Jane Tar: Women and the Royal Navy in the Age of Sail

Key facts about women in the navy

- The presence of women onboard Royal Navy ships has been ignored until recently.

- In fact, there were a great number of women, both prostitutes and seamen's wives.

- In the heat of battle, women worked as hard as the men.

- However, they never received the credit they deserved for their actions.

There can be few historical milieus as thrilling and iconic as the lives of men at sea in the glorious Age of Sail. Images stay long in the mind, of salty sea dogs swabbing decks and deckhands in the rigging, riding out the lashings of great oceanic tempests. Here is Admiral Nelson gazing across the maelstrom of combat at Trafalgar, awaiting his apotheosis. Over there are Sir Francis Drake circumnavigating the globe in the Golden Hind and Captain James Cook braving the vast unknown of the Pacific Ocean. In literature too we find no end of delights, from Jack Aubrey on the far side of the world to Horatio Hornblower riding the waves in search of the French. And of course, there is the ever-present, sturdy Jack Tar – the nickname given to all lower deck seamen.

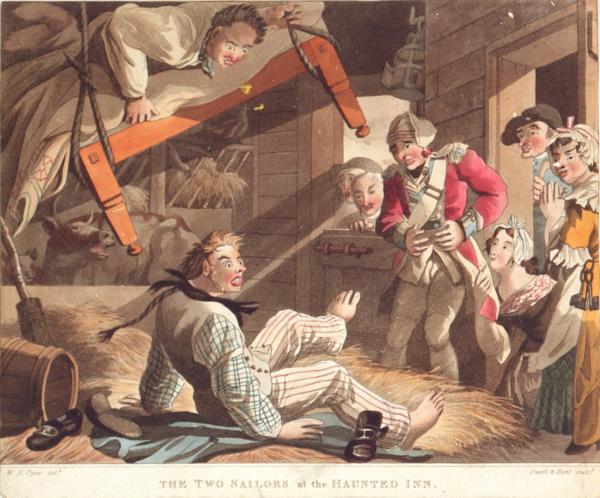

Yet there is always something in these images that is notable for its absence – the presence of women. One could be forgiven for thinking that the wooden worlds of ships in the Age of Sail were wholly male environments, with the only interaction between the sexes taking place during bawdy bouts of revelry when ships hit port. Many have heard of the sailor's superstition that a woman onboard would bring nothing but bad luck, a genuine belief which could lead to some very extreme actions. As a particularly horrific example, when Sir John Arundel sailed for Brittany in 1379, he had around 60 women on board his ships, some prostitutes and some victims of kidnappings carried out by crew members. When Arundel's fleet found itself in a huge storm, the men decided the tempest was the result of bad luck caused by the women, so they promptly threw all 60 overboard into the sea. Unsurprisingly, this rather unscientific approach to seafaring did not work and 25 of the ships were smashed to pieces off the coast of Ireland, drowning most of the men, including Arundel himself.

Because of all these stories and distorted histories, it is easy to miss the truth: ships were absolutely full of women, both in port and on the open sea.

The most obvious reason for the apparent absence of female sailors is simply that their presence was discouraged and, therefore, largely undocumented. Women onboard Royal Navy ships were never entered in the ships' muster books, unless they were among the few directly and officially permitted passage by the Admiralty – captains' wives and children would be one example. Therefore, when reading journals and accounts of voyages by those in authority, it must be remembered that the presence of women was deliberately left out. Many captains doubtless disapproved to some degree with carrying female passengers and pseudo-crew members, but even those who did not would have been obliged to leave them out of any official record. However, women were there, in far greater numbers and for a much longer period than many realise. This article is going to look at the backgrounds, the lives and the experiences of 'Jane' Tars – the women of the waves.

The underbelly in the lower decks

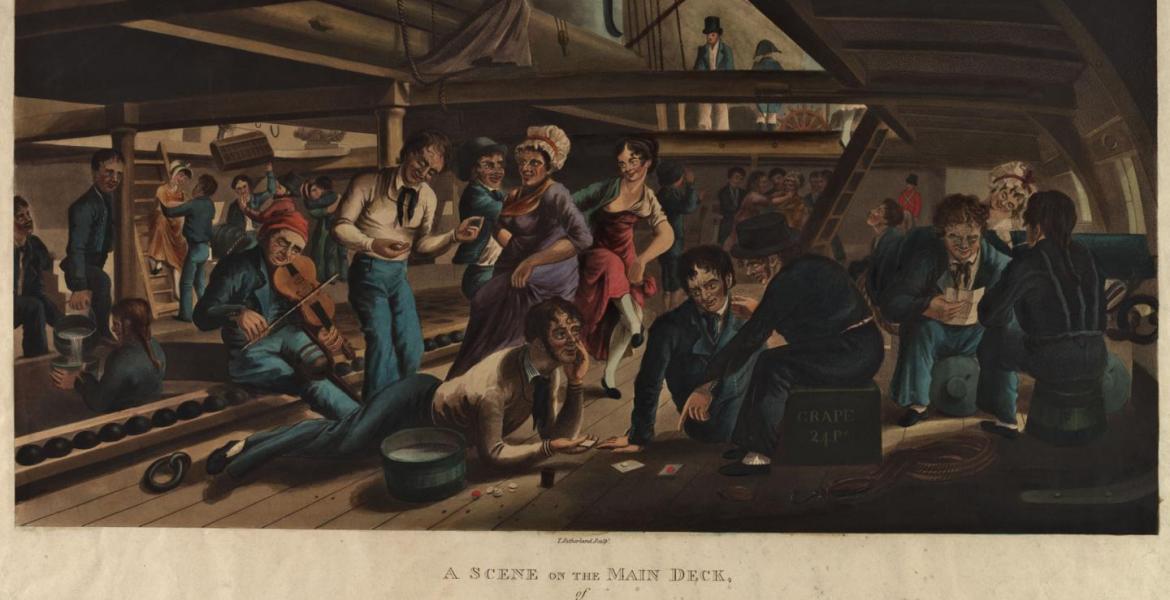

It should come as no surprise that a large proportion of the women to be found aboard ships in this period came as prostitutes. The image of the drunken cavorting sailor on shore, moving from tavern to brothel and back again is a familiar one. Yet in fact, when it came to Royal Navy vessels, most business was transacted on the sailors' ships themselves. The reason for this was quite simple. A great many sailors did not join the Royal Navy of their own volition. They were forced into service by press gangs in towns around the country and were frequently resentful as a result. When a ship hit port, its captain would be well aware that if he were to allow sailors to have shore leave, many of them would simply run off. Yet not allowing recreation of any kind would be tempting mutinyRebellion against authority, particularly of military personnel or sailors against their commanding officers.Rebellion against authority, particularly of military personnel or sailors against their commanding officers. . Therefore, instead of allowing the men to go to the women, those in authority would turn a blind eye to the women coming to the men. A secondary reason was the concern that without women, men would be encouraged to turn to homosexual liaisons instead, although N.A.M. Rodger has suggested that homosexuality was not actually as prevalent as has been thought. N.A.M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649-1815 (London: Penguin, 2004), p.407.While some officers may have been concerned about the chance of such activity increasing without the presence of women to allow an outlet for sexual frustrations, some priggish campaigners actually argued that allowing prostitutes aboard made the problem of homosexuality worse, for 'a familiarity with gross pollution has prepared the mind for further grossnesses'.

N.A.M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649-1815 (London: Penguin, 2004), p.407.While some officers may have been concerned about the chance of such activity increasing without the presence of women to allow an outlet for sexual frustrations, some priggish campaigners actually argued that allowing prostitutes aboard made the problem of homosexuality worse, for 'a familiarity with gross pollution has prepared the mind for further grossnesses'. Cited in Suzanne J. Stark, Female Tars: Women Aboard Ship in the Age of Sail (London: Constable and Company, 1996), p.42.

Cited in Suzanne J. Stark, Female Tars: Women Aboard Ship in the Age of Sail (London: Constable and Company, 1996), p.42.

In ports around the world, young prostitutes would be rowed out to docked ships in 'bumboats' by men who would sometimes receive three shillings for each woman accepted onto the ships. Sometimes these transactions became colossal events, with literally hundreds of women being taken onboard each ship, cases being recorded of more than 400 at one time.

It was less common, although not unheard of, for prostitutes to remain on ships after they left port. The situation and plight of these women must have been terrible, with far more prolonged exposure to the already revolting conditions experienced by shore-based women. The area below decks on a navy ship was deeply unpleasant. Hundreds of men sleeping on rows of hammocks with the smallest amount of space between them – 14 to 16 inches of space allowed for each hammock. There was little ventilation at all and the whole place smelled rank, a combination of poorly washed clothes, old food, human waste and sweat. Conducting their business in such an environment, women faced an experience quite difficult for us to imagine today. Beyond that there was the ever-present reality of sexually transmitted diseases for which there was little treatment available.

By the late eighteenth century, reformers and philanthropic enterprises on land had begun to try and tackle what they saw as a moral illness, starting institutions that aimed to bring prostitutes in from the world of sin and help them to find redemption – including the marvellously named 'Friendly Female Society for the Relief of Poor, Infirm, Aged Widows and Single Women of Good Character Who Have Seen Better Days'. During the nineteenth century, conditions on navy ships improved and the 'press' was abandoned, meaning that sailors were allowed shore leave, and the tradition of prostitution on ships faded away.

Tired of waiting

Perhaps even more interesting is the experience of wives who chose to join their husbands onboard ships and travel the world together. The image of the dutiful seaman's wife, lighting a candle in the window and waiting on shore for her loved one to return is as pervasive a cliché as that of the heroic captain on the top deck, taking on the enemy with relish and rounding the Horn without fear. Yet in truth, many women abandoned the loneliness and hardship of the coastal towns of Britain for a life in the lower decks. It is easy to understand why.

Far from merely waiting patiently, the lot of a navy wife involved a terrible amount of struggle. Wages from their spouses arrived extremely late, sometimes taking years to arrive at all. They were also fairly low when they actually did arrive, having remained unchanged for around 150 years until the Spithead MutinyRebellion against authority, particularly of military personnel or sailors against their commanding officers. in 1797. This drove a great number of wives into dire situations, finding themselves sent to workhouses, forcibly returned to their places of origin or even obliged to turn to prostitution to make ends meet. If a husband had been pressed into service, there were frequently times when he would simply disappear and not return for years – if at all. Far better for many women to brave the grim life on the cramped lower decks than to wait in such a state.

Although officially spouses were generally not permitted on ships, warrant officers and petty officers such as the boatswain, gunner, carpenter and others would often live alongside their wives. The situation was made extra difficult as no provision was made for their wives as they were not included in the muster books. Wives were allocated no rations and so had to share their husbands'. They had to share hammocks, which – as mentioned – already had a tiny allocation of space, even though warrant officers were afforded a little more room and a canvas to provide some privacy. These facts led to a hard life for both husband and wife, and yet they still considered it the lesser of two evils.

For better, for worse

In the case of the army, which had a long tradition of soldiers' wives being present, women who were with an army of foot soldiers would rarely have found themselves in the firing line. They would have remained in the rear, at camp. While a camp could at times find itself overrun, this was not something which occurred very often. On the other hand, a naval vessel, regardless of its relative size, was a small world, and there was no escape for any within when combat began. Combat of any kind is, and has always been, terrifying, but in a ship, the possibilities for escape from harm were far lower than on an open field of battle. Naval combat in ships during the Age of Sail was horrific.

Most women on ships when battle took place would have done much the same job as the young boys. They would have become 'powder monkeys'. Their job would have been to repeatedly make their way to the belly of the ship where the gunpowder was stored, collect some and make their way back to the gun to which they had been assigned, often that of their husband. This job did not cease, as gunpowder was not stored in bulk near the cannons – a single stray spark or well-placed shot being likely to blow the side off a ship.

It is likely that no cinematic or televisual rendering of a sea battle has ever truly recreated the ceaseless carnage of ship-on-ship combat, let alone the chaos of a full fleet action. Before the opening salvos were fired from the guns, sand was used to coat the floor to allow for a modicum of grip on what rapidly became a river of blood and strewn body parts. A single barrage would tear holes in the wooden walls of the ships, sending cannon balls across decks at speeds that could – and would – decapitate, dismember and disembowel. Just one tragic example is of one Mrs Phelan, who, caught in combat aboard the Swallow in 1812 and, cradling her dying husband Joseph in her arms, had her head taken off by a cannon ball. The two of them left behind a three-week-old son, TommyA British private soldier.A British private soldier.. Stark, p.77; Roy and Lesley Adkins, Jack Tar (London: Little, Brown, 2008), p.178.

Stark, p.77; Roy and Lesley Adkins, Jack Tar (London: Little, Brown, 2008), p.178.

The greatest fear of all was the prospect of a full broadside through the stern, which would send the balls flying the full length of a deck, potentially killing scores of people in moments and knocking loose cannons, which would slide across the decks and prove as deadly as the shots themselves. Of course, absolutely nobody was safe, the women included, as evidenced by the fate of Mrs Phelan. Many Tars, Jack or Jane, would be reduced to emotional wrecks, but the majority fought on, focusing on the actions required. These battles are usually depicted in media as brief, brutal affairs. In reality they could last for hours, with little let up in the destruction.

Further below deck, in the surgeons' rooms, things were nightmarish. Women would often assist here too, mainly clearing blood from the floor while the medical professional went about his business. This business frequently involved amputations of shattered limbs, not merely a few per battle, but a process which went on throughout. Most surgeons could complete an amputation in less than two minutes, sometimes much more quickly. Until the middle of the nineteenth century, these were done entirely without anaesthetic. The screams, the blood and the horror never stopped, all the while punctuated by vibrations through the ships as more and more cannons were fired. Cases have been recorded of pregnant women enduring the unfortunate experience of going into labour and giving birth in the middle of battle, the stress and vibrations starting the process, including one well-known example at Nelson's Battle of the Nile in 1798 and the birth of Mary Campbell during the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801. Rodger, p.506; Adkins, Jack Tar, pp. 176-7. The medical staff would have had no time to help them or give them comfort.

Rodger, p.506; Adkins, Jack Tar, pp. 176-7. The medical staff would have had no time to help them or give them comfort.

Forgot about Jane

Given that they experienced the same horror as the men and performed their tasks with equal bravery, the lack of attention and official recognition these women received must have been galling. As they were rarely, if ever, included on a ship's muster book, officially they did not exist and therefore received none of the plaudits and respect afforded their male counterparts. This makes it very hard to assess the level of their involvement based on most of the official sources available. Individual captains, while not listing women on the books, have left personal records that highlight the role of women in specific situations, such as the Bombardment of Algiers in 1816, where Admiral Edward Pellew proudly wrote of husbands and wives manning the same guns during the operation. Stephen Taylor, Commander: The Life and Exploits of Britain's Greatest Frigate Captain (London: Faber&Faber, 2012), p.288. Yet mainly the role of these women has gone unrecognised for far too long.

Stephen Taylor, Commander: The Life and Exploits of Britain's Greatest Frigate Captain (London: Faber&Faber, 2012), p.288. Yet mainly the role of these women has gone unrecognised for far too long.

Years after the end of the Anglo-French/Napoleonic warsThe Napoleonic Wars lasted from 1803 until 1815 (although some people also include the French Revolutionary Wars in this, which started in 1792 and continued until 1802. The Napoleonic Wars were therefore a continuation of the Revolutionary Wars). A number of European powers fought against the expansionist French Empire.The Napoleonic Wars lasted from 1803 until 1815 (although some people also include the French Revolutionary Wars in this, which started in 1792 and continued until 1802. The Napoleonic Wars were therefore a continuation of the Revolutionary Wars). A number of European powers fought against the…, Queen Victoria and her government introduced the Naval General Service Medal, to be given to all who had served in battle during those titanic conflicts. A few women did make the move to apply, having served onboard ship with all the bravery of their male counterparts. Yet they were denied this right. While initially members of the Admiralty did consider issuing these medals, they later changed their minds. It is quite likely that the Queen herself had prompted this, famously never having been behind the socio-political advancement of her fellow women and doubtless unnerved by the idea of female combatants in naval battles.

And therefore, until recently, the life and labours of Jane Tar have remained hidden from view, rarely studied by naval historians and equally rarely portrayed in the popular media that most commonly exposes people to the Age of Sail. It is valuable and extremely pleasing that this balance is now being righted, and that a gripping and fascinating story is finally being told.

Things to think about

- How does the lack of reporting of women at sea affect our understanding of the history of the period?

- What can be done, if anything, to recover the stories of women aboard ships?

- Have any films or documentaries ever caught the true horror of a battle at sea? Is there any way they ever could?

- What must life at sea and on land have been like for Jack and Jane Tar?

- What can be done to commemorate those unknown women who fought and lost their lives at sea?

Things to do

- There is next to nothing in the heritage industry that considers - or even references - the role of women in the Age of Sail. However, there are plenty of more general attractions for those interested in the wider history. The National Maritime Museum, at either Greenwich or Falmouth in Cornwall, covers British maritimeConnected with the sea, especially in relation to seaborne trade or naval matters. history from the earliest periods up to the present, and Portsmouth Historic Dockyard has some of the country's most important ships on display, including Nelson's Victory. There are also a number of other ships you can visit dotted around the country, including the 1816 HMS Trincomlee at Hartlepool and the 1824 HMS Unicorn at Dundee.

- For those interested in the land-side of the Age of Sail, try Buckler's Hard in Hampshire.

Things to read

The definite go-to book on this topic is Suzanne Stark's Female Tars. It covers all of the stories and issues in this article, but, of course, in far greater depth. It is an easy and enjoyable read and is highly recommended.

For an absolutely brilliant and very readable look at the whole period, nothing is better than Stephen Taylor's Sons of the Waves. While it naturally focuses on Jack Tar rather than his female counterpart, it creates the best and most approachable sense of the world onboard ships as experienced by normal seamen. Another interesting read on the Jack Tars is Roy and Lesley Adkins's Jack Tar.

For a more exhaustive and academic look at the period in question, N.A.M. Taylor's The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649-1815 is a good read, covering everything from shipboard life and battles to politics and administration.

Title image © National MaritimeConnected with the sea, especially in relation to seaborne trade or naval matters. Museum, Greenwich, London.

- Log in to post comments