Ten Facts You Might Not Know about Mary Shelley

Mary Shelley is best known as the wife of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, and as the author of the classic novel Frankenstein. But these two facts, interesting as they are, belie the depth of character and experience of this clever, unconventional, and remarkable woman.

Definitely not love at first sight

Mary Shelley was the second daughter of the famous women’s rights campaigner Mary Wollstonecraft. Wollstonecraft and Mary’s father, William Godwin, met at a dinner in honour of Thomas Paine – author and American revolutionary – but didn’t immediately hit it off: they monopolized the conversation that evening, arguing so much about religion that Paine could barely get a word in edgeways. They only got together five years later, when Wollstonecraft unconventionally called on Godwin to lend him a book.

An unconventional childhood

Mary Shelley’s father, William Godwin, married twice, despite writing against marriage in works such as Political Justice. Both of his wives were equally unconventional and, of the five children who were brought up in the Godwin household, none had both parents in common. However, Godwin wasn’t quite so open-minded when it came to his own daughter, whom he cut off until she married her lover, Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Mary eloped with her future husband when she was just sixteen

Early in 1814, while standing by her mother’s grave, the sixteen-year-old Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin declared her love for the married poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. On 28 July 1814 they eloped to the continent with Mary’s half-sister, although they soon returned pregnant and penniless. Despite the couple – and Mary’s sister – living together in a number of London lodgings for the remainder of the year, the relationship was rather intermittent as Percy was so frequently hiding from bailiffs.

Byron and Frankenstein

Mary’s step-sister, Claire Clairmont, had a brief fling with the ‘mad, bad and dangerous to know’ Lord Byron. It was because of the now-pregnant Claire, who wanted to make the liaison more permanent, that she, Mary and Percy travelled to Geneva, rather than Italy, in the summer of 1816. It was the be a fateful trip, for on a dark and stormy summer’s evening at Byron’s residence, the guests were challenged to a ghost-story competition. The unseasonable weather was caused by the eruption in Indonesia of Mount Tambora, which led to the Year Without a Summer. The result was not just Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, but also John Polidori’s The Vampyre, which went on to inspire Bram Stoker. It also started the important friendship between Percy Shelley and Byron. Sadly for Claire – and her daughter, Allegra – the summer didn’t inspire any long-lasting affection for her in Byron.

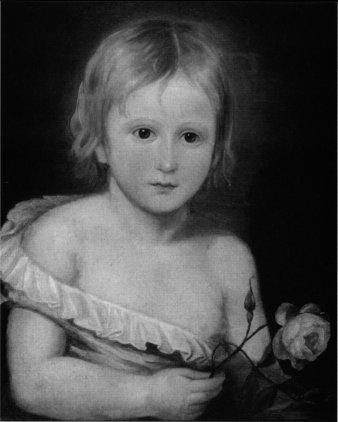

The unseasonable weather was caused by the eruption in Indonesia of Mount Tambora, which led to the Year Without a Summer. The result was not just Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, but also John Polidori’s The Vampyre, which went on to inspire Bram Stoker. It also started the important friendship between Percy Shelley and Byron. Sadly for Claire – and her daughter, Allegra – the summer didn’t inspire any long-lasting affection for her in Byron. Byron later seized Allegra from her mother and placed her in a convent, where she died aged five.

Byron later seized Allegra from her mother and placed her in a convent, where she died aged five.

Frankenstein was considered a romance

The novel for which Mary Shelley is most famous is Frankenstein, the story often considered to have started the science fiction genre. In addition to considering the impact of science and technology and the major issues of life and death, it also highlights the glaring social and economic problems of Regency Britain, making a strong case for the reform of politics and education. Originally published anonymously, critics believed it to be written by a man and so addressed the political and reformistSupporting the European Reformation of religion, where Protestants split from Catholic beliefs and practices, or supporting reform in a more general way. ideas it contained. However, when the author was discovered to be female, they started ignoring its important messages and instead considered it a romance. Those few who chose to notice the underlying themes were often disparaging, at worst stating the book should be ignored for being unfeminine, at best saying the author had a masculine mind. For context, the other famous Regency novel by a woman, Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, was published just five years before.

For context, the other famous Regency novel by a woman, Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, was published just five years before.

Two suicides…

The year 1816 was marred by suicides. On 8 October 1816, Fanny Imlay, Mary’s half-sister, travelled by coach to Swansea, where she wrote a final note:

I have long determined that the best thing I could do was to put an end to the existence of a being whose birth was unfortunate, and whose life has only been a series of pain to those persons who have hurt their health in endeavouring to promote her welfare. Perhaps to hear of my death will give you pain, but you will soon have the blessing of forgetting that such a creature ever existed …

Cited in Michelle Faubert, ‘Godwin, Frances’, at ODNB https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/103421

Having felt abandoned by her sisters as they gallivanted around Europe – and having been left to deal with the resultant scandalAn event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action. and the family’s severe financial difficulties – and been refused the once-promised job as a teacher, on 10 October Fanny took an overdose of laudanum. To avoid the scandal associated with suicide, none of the family claimed the body; some family members were still ignorant of her death a year later.

The second death was that of Harriet Shelley, Percy’s abandoned wife. Theirs had been a whirlwind romance: eloping and marrying in Scotland as teenagers before family friction, finances, and simply growing apart (on Percy’s side, at least) had encouraged Percy to look elsewhere, deserting his pregnant wife and child in the process. Although he allowed a small stipend for his wife every month once he’d come into a limited inheritance, Percy’s behaviour to Harriet became increasingly cold and cruel. At some point, she gave up on him. Having fallen pregnant – either through a new relationship or, as Shelley later claimed, through prostitution – she moved from her family lodgings. Feeling she had ‘not one ray of hope to rest on for the future’, she walked into the Serpentine in London and drowned herself.  Cited in Anna Mercer, ‘10th December and the tragic death of Harriet Shelley’, at BARS Blog http://www.bars.ac.uk/blog/?p=1514 (accessed 16/2/21) Her body was pulled from the lake a month later.

Cited in Anna Mercer, ‘10th December and the tragic death of Harriet Shelley’, at BARS Blog http://www.bars.ac.uk/blog/?p=1514 (accessed 16/2/21) Her body was pulled from the lake a month later.

…And a series of unfortunate deaths

Mary Shelley’s life was full of the untimely deaths of loved ones. Mary’s mother died just eleven days after the birth of her daughter, after the manual extraction of the placenta left her haemorrhaging and fighting infection. The Shelleys’ first child, a daughter, died after twelve days; in 1818 their remaining living daughter, Clara, contracted and died of dysentery in Venice; and in 1819, their son William died after catching malaria in Rome. On 16 June 1822 Mary suffered a further miscarriage and herself was only saved by her husband, who made her sit in an ice-cold bath to stop the resultant bleeding. Perhaps most devastating of all, about a month later, Percy Shelley and a friend were sailing from a meeting when a sudden storm upset their boat. Both were drowned, with Shelley’s body washing up on 18 June 1822. He was cremated a month later, during which – allegedly – his heart was snatched from the flames. His ashes were buried in the protestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. cemetery in Rome, the same cemetery that contained his son William and fellow poet John Keats.

Mary Shelley’s father-in-law couldn’t stand her

Percy’s father, Sir Timothy Shelley, deeply disapproved of Mary. Consistently refusing to meet her, he also set harsh restrictions on her life. After the death of Percy, he provided some financial assistance to the couple’s remaining son, Percy Florence Shelley. However, it came with a lot of provisos, including the raising of the child in England, when Mary would have preferred to remain on the continent. He also prohibited Mary from publishing any of her husband’s works or bringing any public attention on the name of Shelley, which should have effectively prevented her from pursuing her writing dreams: if she disobeyed his wishes, he withheld the allowance. However, this didn’t stop her from finding loopholes and ways around his rules. A conventional and increasingly conservative man, Sir Timothy liked very little about his son: he had also disapproved of Shelley’s first marriage to Harriet, leading him to cut off Percy’s allowance as well as lines of communication with him.

A conventional and increasingly conservative man, Sir Timothy liked very little about his son: he had also disapproved of Shelley’s first marriage to Harriet, leading him to cut off Percy’s allowance as well as lines of communication with him.

Transgender escapes

In the 1820s, Mary became friends with the Mary Diana Dods, the illegitimateIn terms of children, those born out of wedlock (to unmarried parents). daughter of a Scottish nobleman. Unable to support herself on her small income, Dods turned to writing under the pseudonym David Lyndsay. This adoption of a male name prefigured a much greater change, as she started dressing as a man and being addressed by the name Walter Sholto Douglas. It was under this name that Mary Shelley acquired him and his partner, the beautiful – but unmarried – mother Isabella Robinson, false passports. The couple crossed to the continent where they lived as a married couple. Douglas hoped to join the diplomatic service in Paris, but seems to have died in a debtors’ prison at some point between November 1829 and November 1830. Isabella later married the Reverend Mr. Falconer.

Not just Frankenstein

Mary Shelley’s most famous work is undoubtedly Frankenstein. But the power and imagination of this novel, and its enduring legacy in popular culture, has led to the neglect of much of her other writing. As well as editing her husband’s work, which helped his posthumous reputation as a prominent and important poet, she authored several other works, including short stories, historical and science fiction, and travel-writing. One of her works, Matilda, about a father’s inappropriate love for his daughter, was initially not published because it was considered ‘disgusting and detestable’. Mary Shelley, Matilda, ed. by Janet Todd (London: Penguin, 1992), p. xvii. Thereafter, Mary considered it unlucky; it was eventually published in 1959.

Mary Shelley, Matilda, ed. by Janet Todd (London: Penguin, 1992), p. xvii. Thereafter, Mary considered it unlucky; it was eventually published in 1959.

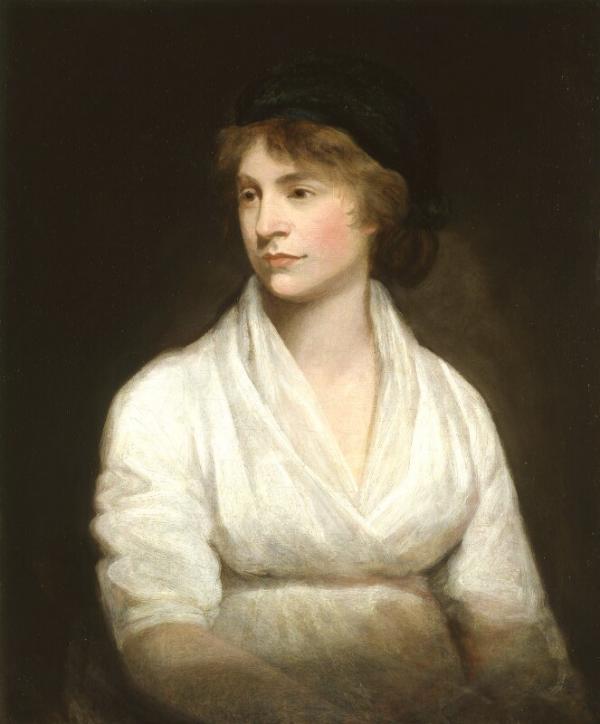

Title image: Mary Shelley by Richard Rothwell (1840). Held by the National Portrait Gallery.

- Log in to post comments