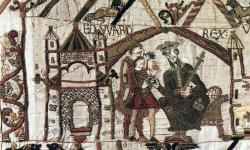

- Edward the Confessor - son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy. King from 1042 until 1066.

- Harold Harefoot – king of England between 1035 and 1040, son of Cnut and Ælfgifu of Northampton

- Harthacnut – son of Cnut and Emma of Normandy. King of England from 1040 until 1042.

- Svein Knutsson – eldest son of Cnut and Ælfgifu of Northampton

- Emma of Normandy – wife of Æthelred the Unready and then of Cnut. She had Alfred Ætheling and Edward the Confessor by her first marriage and Harthacnut by her second.

- Ælfgifu of Northampton – Cnut's first wife (or concubine), and mother of Svein Knutsson and Harold Harefoot.

Harold Harefoot is 'one of the most faceless kings ever to have ruled England.'  Marc Morris, Harold Harefoot, written on 17 March 2014, accessed on 17 March 2016, http://www.marcmorris.org.uk/2014/03/harold-harefoot.html Harold ruled briefly from 1035 until 1040, and what has been recorded is often based as much on rumour, judgement and supposition as it is on fact. There are only two events of his short reign that are known in any detail: his 'seizure' of power on the death of his father, and the blinding and subsequent death of his step-brother, Alfred Ætheling, following a possible invasion attempt. Even the reports of these are shrouded in mystery and bias.

Marc Morris, Harold Harefoot, written on 17 March 2014, accessed on 17 March 2016, http://www.marcmorris.org.uk/2014/03/harold-harefoot.html Harold ruled briefly from 1035 until 1040, and what has been recorded is often based as much on rumour, judgement and supposition as it is on fact. There are only two events of his short reign that are known in any detail: his 'seizure' of power on the death of his father, and the blinding and subsequent death of his step-brother, Alfred Ætheling, following a possible invasion attempt. Even the reports of these are shrouded in mystery and bias.

So what do we know about him? Despite being considered an Anglo-Saxon king he was Danish. He was however more English than the other contender for the throne, Harthacnut, who was half Danish and half Norman. He was Cnut's son through Cnut's first wife Ælfgifu of Northampton (whom Cnut never divorced, despite marrying Æthelred the Unready's widow, Emma of Normandy). However, even his parentage isn't certain. Some claimed that Ælfgifu wasn't even Cnut’s wife, but his concubine, which could explain the lack of any evidence for a divorce. Yet, it was not unknown for kings of Norse descent to take more than one wife and for certain pagan customs, such as marriage rites, to be practised alongside Christian ones. As Tom Holland says, 'In lands where the Northmen had become Christians, princes were generally content to satisfy themselves with two [wives]…the practice brought Canute too many advantages for him to contemplate abandoning it.'

He was however more English than the other contender for the throne, Harthacnut, who was half Danish and half Norman. He was Cnut's son through Cnut's first wife Ælfgifu of Northampton (whom Cnut never divorced, despite marrying Æthelred the Unready's widow, Emma of Normandy). However, even his parentage isn't certain. Some claimed that Ælfgifu wasn't even Cnut’s wife, but his concubine, which could explain the lack of any evidence for a divorce. Yet, it was not unknown for kings of Norse descent to take more than one wife and for certain pagan customs, such as marriage rites, to be practised alongside Christian ones. As Tom Holland says, 'In lands where the Northmen had become Christians, princes were generally content to satisfy themselves with two [wives]…the practice brought Canute too many advantages for him to contemplate abandoning it.' Tom Holland, Millennium: The End of the World and the Forging of Christendom London: Abacus, (2007) p.287 It was also rumoured that Harefoot was a changeling (the son of a cobbler who had been sneaked into Ælfgifu's bed), as put about by a desperate Emma of Normandy attempting to protect her own son's inheritance.

Tom Holland, Millennium: The End of the World and the Forging of Christendom London: Abacus, (2007) p.287 It was also rumoured that Harefoot was a changeling (the son of a cobbler who had been sneaked into Ælfgifu's bed), as put about by a desperate Emma of Normandy attempting to protect her own son's inheritance.

Seizure of power

Harefoot's father, and king of England, Cnut, died unexpectedly in 1035, without seeming to have made much provision for the rule of the kingdom thereafter. Harefoot's elder brother, Svein, was with his mother in Norway, ruling there. His half-brother, Harthacnut, was securing lands in Denmark, leaving just Harefoot, and his step-mother Emma of Normandy, in England. Emma immediately tried to claim England for her son, Harthacnut, based on the alleged promise Cnut made to Emma that he would 'never set up the son of any other woman to rule after him'. Encomium Emmae Reginae, 2.16 The WitangemotAn Anglo-Saxon council of elders, literally translated as 'council of the wise'.An Anglo-Saxon council of elders, literally translated as 'council of the wise'. , meeting at Oxford, promptly split into two factions, and a compromise was reached. Harold became protector of England for himself and his absent brother, with Emma holding WessexAn Anglo-Saxon kingdom in the south of England, and a noble house. After Anglo-Saxon times, the term has been used to refer to the south west of England (excluding Cornwall).An Anglo-Saxon kingdom in the south of England, and a noble house. After Anglo-Saxon times, the term has been used to refer to the south west of England (excluding Cornwall).An Anglo-Saxon kingdom in the south of England, and a noble house. After Anglo-Saxon times, the term has been used to refer to the south west of England (excluding Cornwall). for Harthacnut. That he was not recognised as sole king was reinforced by Æthelnoth, the Archbishop of Canterbury, who refused to perform a coronationThe ceremony of crowning a king or queen (and their consort).The ceremony of crowning a king or queen (and their consort).The ceremony of crowning a king or queen (and their consort). ceremony with any royal regalia. Harefoot, it is said, rejected Christianity in protest, and refused to attend any services until he was crowned.

Encomium Emmae Reginae, 2.16 The WitangemotAn Anglo-Saxon council of elders, literally translated as 'council of the wise'.An Anglo-Saxon council of elders, literally translated as 'council of the wise'. , meeting at Oxford, promptly split into two factions, and a compromise was reached. Harold became protector of England for himself and his absent brother, with Emma holding WessexAn Anglo-Saxon kingdom in the south of England, and a noble house. After Anglo-Saxon times, the term has been used to refer to the south west of England (excluding Cornwall).An Anglo-Saxon kingdom in the south of England, and a noble house. After Anglo-Saxon times, the term has been used to refer to the south west of England (excluding Cornwall).An Anglo-Saxon kingdom in the south of England, and a noble house. After Anglo-Saxon times, the term has been used to refer to the south west of England (excluding Cornwall). for Harthacnut. That he was not recognised as sole king was reinforced by Æthelnoth, the Archbishop of Canterbury, who refused to perform a coronationThe ceremony of crowning a king or queen (and their consort).The ceremony of crowning a king or queen (and their consort).The ceremony of crowning a king or queen (and their consort). ceremony with any royal regalia. Harefoot, it is said, rejected Christianity in protest, and refused to attend any services until he was crowned.

Emma camped out in Winchester, in the Wessex heartlands, and awaited the return of her son. But as Harthacnut delayed his return more power shifted into the hands of Harefoot. In desperation, Emma contacted her two exiled sons, whom she hadn't seen for 20 years, and asked them to help her. Both responded: Edward, the future king, landed somewhere near Southampton but was repelled and retreated back to Normandy. Her other son had more success in landing. He was met at Dover by Earl Godwin, who wined and dined him so well that he was sleeping like a baby when Godwin's men first attacked, killing his guard and blinding him. Alfred was left in the care of the monks of Ely, but his wounds were too severe and he soon died of them. Emma was exiled from England and sought refuge in FlandersThe modern area of northern Belgium and historically a territory in the Low Countries.The modern area of northern Belgium and historically a territory in the Low CountriesA region in western Europe which includes Belgium and the Netherlands..The modern area of northern Belgium and historically a territory in the Low CountriesA region in western Europe which includes Belgium and the Netherlands... Emma thereafter spread the rumour that Harefoot had forged the letters and her seal in order to entrap her sons, although this is generally not believed, including by Edward, who avoided his mother where possible. By 1037, Harold Harefoot was recognised as sole king.

Emma thereafter spread the rumour that Harefoot had forged the letters and her seal in order to entrap her sons, although this is generally not believed, including by Edward, who avoided his mother where possible. By 1037, Harold Harefoot was recognised as sole king.

Harold's reign

Apart from that mentioned above, very little is known about Harold, the man or his reign. After a somewhat rocky start and Emma's exile we know he was unchallenged as king, suggesting that he was at least in part successful. Part of his success has been put down to the skilful manipulation, begging and bribing of Harthacnut's supporters by Ælfgifu, whom some have said to have been the real power behind the throne. This could be why Godwin switched sides, from Harthacnut to Harold. His nickname has been one 'fact' considered definite about Harefoot, and many have taken it to mean that he was fast and a good hunter. But the first time it was used was a century after his death and seems to be nothing more than a monk's confusion between him and the first Norwegian king Harald Fairhair. Neither is any offspring of his certain. We think Harold may have married and possibly had a son called Ælfwine, who later became a monk and is recorded as being the son of 'Harold, who was king of the English People'. However, the question then is why did he not have a claim to the throne? Perhaps he was illegitimateIn terms of children, those born out of wedlock (to unmarried parents).In terms of children, those born out of wedlock (to unmarried parents).In terms of children, those born out of wedlock (to unmarried parents)., or too young to compete with Harthacnut. Perhaps it had already been agreed that on Harold's death the throne would pass to his half-brother. Or perhaps Ælfwine was not his son.

This could be why Godwin switched sides, from Harthacnut to Harold. His nickname has been one 'fact' considered definite about Harefoot, and many have taken it to mean that he was fast and a good hunter. But the first time it was used was a century after his death and seems to be nothing more than a monk's confusion between him and the first Norwegian king Harald Fairhair. Neither is any offspring of his certain. We think Harold may have married and possibly had a son called Ælfwine, who later became a monk and is recorded as being the son of 'Harold, who was king of the English People'. However, the question then is why did he not have a claim to the throne? Perhaps he was illegitimateIn terms of children, those born out of wedlock (to unmarried parents).In terms of children, those born out of wedlock (to unmarried parents).In terms of children, those born out of wedlock (to unmarried parents)., or too young to compete with Harthacnut. Perhaps it had already been agreed that on Harold's death the throne would pass to his half-brother. Or perhaps Ælfwine was not his son.

Harold's death

Harold Harefoot died on 17 March 1040, just five years after his father. No-one is sure of the cause, although the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle attributes it to divine judgement. There is a possibility there was some congenital defect that caused the deaths of a number of young kings, although this is based primarily on conjecture. Harefoot was buried in Westminster but Harthacnut, eventually landing in England to claim his inheritance, had Harefoot's body dug up, beheaded, dragged through a sewer and dumped into the Thames. It was recovered by some fishermen and reburied either in St Clement Danes Church in London or Morstr (an unknown and now lost place).

Things to think about

- What do we actually know about Harold Harefoot?

- How biased are the sources, and why are they biased?

- Was Harefoot an illegitimate child?

- Was his claiming the throne fair?

Things to do

- Although the original church has been rebuilt several times, the possible final resting place of Harold Harefoot can still be visited. More information on the church can be found here.

Further reading

Very little has been written about Harold Harefoot or his successors. The best sources of information are included in other books, such as Michael Wood's In Search of the Dark Ages.

- Log in to post comments