Edward Shawcross: In Conversation

Edward Shawcross is a historian and teacher, who has worked and taught around the world before settling back in the UK. His first book, The Last Emperor of Mexico, was published early in 2022 and has gone on to be showered with praise by critics and audiences alike, with several publications naming it their 'Book of the Week'. In between teaching, touring, and talking about his fantastic book, Edward Shawcross set aside some time to chat about The Last Emperor of Mexico, about the importance of history, and about his future plans.

You're at Chalke Valley talking about your new book, The Last Emperor of Mexico. What’s it about?

It is an operatic story on a grand scale. The book describes the life of Ferdinand Maximilian, a Habsburg born in imperial splendour in Vienna, but rather bizarrely dying in squalor atop a Mexican hill overlooking a small provincial town. So, it is about his journey, and trying to explain how and why he ended up in that position.

And what do you think are the primary reasons for him ending up like that?

It's an extraordinary tale of hubris and arrogance. Mexico in the mid-nineteenth century is what we would anachronistically call a ‘failed state’. It actually became independent from Spain as a monarchyThe king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head., whereas most other Latin American countries became republics. That monarchy is very short lived, but the dream of monarchists never dies. Increasingly, as Mexico becomes more and more of a failed state going through several revolts and civil wars, there's the notion that it could return to the original idea of an independent monarchy, which would restore stability. Mexico is also in close proximity to the United States of America, and in 1846 the US invades Mexico and seizes half of its national territory. This trauma, and humiliation, compounds the instability of Mexican politics. So, the monarchists invite Ferdinand Maximilian to take the throne in 1861. Of course, if you're looking for a monarchA king, queen, or emperor in the mid-nineteenth century, the name Habsburg is above all others. There's one small problem: they have no throne to offer because these monarchists are on the defeated side in the Mexican civil war, which was won by a group of liberals led by Benito Juárez (a great hero in Mexican history), who was democratically and constitutionally confirmed as president. What the monarchists are trying to do is revive the civil war that they've lost. There's one additional ingredient they need to do that, which is the emperor of the French, Napoleon III. They go to him with a plan, which is deceptively simple: they just need a few thousand French troops who will turn up on the shores of Mexico, pronounce Ferdinand Maximilian emperor and the Mexican people will rally to his cause. What could go wrong?!

Maximilian seems like such a likeable character: very charismatic, but ultimately pretty inept.

He is an incredibly contradictory character and at the same time incredibly likeable. There are elements in which he is very disagreeable, especially to a twenty-first-century audience: he's a Habsburg; he's obsessed with his dynastyA line of hereditary rulers of a country, business, etc. and his destiny, which is why he accepts the role as emperor of Mexico – even though it becomes increasingly apparent that it's a difficult job and there are many people in Mexico who not only dislike him, but will fight violently to the death to prevent his rule ever taking root. But there's a side to him that's liberal and, for the time, exceptionally progressive. He sees himself as a constitutional and democratic monarch, in opposition to his elder brother, Franz Josef, the autocratic ruler of the Austrian Empire. He's generous and kind; he's charismatic. This really comes across from the sources – from his speeches, from his letters to his wife, Princess Charlotte (Empress Carlotta of Mexico). There's a real humanity, and he gets caught up in events that are far beyond his ability to control. There are moments where he's very inept: he has a penchant for butterfly hunting during important meetings, which is not a leadership quality I think anyone would particularly want; he's a dreamer, and his dreams tend to be rather beautiful, like uniting the people of Mexico behind his rule; and he's very sympathetic to the indigenousNative to a particular place. peoples of Mexico. But a lot of his dreams are impractical. He's not the person needed to rescue Mexico from the abyss, but you would need someone of extraordinary capability in that situation.

Could he have succeeded, without the character flaws?

There's a real contradiction in Maximilian and what's called the Second Mexican Empire, the regime he ends up heading, which is that the people who want it most desperately – the people, in fact, who invited him to take the throne – are reactionary Catholic conservatives. What they actually want is his brother. Instead, they get a moderate liberal who believes in the separation between church and state. This is the key issue the conservatives are fighting for: they want to restore the Catholic Church to its absolute position of unquestioned power, which, of course, had been challenged by many liberals in Mexican society, and by Benito Juárez himself. When Maximilian arrives in Mexico, he is expected by his followers to overturn all of these reforms that have been cutting away at the power of the Catholic Church. He doesn't: he confirms them. The counterfactual that Mexican conservatives at the time said is that Maximilian should have gone in as a reactionary and backed the conservatives. They argued that there’s a huge silent majority of Catholic conservatives in Mexico and actually the liberals, although they may win elections, are just a radicalA person who advocates thorough or complete political or social reform, or a description of that change. minority that oppresses the silent majority.

Would he have succeeded had he done that? I'd say no, he wouldn't. I think the conservatives are wrong: they're going to back him anyway and, although there's a huge amount of Catholic support for Maximilian in Mexico, the conservatives already had that when they lost the civil war. What Maximilian's doing is very pragmatic: by backing these liberal reforms he's trying to win over supporters to his regime and extend his appeal beyond the conservative power base that has failed to govern Mexico and just lost a civil war.

If Maximilian’s rule was going to work, a number of things would have to go right. The first is that when Maximilian is initially offered the throne, it's at the end of 1861; when the French forces turn up in league with the conservative allies, it's the beginning of 1862. But instead of people flocking to the flag of a foreign invader – the French tricolour – they flocked to the flag of the Mexican tricolour behind Benito Juárez. There's a famous moment in Mexican history where the French army deploys before the second city of Mexico, Puebla, and the French commander-in-chief, incredibly confident, expects to defeat the Mexican army. This is the French army that defeated the Russians in the Crimea, the Austrians in 1859, and, of course, is headed by a Bonaparte – although he’s not personally there in Mexico, it's his army, it's a Bonapartist army. The opposite is what happens: they're defeated outside the walls of Puebla, on 5 May. This battle goes down in Mexican history as Cinco de Mayo. The French don't take 'no' for an answer – that's certainly not Bonapartist behaviour – so Napoleon III sends reinforcements. But so cautious are the French now not to suffer another humiliation that the advance is gradual. It's very slow, very methodical, and very violent, further turning the population of Mexico against the regime they're about to install. So Maximilian does not march into Mexico triumphantly until 1864, over two-and-a-half years after the first offer came in. By that time, the American Civil War is nearly at an end, but the war is the reason why Washington hadn’t intervened and prevented France from deploying troops in the first place. The Monroe DoctrineThe set of beliefs upheld by a religion or political party., which is against European states interfering in American politics, is essentially a cornerstone of US foreign policy, and the last thing they want is Catholics and monarchs and Habsburgs turning up on their doorstep. So, the geopolitical space to carve out this empire is vanishingly small by 1864. Had the French gone in, had Puebla fallen, and had the French taken the capital in 1862 and Maximilian set up his regime then, you've got three years before US pressure makes it extremely difficult for Maximilian. The only way it works is if it happens quickly in 1862 and, even then, it’s still tough.

It's such an interesting story, old versus new, and different hemispheres colliding. Yet it seems that this whole episode has been overlooked, certainly by the West. Why do you think this is the case?

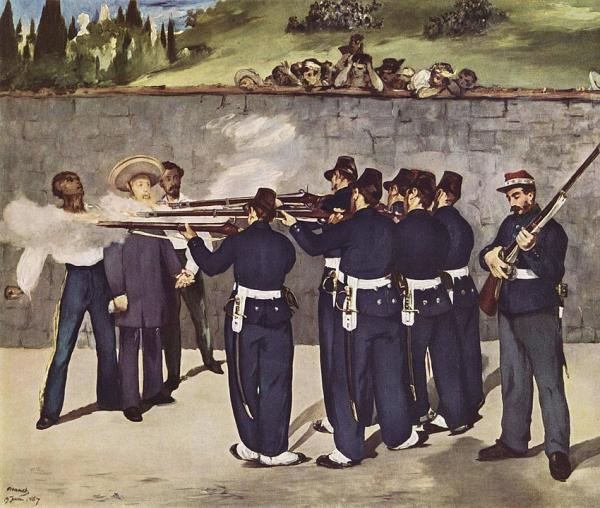

The reason it's almost forgotten in Europe and the United States is because it's happening at the same time as such enormous events. The tectonic plates in Europe are shifting: you have the Franco-Prussian War, the fall of Napoleon III, and so it doesn't have much lasting impact. In the United States, of course, you've got the Civil War and that's the big story. So apart from in Mexico, it doesn't really serve anyone's interest to tell it. It's not the dominant narrativeA story; in the writing of history it usually describes an approach that favours story over analysis. of US-Mexican relations, which is about invasion, economic exploitation, and immigration. Actually, it's a shame in many ways because it's a brief high-point in US-Mexican relations: Abraham Lincoln and, after his death, the much-maligned Andrew Johnson (the first ever US president to be impeached) do back the Mexican Republic against French imperialists and Maximilian. So, it becomes buried and almost romanticized. If it's remembered at all, it's probably remembered for the famous Manet painting, The Execution of Emperor Maximilian, and the stoicismAn ancient Greek school of philosophy that taught that virtue, the highest good, is based on knowledge, and that the wise live in harmony with the divine reason, which governs nature. As such, they thought that the wise should be indifferent to changes in fortune, and to pleasure and pain. of Maximilian's death in the face of a firing squad.

Do you think there is a need to study more world history, and to see the parallels between then and now?

Definitely I do. The Last Emperor of Mexico is a wonderful collision of different histories and cultures, first and foremost of Mexico, but then, of course, of France, Austria and the Habsburgs, the United States, Britain's involved – of course it is, it's the mid-nineteenth century! To give Napoleon III his due in what is an outrageously egregious example of imperialism, he's ahead of his time in the way that he goes about doing it, which is colonialism on the cheap. But this is incredibly reminiscent of later Western interventions – Vietnam would be the obvious one and, more recently, Iraq and Afghanistan. The term for Napoleon III’s actions that we'd use today is 'nation building', where you’re trying to implant a regime that has some local support, but there's fierce opposition as well. Despite the enormous disparity in military and economic power, it is still incredibly difficult to win ‘hearts and minds’. Maximilian's intentions were good: he's the nicest man you can have rule an evil imperialist regime, but that’s still how it’s seen by most people in Mexico. It doesn't matter how charismatic Maximilian is, outside of the imperial court and on the ground what you remember is the French soldiers bayoneting opponents and burning Mexican villages.

You worked around the world before you did your doctorate; was that always your intention?

It was incredibly unplanned and chaotic. I was one of those very geeky people who loved history from an outrageously early age, and my favourite thing was to do history projects and read about history. I loved studying at university, but when I finished my undergraduate degree, I didn't want to go straight into doing a Masters. I wanted to try a few different things and to travel, and I ended up working in France and then South Korea. When I came back to London, I found that the brutal world of the office is not what it's cracked up to be, so my partner and I moved to Colombia and I taught English as a foreign language there, which really sparked my interest in Latin American history. So it wasn't planned; it was a serendipitous wander through different things.

One thing that I did discover about myself is that I absolutely love teaching, but I did want to pursue history further. So I did the Masters and PhD, which made me about five or six years older than anyone else who was doing it, but that meant I really appreciated it and spent a lot more time studying than I did the first time around, making use of all the brilliant resources and asking those annoying questions that weren't obvious to me when I was a teenager. If I could, I think I'd carry on studying forever! I'm always really annoyed as a teacher that I'm not on the other side: I want to be where the students are. Sitting down and listening to an expert tell me information is a dream for me.

Has the way history is taught changed and do you think it needs to change further?

In essence, history is endlessly fascinating and it is possible to bring that out however it's examined or studied. The thing about history is that it's quite a wonderfully archaicVery old or old-fashioned. way of studying anything anyway. Let's take A-level: you'll do coursework, but you're going to end up doing probably three exams of maybe an hour-and-a-half, or two-and-a-quarter-hours each. You've got to write 45-minute essays as though it were some nineteenth-century civil service exam. I'm not saying you should change that, but there's something that's slightly timeless about it. You might get a question that asks, 'The main reason for the partition of India in 1947 was British policy; how far do you agree?' You could have got that question at any time in the last fifty years. Also, I remember being in exams where you finish the second essay and your hand cramps and you think, 'Oh, I'm not sure I can write the next one!', and that's got to change: it's going to go digital. It's not my preferred phrase, but if you're preparing people for ‘gainful employment’, at no point in their life is anyone going to say, 'Right, you've got two hours. I want a handwritten answer to the reasons for the partition of India’, or equivalent. It does seem there is a disjuncture between what the modern world is and what the study of humanities is. But the thing is, if you want to become the greatest and best-paid commercial lawyer in the universe, then doing a history degree followed by a law conversion course is quite a good route. You can still do history at university just because you love it, and you can then move into all kinds of different and exciting careers which have got nothing to do with history whatsoever. It teaches people how to assess information, and analyse and evaluate. Being able to process huge amounts of complex information and put it into a form that people can understand – like writing a report – is hugely important. History is a much more interesting version of doing that.

One thing I would say is that they should teach some Latin American history, because it’s pretty much the only continent that you can't study (except tangentially) in the A-level or GCSE syllabus. There's often a course on the Golden Age of Spain and you could look at conquest and colonization, but obviously the focus is Spain. Another thing that I would change is that at GCSE, there's not much time to teach the content. I would like to go off into interesting historical ditches and maybe take a bit of time to look at, say, the culture of Soviet Russia in more depth. Now, it's just so fast-paced. You have to learn a lot in not a huge amount of teaching time and that can make it quite stressful for students and can potentially put some people off.

For the next project you're taking time off from teaching?

That's right, to focus on the next book which is going to be on the 'villain', if you will, of The Last Emperor of Mexico, which is Napoleon III, the French emperor. So, I'm having to learn to 'undislike' him, to try to be more sympathetic towards him.

If you were to have a safety bubble, where in history would you go?

This is easy for me. It's not in the book because space precluded serious discussion of it, but when Maximilian is under siegeA military operation in which enemy forces surround a town or building, cutting off essential supplies, with the aim of compelling those inside to surrender., he's led his army out into this small, provincial Mexican town as a last-gasp hope to win a stunning victory over the forces of Benito Juárez. And he is betrayed by one of his officers, a guy called Miguel López. However, there is some debate as to whether it is actually a betrayal or whether he asked López to go into the enemy’s camp to organize some kind of negotiated settlement. My personal view is that he is betrayed – otherwise it would have been completely out of character – but some people argue that he pretended to be so as a way to avoid a final breakout, which would have ended in catastrophe. As it's the middle of a siege, there's no documentary evidence, but a conversation did happen on the evening of 14 May 1867 between Maximilian and the man who betrays him. So I would like to have gone into that room, and I would like to have been invisible, and I would like to have listened to what they said.

If you could invite people from any time in history to a dinner party, who would you have?

Well, I've got to have Maximilian there and I've got to have Napoleon III. This is going to make an incredibly awkward dinner party because, of course, Maximilian ends up hating Napoleon III: Napoleon withdraws French support and is the key reason why Maximilian ends up being executed. To have them there, I think, would be fireworks! I’d have Maximilian's wife, Princess Charlotte, as well, because that would just ramp up the level of fireworks, but before she loses all reason and her mind completely unravels. Those three would really make for an electric evening, if not an enjoyable one, and they would be interesting to speak to. Napoleon III was obsessed with Julius Caesar, so let's get him there, and Napoleon III's wife, Eugenie. That would really ramp it up: it would be quite a dangerous dinner party! The beauty is that it's a party that would have happened, minus Julius Caesar, before Maximilian went to Mexico. But this one would be afterwards, and perhaps they'd be able to work it out: a sort of a couples' therapy!

- Log in to post comments