Appeasement: An Introduction

Key facts about appeasement

- Appeasement was the process by which Britain and France tried to come to peaceful terms with Hitler in the run-up to the Second World WarA global war that lasted from 1939 until 1945..

- Hitler made a series of demands for rearmament and land during the 1930s that constantly increased in scale.

- Some of his demands initially seemed reasonable.

- Britain was scared about entering into another war with Germany because of memories and the cost of the First World War and because it felt it wasn't ready for another war.

- Austria and Czechoslovakia had both ceased to exist independently before Britain realized that Hitler would never be satisfied.

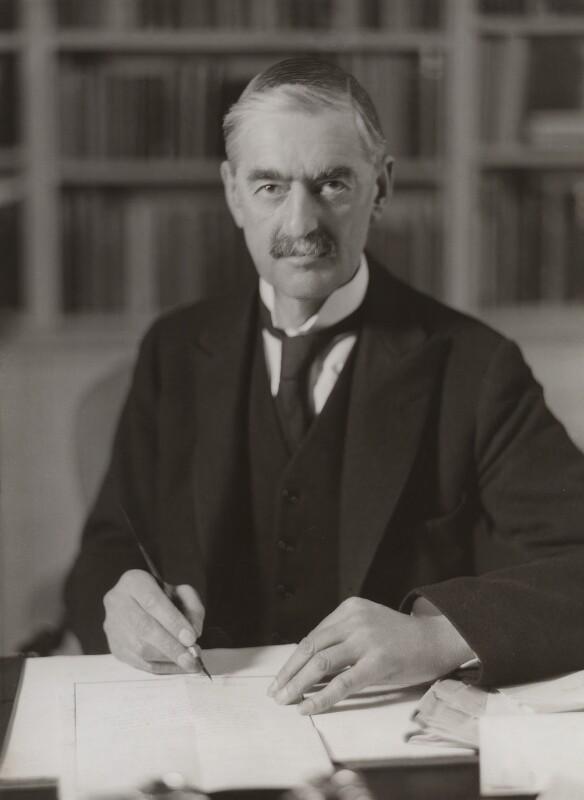

- Britain, especially the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, relied on the assumption that Hitler was an honourable man who could be trusted.

- Some people didn't trust Hitler from the start and warned about appeasement.

- There is an argument that if the policy of appeasement had not been pursued, then the scale of the Second World War would have been much smaller - if it had happened at all.

People you need to know

- Edvard Beneš - president of Czechoslovakia from 1935 to 1938.

- Neville Chamberlain - British prime minister from 1937 until 1940, and main proponent of the policy of appeasement.

- Winston Churchill - Chamberlain's replacement as prime minister in 1940, and loudest opponent of appeasement.

- Édouard Daladier - First World War veteran and prime minister of France from 1938 to 1940.

- Emil Hácha - Beneš's replacement as president of Czechoslovakia, and from 1939 nominal president of the German ProtectorateThe position or period of office of a Protector, especially that of Oliver and Richard Cromwell in England. of Bohemia and Moravia (within the Greater German Reich).

- Adolf Hitler - German chancellor from 1933, and Führer ('leader') of Germany from 1934 until 1945. Possibly the most reviled man in recent history.

- Joachim von Ribbentrop - German ambassador to the United Kingdom from 1936 to 1938, and German foreign minister from 1938 until 1945. He was later executed following his trial at Nuremberg.

- Kurt von Schuschnigg - chancellor of Austria from 1934 until 1938.

Just twenty years after the War to End All Wars, on 3 September 1939 Britain was once again at war with Germany. With hindsight – and, indeed, to a few contemporaries – a second conflagration had seemed inevitable. Regardless of whether the French Marshal Foch really did call the Versailles TreatyThe Versailles Treaty was the peace treaty signed at the end of the First World War. In reality, it was especially harsh towards Germany and has been called 'the twenty-year truce'. ‘an ArmisticeAn agreement made by opposing sides in a war to stop fighting. for twenty years’, The likelihood is that he didn’t, at least not in 1919. the fact was that Europe was unstable between the two world wars, with new frontiers, new politics, new and vast economic problems, and countries left reeling from the shock of 1914-1918. The optimists hoped that the horrible memories of the Great War would be enough to pacify the continent forever, and during the economic boom of the mid-1920s it seemed that Europe had started to find a new way to live in harmony. But once Hitler became German chancellor in 1933 and almost immediately overturned the fledgling democracy of the Weimar RepublicThe unofficial name for the German state between 1919 and 1933. along with many of the treaties that guaranteed peace, could Britain and France ever have doubted that Nazi Germany was desperate to renew the fight? Did they, in fact, sleepwalk into a worldwide conflagration that could have been avoided, if only they had acted in time?

The likelihood is that he didn’t, at least not in 1919. the fact was that Europe was unstable between the two world wars, with new frontiers, new politics, new and vast economic problems, and countries left reeling from the shock of 1914-1918. The optimists hoped that the horrible memories of the Great War would be enough to pacify the continent forever, and during the economic boom of the mid-1920s it seemed that Europe had started to find a new way to live in harmony. But once Hitler became German chancellor in 1933 and almost immediately overturned the fledgling democracy of the Weimar RepublicThe unofficial name for the German state between 1919 and 1933. along with many of the treaties that guaranteed peace, could Britain and France ever have doubted that Nazi Germany was desperate to renew the fight? Did they, in fact, sleepwalk into a worldwide conflagration that could have been avoided, if only they had acted in time?

All’s fair in love and war

The Versailles Treaty of 1919 was not the ‘fairest’ of treaties: it was punitive and sought vengeance on Germany and her allies for inflicting a devastating war on much of Europe in the preceding years. Germany, burdened with harsh reparation payments, was allowed only a token military, and lost land, people and industry to its newly invented neighbours and old enemies. Perhaps what was even more psychologically damaging was Article 231, the ‘war guilt clause’, which stated that:

… Germany accepts the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies.

It is hardly surprising, then, that once Hitler started overturning elements of the treaty, many in Britain shrugged their shoulders. The Versailles Treaty had created a monster. Now, the only way to tame the beast was to remove or adapt those issues that had brought it into existence. Remilitarization, to put Germany on a par with other European countries, was inevitable, and France and America were already making tidy profits off clandestine deals. With lucrative potential markets slipping away, Britain also took steps to accommodate her long-time allyA state (or person) that is formally working with another state (or person), usually confirmed by a treaty or other official agreement. and erstwhile enemy, agreeing in 1935 to an Anglo-German Naval Agreement that allowed Germany to increase her navy to 35 per cent of the size of Britain’s enormous fleet – and which thereby broke the Versailles Treaty.

The Rhineland

The lack of Allied resolve – and, indeed, the active collaboration – in the face of German defiance of treaties encouraged Hitler to gamble, often against the advice of his military, and to push further. The Versailles Treaty, backed by subsequent agreements such as the Locarno Pact of 1925, had established a demilitarized zone along Germany’s western borders, designed to reassure her neighbours and protect against future German aggression. Germany, however, saw France’s ability to build up troops along its defenceless border as not only unbalanced but absolutely detrimental to the health of the nation. It was an outward reflection of the subservience inflicted upon Germany by the victors of the First World War.

So, on 7 March 1936, Germany began the military reoccupation of the Rhineland. In the space of a day, 22,000 troops entered the demilitarized zone, bolstered by several police divisions to give the impression that German forces were larger than they actually were. The excuse was the bilateral Franco-Soviet Treaty of Mutual Assistance, which aimed to offer a level of comfort and security between the two nations against any future moves made by Germany. This, Hitler claimed, threatened Germany’s ability to defend herself, effectively turning Germany from aggressor to victim.

Instead of immediate and decisive action from Britain and France – or the increasingly toothless League of Nations (that had been established in 1920 as an international peacekeeper and from which Hitler had withdrawn in 1933) – the Allies dithered. There was some justification in Germany reclaiming full sovereignty in her own country, as well as in ensuring her ability to protect herself. Britain therefore discouraged France from taking any action – there was no need to risk war to prevent Germany from walking into her own ‘back garden’. J. Noakes and G. Pridham (eds), Nazism, Vol. III (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2001), p. 61. What’s more, with the reoccupation of the Rhineland came a number of hints from Germany: that she would be willing to be tied to new non-aggression treaties, that she would enter into a contract to keep the size of her air force small (even though Versailles denied her an air force altogether), that she would consider rejoining the League. These promises were so enticing that, as the Daily Telegraph reported less than a week later, ‘Britain is satisfied that Germany does not contemplate any aggressive act in the measures she has now taken.’

J. Noakes and G. Pridham (eds), Nazism, Vol. III (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2001), p. 61. What’s more, with the reoccupation of the Rhineland came a number of hints from Germany: that she would be willing to be tied to new non-aggression treaties, that she would enter into a contract to keep the size of her air force small (even though Versailles denied her an air force altogether), that she would consider rejoining the League. These promises were so enticing that, as the Daily Telegraph reported less than a week later, ‘Britain is satisfied that Germany does not contemplate any aggressive act in the measures she has now taken.’ Daily Telegraph, 13 March 1936.

Daily Telegraph, 13 March 1936.

Hitler, however, saw things differently. As the architect and later member of Hitler’s Cabinet Albert Speer recalled:

From this Hitler concluded that both England and France were loath to take any risks and anxious to avoid any danger. Actions of his which later seemed reckless followed directly from such observations. The Western governments had, as he commented at the time, proved themselves weak and indecisive… [L]ater, when he was waging war against almost the entire world, he always termed the remilitarization of the Rhineland the most daring of all his undertakings. “We had no army worth mentioning; at that time it would not even have had the fighting strength to maintain itself against the Poles. If the French had taken any action, we would have been easily defeated; our resistance would have been over in a few days.”

Albert Speer, Inside the Third ReichLiterally meaning the third realm or empire. It is the name used to describe Nazi Germany, from 1933 until 1945. (London: Phoenix, 1970), pp. 117-8.

‘Peace with as little dishonour as possible’ Oliver Stanley, President of the Board of Education, cited in Tim Bouverie, Appeasing Hitler (London: Vintage, 2019), p. 90.

Oliver Stanley, President of the Board of Education, cited in Tim Bouverie, Appeasing Hitler (London: Vintage, 2019), p. 90.

Hitler was at least partially correct: Britain did not want another war. The horrors of the Great War were still fresh in people’s minds; economies – particularly following the Wall Street CrashThe American stock market crash of 1929 that started the Great Depression and had worldwide economic and political consequences. of 1929 – were still adjusting; Britain’s place in the international arena had suffered a decline and its military was in a parlous condition, outdated, underfunded, and undermanned. Furthermore, there was a genuine fear among the public about what another war would mean for British civilians. The spectre of large-scale bombing, in which whole cities could be wiped out in one night, loomed large. It was felt better to show restraint and encourage Hitler to do likewise – the British government even sent Hitler a checklist of treaties, asking him which he intended to honour – than to provoke the utter destruction of the country. In so many ways, then, there was not the appetite nor the means to wage a large-scale, modern war.

There was one further reason for not leashing Hitler too firmly. Although Hitler was expected to expand his territory, the hope was that he would seek this LebensraumGerman for 'living space'. Territory that is believed, particularly by the Nazis, to be needed for a state to exist. in the east and in doing so provide a necessary bulwark against communismA theory of system of government and social organisation where property is owned collectively and each person contributes and receives according to their ability and needs. and Soviet Russia. Many, including the new – and never-crowned – king of England Edward VIII even welcomed the strengthening of this first line of defence provided by Nazi Germany. Nor was the king the only one: as late as 1 September 1939, the duke of Westminster, Hugh Grosvenor, was lecturing any person who would listen about Hitler and Britain being ‘best friends’, and blaming the Jews for creating a crisis. Bouverie, p. 1.

Bouverie, p. 1.

A Couple of Cassandras

There were some establishment figures, however, who correctly predicted Hitler’s course from the moment he took power. Sir Horace Rumbold, British Ambassador to Germany during the early Nazi years, was in Berlin in 1933. In April that year, just a few months after Hitler came to power, Rumbold sent a dispatch to Britain:

… the only programme … which the Government appear to possess may be described as the revival of militarism and the stamping out of pacifism. The plans of the Government are far-reaching, they will take several years to mature and they realise that it would be idle to embark on them if there were any danger of premature disturbance either abroad or at home. They may, therefore, be expected to repeat their protestations of peaceful intent from time to time and to have recourse to other measures, including propagandaBiased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view., to lull the outer world into a sense of security.

Rumbold to Simon, 26 April 1933, in E. L. Woodward and Rohan Butler (eds), Documents on British Foreign Policy, 1919-1939, 2nd Series (London: HMSO, 1956) Vol. V, pp. 47-55 (hereafter DBFP).

Winston Churchill, at that point of Boer WarThe (Second) Boer War was a conflict between the British Empire and two Boer Republics over the Empire's influence in Southern Africa, 1899-1902. (The First Boer War, fought between December 1880 and March 1881, was between the Empire and the South African Republic, over the Republic's independence - which it won.) fame and Gallipoli infamy, was another who had read the situation correctly. Hounding the government from the back benches – his political star was on the wane in the early 1930s – he was consistently hawkish, arguing for British rearmament and for a harsher line on German expansionism. In this he was aided by Foreign Office ‘spies’: people feeding Churchill information on German rearmament and British preparedness, who were concerned not just about the direction of Germany’s foreign policy, but also about the British government’s inability – or unwillingness – to do anything about it.

But by the mid- to late-thirties, government policy was decided: Germany must be appeased. Once Germany’s aims had been achieved, Britain hoped and Hitler promised, a secure peace could be found. The problem was, this approach rested upon one fundamental assumption: that Hitler was an honest and honourable man, and that he was willing to play by the same rules as everyone else. As the decade drew on, this became more and more tenuous a supposition, as treaties fell by the wayside, promises were consistently broken, and Germany’s demands and actions grew in both scope and scale. Yet there was a determination to continue along the path, particularly by Britain’s prime minister, Neville Chamberlain. It didn’t help that Chamberlain, who became prime minister in 1937, was driven by an almost messianic sense of his own destiny: his Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden (who resigned in 1938 over Britain’s foreign policy direction), complained that ‘the difficulty is that N. believes that he is a man with a mission to come to terms with the dictators’. Bouverie, pp. 158-9. This was coupled with an arrogance and vanity that not only made the prime minister unwilling to allow other views but also to revel in his perceived foreign policy ‘wins’. In August 1937, he wrote to his sister Ida congratulating himself that ‘I can look back with great satisfaction at the extraordinary relaxation of tension in Europe … I only have to raise a finger & the whole face of Europe is changed!’

Bouverie, pp. 158-9. This was coupled with an arrogance and vanity that not only made the prime minister unwilling to allow other views but also to revel in his perceived foreign policy ‘wins’. In August 1937, he wrote to his sister Ida congratulating himself that ‘I can look back with great satisfaction at the extraordinary relaxation of tension in Europe … I only have to raise a finger & the whole face of Europe is changed!’ Robert Self (ed.), The Neville Chamberlain Diary Letters: Volume IV, The Downing Street Years, 1934-1940 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), p. 265. If ever there were hubris, this would be it.

Robert Self (ed.), The Neville Chamberlain Diary Letters: Volume IV, The Downing Street Years, 1934-1940 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), p. 265. If ever there were hubris, this would be it.

Anschluss

The British policy was put to the test on 12 March 1938 when Hitler ordered the ‘reunification’ of Austria with Germany in his first major step toward creating the Greater German Reich. Ever since the publication of Mein Kampf, it had been clear that Hitler wanted unification between the two countries, arguing for it on the basis of ‘shared blood’. Despite some obvious international issues – like the fact that Austria was a sovereign nation and that other states, notably Italy in the early 1930s, had interests in protecting its borders – some considered that this was a fair request. Certain sections of the Austrian population had been pressing for closer contact with their German neighbour for years, and these calls had gradually been growing more clamorous, helped in part by the influence of heavy German propaganda and machinations behind the scenes (including links between the Nazi regime and the assassination of the Austrian Chancellor, Engelbert Dollfuss, in 1934), but also in Austria witnessing a seemingly miraculous change of fortune for their neighbour.

In an effort to regain control, and as a two-fingered salute to Hitler, the Austrian chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg announced a plebiscite on the Anschluss – or unification – for 13 March 1938. Hitler responded with an immediate threat of force. With troops amassing on the Austro-Bavarian border, Schuschnigg was presented with an ultimatumA final, uncompromising demand or set of terms, the rejection of which could lead to a severance of relations or to the use of force.: either cancel the plebiscite and resign, or Austria would face civil war and an immediate invasion. The beleaguered Austrian chancellor turned to Britain for advice. The problem was, Britain was neither able nor willing to help. As the Foreign Minister, Lord Halifax reiterated to the outgoing German ambassador, Joachim von Ribbentrop, on 11 March: ‘we had no desire to place obstacles in the way of peaceful agreement reached by peaceful means. We recognised the reality of the problems from the German point of view, connected with Austria and Czechoslovakia.' Documents on German Foreign Policy, 1918-1945 Series D, Vol. I From Neurath to Ribbentrop, September 1937-1938 (London: HMSO, 1949), p. 259 (hereafter DGFP). A peaceful takeover of power was acceptable – and, indeed, something to be worked towards. Halifax sent a telegram back to Schuschnigg, advising him there was nothing that Britain could do.

Documents on German Foreign Policy, 1918-1945 Series D, Vol. I From Neurath to Ribbentrop, September 1937-1938 (London: HMSO, 1949), p. 259 (hereafter DGFP). A peaceful takeover of power was acceptable – and, indeed, something to be worked towards. Halifax sent a telegram back to Schuschnigg, advising him there was nothing that Britain could do.

The next day German tanks rolled across the border. Instead of being met by defensive fire, they were greeted with hordes of Austrians, cheering them as if they were liberators. But it wasn’t all smiling Mädchen, handing out flowers to German soldiers against an Alpine backdrop. For some Austrians, the Anschluss was the start of an ‘orgy of sadism’. Political opponents were arrested, tortured and murdered; Jews suffered terribly, with many who weren’t killed driven to suicide. As the American war correspondent William Shirer recorded:

Day after day large numbers of Jewish men and women could be seen scrubbing Schuschnigg signs off the sidewalk and cleaning the gutters. While they worked on their hands and knees with jeering storm troopers standing over them, crowds gathered to taunt them. Hundreds of Jews, men and women, were picked off the streets and put to work in public latrines and the toilets of the barracks where the S.A. and the S.S. were quartered. Tens of thousands more were jailed. Their worldly possessions were confiscated or stolen.

William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (London: Pan Books, 1960), p. 430.

While most of the British, including illustrious figures like the Archbishop of Canterbury, congratulated Hitler on this peaceful coupA sudden, and often violent, illegal seizure of power from a government. and looked forward to a period of renewed peace and stability in central Europe, Hitler took another view of the British reaction. As Speer wrote, ‘His aims could only have been thwarted by superior counterforces, and in 1938 no such forces were visible. Quite the opposite: the successes of that year encouraging him to go on forcing the already accelerated pace.’ Speer, p. 163.

Speer, p. 163.

Peace for our time

What applied to one country would surely apply to others and the most obvious next target was the Sudetenland, the largely ethnic German area in southwestern Czechoslovakia. For several years beforehand, steps had been taken by the Nazi Party to prepare for the area, containing about three million Germans, to be subsumedIncluded or absorbed into something else. by the Reich, including the secret financing of the Sudeten German Party. Now, in early 1938, the Party’s leader, Konrad Henlein, was given instructions to up the pressure by making demands that ‘are unacceptable to the Czech Government’, including ‘for self-administration and reparation’ and later for ‘their own German regiments with German officers, and military commands to be given in German’. Effectively, he was told, ‘We must always demand so much that we can never be satisfied.’ DGFP, Series D, Vol. II, p. 198.

DGFP, Series D, Vol. II, p. 198.

By May 1938, rumours were flying that a build-up of German military on the border would lead to imminent invasion, prompting the British to issue stern warnings to Hitler while secretly hinting that ‘If there was a possibility here of settling the [Sudeten] question by peaceful political means, the British Government was prepared to enter into serious negotiations.’ In fact, the rumours were false but Hitler’s denial was still seen as a climb-down. In the same conversation, civil servantA government official - someone who works for the government. and close friend of Chamberlain, Sir Horace Wilson, went on to discuss Germany’s longer-term policies for south-eastern Europe and the Balkans, stating that ‘Great Britain [had no] intention of opposing a development of German economy in a southeasterly direction. Her only wish was that she should not be debarred from trade there.’

In fact, the rumours were false but Hitler’s denial was still seen as a climb-down. In the same conversation, civil servantA government official - someone who works for the government. and close friend of Chamberlain, Sir Horace Wilson, went on to discuss Germany’s longer-term policies for south-eastern Europe and the Balkans, stating that ‘Great Britain [had no] intention of opposing a development of German economy in a southeasterly direction. Her only wish was that she should not be debarred from trade there.’ Ibid., pp. 608-9.

Ibid., pp. 608-9.

While elements of the British government were surreptitiously discussing future German expansion with Nazi Party leaders, the planned victims were requesting help. The primary sourceis information that comes from or close to the event or person being studied. of assistance for the Czechs was expected to come from the French and Soviets, thanks to a 1935 mutual defence pact. The British were, therefore, terrified of a German military settlement to the Sudeten question, believing that a German invasion would quickly embroil the rest of the continent in war. A resolution by peaceful means was thus essential. As Chamberlain pessimistically told the British public on BBC radio:

How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is, that we should be digging trenchesLong, narrow ditches and trying on gas marks here, because of a quarrel in a faraway country between people of whom we know nothing … However much we may sympathize with a small nation confronted by a big and powerful neighbour, we cannot in all circumstances undertake to involve the whole British Empire in war, simply on her account.

Cited in Frank McDonough, The Hitler Years: Triumph, 1933-1939 (London: Head of Zeus, 2019), p. 345.

The French, having changed to a more pacifistA person who believes that war and violence are unjustifiable, or the belief that war and violence cannot be justified. government headed by Edouard Daladier, were ready to agree. So when Hitler gave a particularly rousing, violent speech against Czechoslovakia at the Nuremberg rally on 12 September 1938, and Chamberlain responded by flying to Berchtesgaden in the original example of ‘shuttle diplomacy’, the French quickly acquiesced. Following Chamberlain’s return, Daladier flew to London for a conference on the subject – during which Chamberlain fudged the details – and the two parties came to an agreement, known as the Anglo-French Plan, on the fate of the third. In effect, they would ‘give’ Hitler the areas of Czechoslovakia that contained populations with over 50 per cent ethnic Germans in return for a new guarantee to the now much-reduced country. Czechoslovakia would in turn be given an ultimatum: accept the terms, or face Germany alone.

A triumphant Chamberlain returned to Germany on 22 September clutching the agreement, only to discover that Hitler had moved the goalposts. He would no longer be happy with what he had demanded earlier that month because the situation had changed: Poland and Hungary also had claims on Czechoslovakia, so obviously it would be disingenuous to proceed without them. He also now wanted more territory for Germany, to be agreed by plebiscite at some point in the future but without any guarantees against further claims, and a list of other demands including the withdrawal of all Czech armed forces, police, and customs officials; the discharge of all ethnic Germans serving within the Czech forces or police; and the liberation of German ‘political prisoners’. Furthermore, ‘The evacuated Sudeten German territory is to be handed over without destroying or rendering unusable in any way military, commercial, or traffic establishments. These include the ground organization of the air service and all wireless stations. All commercial and transport materials, especially the rolling stock of the railway system, in the designated areas, are to be handed over undamaged. The same applies to all public utility services (gas works, power stations, etc.). Finally, no foodstuffs, goods, cattle, raw material, etc. are to be removed.’ DGFP, Series D, Vol. ii, pp. 908-10.

DGFP, Series D, Vol. ii, pp. 908-10.

Chamberlain returned to England to discuss this new plan, known as the Godesberg Memorandum, with his Cabinet. In one of a long line of calamitous errors of judgement, Chamberlain told them that Hitler ‘would not deliberately deceive a man whom he respected and with whom he had been in negotiation, and he was sure that Herr Hitler now felt some respect for him.’ Furthermore, he believed it when ‘Herr Hitler had also said that, once the present question had been settled, he had no more territorial ambitions in Europe.’ TNA CAB 23/95/42

TNA CAB 23/95/42

Munich

Despite Chamberlain’s recommendations, the Cabinet was inclined to pessimism. The French, too, indicated that the Godesberg Memorandum was a step too far. As Europe teetered on the brink of war, with Czechoslovakia beginning to mobilize, the Italian fascist dictatorA ruler with total power over a country. Benito Mussolini stepped in with a proposal: the four countries – Germany, Britain, France and Italy – should meet for a conference. No mention was made of Czechoslovakia, or her ally the Soviet UnionThe Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) or Soviet Union, was a Marxist-Leninist state covering much of eastern Europe, Russia and Asia between 1922 and 1991., attending.

The Munich Conference, held on 29-30 September, went smoothly, largely because the four nations had already pre-agreed the main points using the Godesberg Memorandum as a template. It was a fait accompli that was presented to the Czech government. With her allies having conspired with her enemies, there was little Czechoslovakia could do but concede defeat. Eleven thousand square miles were ceded to Germany and 2.8 million Germans were repatriated, but 800,000 Czechs were displaced. With its citizens Czechoslovakia also lost its military defences and much of its industry, left with an undefended rump and the promise of plebiscites that never happened. The Czech president, Edvard Beneš, resigned a week later, leaving for Britain in October, living first in Putney and then in Aylesbury. Britain eventually recognized him as the president of the Czech government in exile from November 1940. Chamberlain, meanwhile, crowed to the House of Commons: ‘I have no doubt whatever now, looking back, that my visit alone prevented an invasion, for which everything was ready.’

Britain eventually recognized him as the president of the Czech government in exile from November 1940. Chamberlain, meanwhile, crowed to the House of Commons: ‘I have no doubt whatever now, looking back, that my visit alone prevented an invasion, for which everything was ready.’  Hansard, 28 September 1938.

Hansard, 28 September 1938.

Fear of war informed Chamberlain’s opinion:

That morning he had flown up the river over London. He had imagined a German bomber flying the same course. He had asked himself what degree of protection we could afford to the thousands of homes which he had seen stretched out below him, and he had felt that we were in no position to justify waging a war to-day in order, to prevent a war hereafter.

TNA CAB 23/95/42.

But despite the pessimism of British intelligence, and the hyperbole of German propaganda, it is by no means certain that Germany would have won the fight for the Sudetenland. In fact, as high-level contacts within the German army had tried to tell a selectively deaf Chamberlain, a declaration of war by Hitler on Czechoslovakia might have led to his early downfall: plans had been hatched to seize Hitler once he had initiated the conflict and to bring him before the courts. Whether this coup would have been successful or not, it is more than likely that the German war machine would have spluttered to a grinding halt anyway. The military defences that Czechoslovakia had been forced to abandon – worse, to give to the Germans – included 1.5 million rifles, 750 aircraft, 600 tanks and 2,000 artilleryLarge guns used in warfare, or referring to the group that uses those guns. guns, as well as the Skoda armaments factory. Up against a modern army of 37 Czech divisions, Hitler would only have been able to mobilize 24 German ones – and only by leaving his western borders virtually undefended – with just four weeks’ worth of petrol, and would also have had to face the combined might not just of Czechoslovakia, but of Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. McDonough, pp. 348-9. As Speer recorded:

McDonough, pp. 348-9. As Speer recorded:

The Czech border fortifications caused general astonishment. To the surprise of experts a test bombardment showed that our weapons would not have prevailed against them. Hitler himself went to the former frontier to inspect the arrangements and returned impressed. The fortifications were amazingly massive, he said, laid out with extraordinary skill and echeloned, making prime use of the terrain. “Given a resolute defence, taking them would have been very difficult and would have cost us a great many lives. Now we have obtained them without loss of blood."

Speer, p. 9.

Diplomatically, the fact that the Soviet Union had been so thoroughly ignored – thanks at least in part to Chamberlain’s ideological stance against them that, in practical terms, was greater than Hitler’s – would also have disastrous consequences in the run-up to the actual declaration of war in September 1939. As one historian has succinctly put it, ‘In sum, Chamberlain totally misread how much the balance of power was loaded in favour of Hitler’s potential enemies in 1938 than it was in 1939.’ McDonough, pp. 348-9.

McDonough, pp. 348-9.

Pain in the Rump

Hitler felt somewhat cheated by the outcome of Munich. As Heinrich Himmler allegedly explained to his physician, ‘The Führer wants war because he believes it is important for the good of the German people. War makes men stronger and more virile.’ Joseph Kessel, The Man with Miraculous Hands (London: Elliott & Thompson, 2023), p. 42. What is more, Hitler held a personal grudge against the remains of Czechoslovakia, as well as seeing it still as a military threat, and so there was never a doubt in his mind that the rest of the country needed to be destroyed – no matter how accommodating the new Czech government was.

Joseph Kessel, The Man with Miraculous Hands (London: Elliott & Thompson, 2023), p. 42. What is more, Hitler held a personal grudge against the remains of Czechoslovakia, as well as seeing it still as a military threat, and so there was never a doubt in his mind that the rest of the country needed to be destroyed – no matter how accommodating the new Czech government was.

As with the Sudetenland, Hitler exploited internal political divisions to turn the situation to his advantage. Slovak national sentiment was manipulated, with calls for independence increasing in volume until the regional government was dismissed as a threat to national security. This, however, gave Hitler the perfect excuse to interfere – without breaking the Munich agreement – and demand not only full independence for Slovakia but also the full demobilization of the Czech army.

Under considerable pressure, Beneš’s replacement as president, Emil Hácha, travelled to Berlin on 14 March 1939 to plead with Hitler in person. Hitler, however, was preoccupied watching a romanticCharacterised by expressions of love; or an idealised way of looking at something; or someone who followed the Romantic artistic movement, that focused on individualism and emotion. comedy, so the aging, stressed, and never entirely competent Hácha was forced to wait until 1:15am the following morning to receive his audience. It did not go well. Hitler presented Hácha with a simple ultimatum: at 6am, the German army would enter Czechoslovakia. From there,

There were two possibilities. The first was that the entry of the German troops might develop into fighting. In this case resistance would be broken by brute force with all available means. The other possibility was that the entry of the German troops would take place satisfactorily, in which case it would be easy for the Führer, upon the reconstruction of Czech national life, to accord Czechoslovakia a generous way of life of her own, autonomy, and a certain measure of national liberty.

DGFP, Series D, Vol. IV, p. 267

At some point during the gruelling interview, the pressure became too much for Hácha, who either passed out or suffered a minor heart attack. But even this didn’t allow him to escape Hitler’s tirade for long: Hitler’s personal doctor, Dr Morrell, administered a ‘rejuvenating’ injection and Hácha came around enough to agree to the seeming lesser of Hitler’s two evils.

As promised, at 6 o’clock that morning German troops crossed the border. Three hours later they were in Prague, without a shot being fired.

The last straw

The annexation of the rump of Czechoslovakia came as a nasty shock to many in the British government. As the Daily Telegraph wrote in an editorial the following day, Hitler had ‘dropped the mask’ on his pretension that ‘all he sought was the correction of injustices inflicted on Germans.’ Daily Telegraph, 16 March 1939. Chamberlain, however, delivered the news to the House of Commons with a ‘remarkable state of detachment’ before suggesting that his policy of appeasement would continue:

Daily Telegraph, 16 March 1939. Chamberlain, however, delivered the news to the House of Commons with a ‘remarkable state of detachment’ before suggesting that his policy of appeasement would continue:

Let us remember that the desire of all the peoples of the world still remains concentrated on the hopes of peace and a return to the atmosphere of understanding and good will which has so often been disturbed. The aim of this Government is now, as it has always been, to promote that desire and to substitute the method of discussion for the method of force in the settlement of differences.

Hansard, 12 March 1939.

The outcry, both in the CommonsPeople who weren't members of the clergy nor the nobility, or the House of Commons. and in the papers, soon prompted Chamberlain to take a harder stance – including the exchange of mutual defence guarantees to Poland, Romania and Greece – but there remained nothing that Britain would do about the former Czechoslovakia. Although Hitler had broken the spirit of the Munich agreement, he had not broken the letter: the state had collapsed from within, and had seemingly acquiesced in its annihilation.

While Germany pressed ahead with plans for the invasion of Poland – based on claims over the return of Danzig (declared a ‘free city’ under Versailles, with Poland exercising considerable control, although being inhabited almost entirely by Germans) and freer access across the Polish Corridor (which gave Poland access to the Baltic Sea, but which cut East Prussia off from the rest of Germany) – parliament began its summer holiday and Chamberlain went fishing. As he wrote in a letter to his sister, Hilda, at the end of July, he considered that ‘Hitler now realises that he can’t grab anything else without a major war and has decided therefore to put Danzig into cold storage’. Any concern expressed by the House of Commons was nothing but a way ‘to attack & weaken the PM’.  Self, p. 435.

Self, p. 435.

Hitler was equally deceived, believing from experience that Britain and France (who had also given assurances of help to Poland) were once again just posturing. As he said in a meeting with his generals in late August, ‘Our opponents are little worms. I saw them in Munich.’ Excerpt from the diary of Wilhelm Canaris, in André Brissaud, Canaris: Legende und Wirklichkeit (Augsburg: Bechtermünz Verlag, 1996) p. 234. But the plans to invade Poland were not the only ones on which Hitler was working. Despite the ideological opposition – and the fact that they had been the declared enemies of the Nazis since the party’s inception – on 23 August 1939 the new German Foreign Minister (and former ambassador to Britain), Ribbentrop, shocked the world by signing a non-aggression pactAn agreement between countries that they will not attack each other for a specified period of time. with his Soviet counterpart, Vyacheslav Molotov. It was a brilliant diplomatic coup, removing an enemy of Germany and a potential friend of Poland and Britain in one go. If, in the unlikely event that Britain and France did declare war, Germany would no longer have to fight on two fronts. Furthermore, British and French logistical support for Poland would be made considerably more difficult with no ally in eastern Europe.

Excerpt from the diary of Wilhelm Canaris, in André Brissaud, Canaris: Legende und Wirklichkeit (Augsburg: Bechtermünz Verlag, 1996) p. 234. But the plans to invade Poland were not the only ones on which Hitler was working. Despite the ideological opposition – and the fact that they had been the declared enemies of the Nazis since the party’s inception – on 23 August 1939 the new German Foreign Minister (and former ambassador to Britain), Ribbentrop, shocked the world by signing a non-aggression pactAn agreement between countries that they will not attack each other for a specified period of time. with his Soviet counterpart, Vyacheslav Molotov. It was a brilliant diplomatic coup, removing an enemy of Germany and a potential friend of Poland and Britain in one go. If, in the unlikely event that Britain and France did declare war, Germany would no longer have to fight on two fronts. Furthermore, British and French logistical support for Poland would be made considerably more difficult with no ally in eastern Europe.

From the moment the Nazi-Soviet Pact was announced, it was clear that war would be inescapable – even the painfully unrealistic Chamberlain began to concede defeat. Yet last-minute communiques flew between London and Berlin, as well as between Washington, Rome, and Paris, hoping for a negotiated settlement. Sensibly, preparations for war continued concurrently: reservists were called up, merchant ships and fishing trawlers were requisitioned, air defence systems were put on stand-by. Even the evacuation of children from the cities was discussed – and then put on hold.

The German invasion began on 1 September 1939. Although it took a while for reports to come in, and even longer to verify them, by that afternoon the British government could be in no doubt that German forces had crossed the border and were attacking their Polish neighbours. Their first ‘note’ to Hitler was issued shortly thereafter:

[U]nless the German Government are prepared to give His Majesty's Government satisfactory assurances that the German Government has suspended all aggressive action against Poland and are prepared promptly to withdraw their forces from Polish territory, His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom will without hesitation fulfil their obligations to Poland.

TNA CAB 23/100/47

But there was hesitation. When the British ambassador was questioned on whether this was an ultimatum, he responded in the negative. And when Italy suggested the potential for further conference between Britain and Germany, Chamberlain took the proposal to his Cabinet. There, they decided that there could, perhaps, be room to negotiate – as long as German troops were removed from Polish soil. Although this dithering wasn’t quite as weak-willed as it first seemed – after all, no-one expected Hitler to agree to the terms, and the British had been begged by France to give them more time – it did not go down well in parliament. Their demand that ‘there shall be no more devices for dragging out what has been dragged out too long’ prompted a late-night emergency meeting of the Cabinet on 2 September. Hansard, 2 September 1939.

Hansard, 2 September 1939.

At last it was decided: the British ambassador would visit Ribbentrop at 9 o’clock on the morning of Sunday, 3 September and would finally issue the ultimatum. Reiterating the previous note, this new message continued:

Although this communication was made more than 24 hours ago, no reply has been received, but German attacks upon Poland have been continued and intensified. I have, accordingly, the honour to inform you that unless not later than 11 a.m., British Summer Time, to-day, September 3rd, satisfactory assurances to the above effect have been given by the German Government and have reached His Majesty's Government in London, a state of war will exist between the two countries as from that hour.

Ibid., 3 September 1939.

As Chamberlain told a packed House of Commons later that day, ‘No such undertaking was received by the time stipulated, and, consequently, this country is at war with Germany.’ He continued:

This is a sad day for all of us, and to none is it sadder than to me. Everything that I have worked for, everything that I have hoped for, everything that I have believed in during my public life, has crashed into ruins. There is only one thing left for me to do; that is, to devote what strength and powers I have to forwarding the victory of the cause for which we have to sacrifice so much. I cannot tell what part I may be allowed to play myself; I trust I may live to see the day when Hitlerism has been destroyed and a liberated Europe has been re-established.

Ibid.

Epilogue

Sadly for Chamberlain, this was one more wish he would not see fulfilled. Following a string of further failures, culminating in the inability of Britain to save Norway from occupation, the Commons had had enough. During the Norway Debate of 7-8 May 1940, Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement caught up with him. As the Labour leader Clement Attlee said:

Norway comes as the culmination of many other discontents … Norway follows Czecho-Slovakia and Poland. Everywhere the story is "Too late." The Prime Minister talked about missing buses. What about all the buses which he and his associates have missed since 1931? They missed all the peace buses but caught the war bus. The people find that these men who have been consistently wrong in their judgment of events, the same people who thought that Hitler would not attack Czecho-Slovakia, who thought that Hitler could be appeased, seem not to have realised that Hitler would attack Norway.

Ibid., 7 May 1940.

A vote of no-confidence was forced, and lost. On 10 May, the same day that Germany launched the devastating invasion of France, Holland and Belgium, Chamberlain stepped down as prime minister, to be replaced by his almost-constant critic Winston Churchill. Shortly thereafter, bowel cancer struck. Chamberlain never saw the liberation of France, let alone the day that Hitlerism was destroyed. He died on 9 November 1940, aged 71.

Things to think about

- Was Chamberlain correct to attempt to come to terms with Hitler?

- When would it have been appropriate to declare war on Germany?

- How legitimate were Hitler's complaints about the Versailles Treaty?

- How much does hindsight affect our opinion of appeasement?

- Would Churchill and other opponents of appeasement be listened to in a similar situation today?

- Was Britain morally obligated to help Czechoslovakia?

- Would the Second World War have been smaller - or not happened at all - had Britain stood up to Hitler earlier?

Things to do

- There are some fantastic primary sources for appeasement online. Look at Hansard (the record of House of Commons activity) for speeches and debates, and the National Archives for the top secret debates in Cabinet.

- The Imperial War Museum holds a considerable collection of oral histories relating to appeasement and German expansion. Many of them are searchable from here.

- Many of the press archives are also available online. The BBC has a collection of important speeches and news footage from 1938 onwards, while the website Newspapers.com has a searchable archive of regional and national newspapers going back to the 1690s (Ancestry subscription required).

- A number of museums feature different exhibits that consider the approach of the Second World War. For starters, try the Imperial War Museum, the National Army Museum, and the Churchill War Rooms.

Further reading

There is a huge number of books on appeasement, Neville Chamberlain, and the run-up to the Second World War. One of the best on appeasement is the wonderfully readable and well-researched Appeasing Hitler by Tim Bouverie. For an international perspective on the behind-the-scenes manoeuvring, and particularly on the support Hitler had amongst the upper classes, Karina Urbach's Go-Betweens for Hitler is a surprising and enlightening read.

For an overview of the build-up to war from the German side, Frank McDonough's first volume of The Hitler Years is useful for providing a rounded, general take on the regime and its policies. For those who want a taste of the primary sources without going into depth with the Documents on German Foreign Policy, try J. Noakes and G Pridham's third volume of Nazism.

Cover image: The signatories of the Munich Agreement (from left to right: Chamberlain, Daladier, Hitler, Mussolini, and the Italian Foreign Minister Count Galeazzo Ciano). © IWM NYP 68066

- Log in to post comments