Mary Queen of Scots: Woman and Queen

Key facts about Mary Queen of Scots

- Mary Queen of Scots was queen of Scotland and France

- She had three husbands: François II of France, Lord Darnley, and the earl of Bothwell

- She was forced to abdicate the Scottish throne in 1567, and fled to England

- She was accused of complicity in the murder of her second husband, and of being an adulteress

- Her CatholicismThe faith and practices of the Roman Catholic Church., and her claim to the English throne, had turned Elizabeth's adviser, William Cecil, into her implacable enemy

- Mary was fully implicated in the Babington Plot to kill Elizabeth I and give Mary the English crown

- She was executed in 1587 and was painted as a Catholic martyr

People you need to know

- Archibald Campbell, earl of Argyll - leading ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. Reformation. politician and nobleman

- Catherine de' Medici - Mary's first mother-in-law and one of the most powerful women in sixteenth-century Europe

- William Cecil - politician and chief adviser to Elizabeth I throughout most of her reign

- Elizabeth I - ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. Reformation. queen of England from 1558 until 1603, daughter of Henry VIII by Anne Boleyn

- François II - son of Henri II and Catherine de' Medici, and first husband of Mary Queen of Scots, who ruled France from 1559 to 1560

- Charles Guise, cardinal of Lorraine - Mary of Guise's brother, uncle to Mary Queen of Scots and powerful French politician

- François, duke of Guise - Mary of Guise's brother, uncle to Mary Queen of Scots and powerful French politician

- Henri II - king of France from 1547 until 1559

- Henry VIII - 'tyrannical' king of England from 1509 until 1547

- Thomas Howard, duke of Norfolk - second cousin to the queen and powerful politician from a leading noble family

- James V - king of Scotland from 1513 until 1542; father of Mary Queen of Scots

- James Hepburn, earl of Bothwell - Mary's third husband, widely suspected of her second husband's murder

- Mary of Guise - wife and queen consort of James V, regentSomeone who rules a state in the absence of the monarch, because the monarch is a child, absent or incapacitated.Someone who rules a state in the absence of the monarchA king, queen, or emperor, because the monarch is a child, absent or incapacitated.Someone who rules a state in the absence of the monarchA king, queen, or emperor, because the monarch is a child, absent or incapacitated. for her daughter, Mary Queen of Scots, from 1554 until 1560

- Mary Queen of Scots - queen consort of France (1559-1560), and queen of Scotland (1542-1567), daughter of James V and Mary of Guise

- David Rizzio - low-born Savoyard, secretary and musician to Mary, and one of her personal favourites

- Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley - cousin to Mary Queen of Scots and her second husband, who was murdered in 1567

- James Stewart, earl of Moray - illegitimateIn terms of children, those born out of wedlock (to unmarried parents).In terms of children, those born out of wedlock (to unmarried parents).In terms of children, those born out of wedlock (to unmarried parents). son of James V, and therefore Mary Queen of Scot's half-brother

Mary Queen of Scots is an enigma. For the last four hundred and fifty years she has been presented as a romanticCharacterised by expressions of love; or an idealised way of looking at something; or someone who followed the Romantic artistic movement, that focused on individualism and emotion.Characterised by expressions of love; or an idealised way of looking at something; or someone who followed the Romantic artistic movement, that focused on individualismThe idea or practice of being self-reliant and individual; a sense of self; or favouring freedom of action for individuals over the dictates of a group or state. and emotion. Characterised by expressions of love; or an idealised way of looking at something; or someone who followed the RomanticCharacterised by expressions of love; or an idealised way of looking at something; or someone who followed the Romantic artistic movement, that focused on individualism and emotion. artistic movement, that focused on individualismThe idea or practice of being self-reliant and individual; a sense of self; or favouring freedom of action for individuals over the dictates of a group or state. and emotion. heroine, a Catholic martyr, a weak and feeble female used as a pawn by scheming men, and a murderer and adulteress. But despite the amount of ink that has been spilt on her, no-one as yet has been able to create a fully-convincing portrait of this famous and controversial Scottish queen. Instead, we are left with a number of intriguing – and by-and-large unanswerable – questions. Was she a complete idiot in her choice of men or was she forced into a corner; did she have a hand in the death of her second husband; and, above all, was she a successful queen, doing her best in a bad situation, or was her life in fact ‘a study in failure’? Jenny Wormald, Mary Queen of Scots: A Study in Failure (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2017).

Jenny Wormald, Mary Queen of Scots: A Study in Failure (Edinburgh: John Donald, 2017).

Child queen

Princess Mary, the only surviving legitimate offspring of James V, became queen of Scotland when she was just six days old. According to many sources, her father, having suffered defeat at the hands of the English at the Battle of Solway Moss on 24 November 1542, died of a broken heart, but not before he’d allegedly uttered a prophecy about the Stewart/Stuart dynastyA line of hereditary rulers of a country, business, etc.A line of hereditary rulers of a country, business, etc. A line of hereditary rulers of a country, business, etc. : ‘it came wi’ a lass, it'll gang wi’ a lass’. The prophecy related to the accessionThe attainment or acquisition of a position of rank or power, often related to the throne.The attainment or acquisition of a position of rank or power, often related to the throne. The attainment or acquisition of a position of rank or power, often related to the throne. of the Stewarts to the throne through Robert the Bruce’s daughter, and James obviously thought it would finish with his own daughter. In this respect he was wrong, but otherwise it proved to be accurate: the last Stuart monarchA king, queen, or emperor was Queen Anne. It was not long before the infant queen was attracting problems, aside from her howling through the coronationThe ceremony of crowning a king or queen (and their consort).The ceremony of crowning a king or queen (and their consort).The ceremony of crowning a king or queen (and their consort). ceremony: in 1543, the ever-acquisitive Henry VIII took an active interest in her ‘welfare’. On 1 July of that year, peace and marriage – between Mary and Henry’s son Prince Edward – were agreed between the two old enemies at Greenwich. Under the terms of the treaty, Mary would transfer to the English court when she turned ten, effectively uniting Scotland and England in peace and harmony. But this wasn’t enough for Henry. Always an impatient bully, he began seizing Scottish shipping and pestering to have Scottish castles handed over even as the treaty was being negotiated. It is hardly surprising, then, that the treaty was rejected by the Scottish parliament in December 1543.

According to many sources, her father, having suffered defeat at the hands of the English at the Battle of Solway Moss on 24 November 1542, died of a broken heart, but not before he’d allegedly uttered a prophecy about the Stewart/Stuart dynastyA line of hereditary rulers of a country, business, etc.A line of hereditary rulers of a country, business, etc. A line of hereditary rulers of a country, business, etc. : ‘it came wi’ a lass, it'll gang wi’ a lass’. The prophecy related to the accessionThe attainment or acquisition of a position of rank or power, often related to the throne.The attainment or acquisition of a position of rank or power, often related to the throne. The attainment or acquisition of a position of rank or power, often related to the throne. of the Stewarts to the throne through Robert the Bruce’s daughter, and James obviously thought it would finish with his own daughter. In this respect he was wrong, but otherwise it proved to be accurate: the last Stuart monarchA king, queen, or emperor was Queen Anne. It was not long before the infant queen was attracting problems, aside from her howling through the coronationThe ceremony of crowning a king or queen (and their consort).The ceremony of crowning a king or queen (and their consort).The ceremony of crowning a king or queen (and their consort). ceremony: in 1543, the ever-acquisitive Henry VIII took an active interest in her ‘welfare’. On 1 July of that year, peace and marriage – between Mary and Henry’s son Prince Edward – were agreed between the two old enemies at Greenwich. Under the terms of the treaty, Mary would transfer to the English court when she turned ten, effectively uniting Scotland and England in peace and harmony. But this wasn’t enough for Henry. Always an impatient bully, he began seizing Scottish shipping and pestering to have Scottish castles handed over even as the treaty was being negotiated. It is hardly surprising, then, that the treaty was rejected by the Scottish parliament in December 1543.

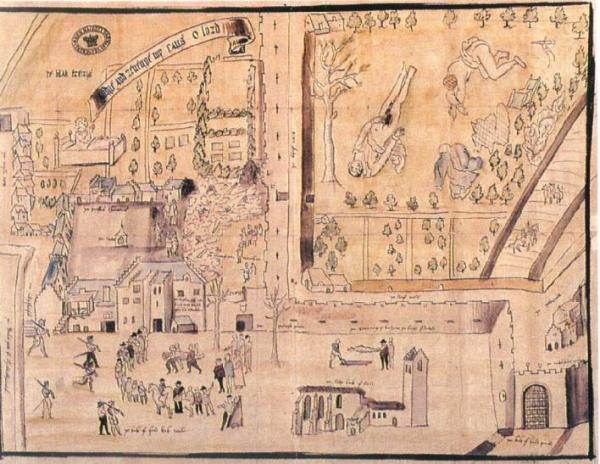

The backlash from Henry was severe. In the resultant ‘Rough Wooing’, he aimed to get by force what he could not get by peace. He declared war on Scotland and launched a series of raids against the country, instructing the earl of Hertford, who was leading the attack:

... to put all to fire and sword, burn Edinburgh town, so used and defaced, that when you have gotten what you can of it, it may remain forever a perpetual memory of the vengeance of God lighted upon it, for their falsehood and disloyalty … Sack Leith, and subvert it, and all the rest, putting man, woman, and child to fire and sword, without exception, when any resistance shall be made against you.

Privy CouncilA monarch's private advisers.A monarch's private advisers.A monarch's private advisers. to Hertford, 10 April 1544, Add. MS. 32,654, f. 80. BM Hamilton Papers, ii., No. 207. Calendared at British History Online, 314 https://www.british-history.ac.uk/letters-papers-hen8/vol19/no1/pp178-200.

It did not push the Scots into submission, but had quite the opposite effect: in August 1548 Mary was betrothed to the four-year-old Dauphin, François, in France.

French queen

Mary was thus to be raised as a child of the French royal family. Her education was ‘courtly rather than academic’, including music, dancing, needlework, and horsewomanship, and gave her many of her life-long loves. Julian Goodare, ‘Mary [Mary Stewart] (1542–1587), queen of Scots’ at Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, [accessed 12 Dec. 2018] at http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-18248 (hereafter DNB). ‘A delightful upbringing for the future queen consort of France’ it might have been, as Jenny Wormald noted, ‘but not one which at first sight looks like adequate preparation for the future queen regnant of Scotland.’

Julian Goodare, ‘Mary [Mary Stewart] (1542–1587), queen of Scots’ at Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, [accessed 12 Dec. 2018] at http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-18248 (hereafter DNB). ‘A delightful upbringing for the future queen consort of France’ it might have been, as Jenny Wormald noted, ‘but not one which at first sight looks like adequate preparation for the future queen regnant of Scotland.’ Nor it seems was the education good enough for any of Henri II’s three sons who each went on to become king, for, as Wormald points out, none was ‘in any way an impressive or successful ruler’. Wormald, pp. 73-4. Perhaps it was this lack of preparation that led Mary, in 1558, to sign away her Scottish kingdom to France if she had no children and as a pledge for reimbursement for her upbringing and for France’s military intervention in Scottish affairs. She might even have been forced into it by her French relatives – the duke of Guise and the cardinal of Lorraine, both of whom were her maternal uncles – but it hinted at disregard for her native country and made obvious her naivety and lack of statesmanship.

Nor it seems was the education good enough for any of Henri II’s three sons who each went on to become king, for, as Wormald points out, none was ‘in any way an impressive or successful ruler’. Wormald, pp. 73-4. Perhaps it was this lack of preparation that led Mary, in 1558, to sign away her Scottish kingdom to France if she had no children and as a pledge for reimbursement for her upbringing and for France’s military intervention in Scottish affairs. She might even have been forced into it by her French relatives – the duke of Guise and the cardinal of Lorraine, both of whom were her maternal uncles – but it hinted at disregard for her native country and made obvious her naivety and lack of statesmanship.

On 30 June 1559, King Henri II of France participated in a joustA competition in which two opponents on horseback fought with lances.A competition in which two opponents on horseback fought with lancesLong weapons with wooden shafts used by horsemen when charging their opponents..A competition in which two opponents on horseback fought with lancesLong weapons with wooden shafts used by horsemen when charging their opponents.. held to mark the conclusion of war with his Habsburg rivals, but celebration quickly turned into devastation. Henri’s opponent’s lance shattered on the king’s armour, with shards flying under his visor. One splinter pierced Henri’s forehead, another went through his left eye. The king lay brain damaged for ten days, suffering paralysis and convulsions, before dying of a massive stroke. Mary Queen of Scots had become queen consort of France. But the French claimed she was also queen elsewhere. Habitual enemies of England, and encouraged by the recent death of Catholic Mary Tudor, they quartered the arms of England and Ireland with those of Scotland and France. The statement was clear: Mary was queen of England. In 1558, Elizabeth I, who was widely regarded in Catholic countries as illegitimate, succeeded to the throne of England and Ireland. As a bastard – and ignoring the will of Henry VIII and the Act of Succession 1543 – Elizabeth had less right to the English throne than her cousin, who was descended from Margaret Tudor, Henry VIII’s sister. It was hardly a good start to Mary and Elizabeth I’s relationship as cousin-queens.

In 1558, Elizabeth I, who was widely regarded in Catholic countries as illegitimate, succeeded to the throne of England and Ireland. As a bastard – and ignoring the will of Henry VIII and the Act of Succession 1543 – Elizabeth had less right to the English throne than her cousin, who was descended from Margaret Tudor, Henry VIII’s sister. It was hardly a good start to Mary and Elizabeth I’s relationship as cousin-queens.

King François II was only fifteen at his accession, and – more importantly – was inexperienced and in fragile health. So it fell to Mary’s uncles to rule, with their niece and her husband little more than figureheads. Yet the Guises – considered interlopers by many – were not popular, and their brief reign as regents led to religious strife and revolt. It is not surprising, then, that when François died just seventeen months after his accession, the Guises and their niece fell from favour. François died from an ear condition of unknown cause. The Guises left court and Mary, although dithering in the hope of acquiring a second continental husband, was strongly encouraged by her mother-in-law, the indomitable Catherine de’ Medici, to return home.

François died from an ear condition of unknown cause. The Guises left court and Mary, although dithering in the hope of acquiring a second continental husband, was strongly encouraged by her mother-in-law, the indomitable Catherine de’ Medici, to return home.

Scottish queen

Home for the Scottish queen, though, was France, and furthermore, Scotland had changed since she’d left. The Lords of the Congregation – ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. rebels led by Mary’s illegitimate half-brother, James Stewart, and the earl of Argyll – had overthrown the Catholic church and the Francophile regency regime led by Mary of Guise, with the help of Elizabeth I’s adviser, William Cecil. Mary of Guise herself had died of dropsy in June 1560 and a treaty had been finalised between the French and English – with the assent of the Lords of the Congregation – the following month, without the agreement of either Mary. This Treaty of Edinburgh allowed for peace between England and France, and the withdrawal of both nations’ troops from Scotland, wherein they had been used for and against the Lords. But more importantly for Mary, it acknowledged Elizabeth’s right as queen, thus nullifying Mary’s claim to the English throne, and demanded that she ‘abstain from using and bearing the said title and arms of the kingdom of England or Ireland’. Treaty of Edinburgh, 6 July 1560, translated from the Latin at Wikisource, https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Edinburgh [accessed 7 February 2019].

Treaty of Edinburgh, 6 July 1560, translated from the Latin at Wikisource, https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Edinburgh [accessed 7 February 2019].

Mary landed back in Scotland on 19 August 1561 – over a year after her regent had died – and proceeded to Edinburgh. Before leaving she turned down the offer of Catholic lords for a landing at Aberdeen that would allow her to gather forces to unseat the Lords of the Congregation and restore the Catholic faith. Maybe having already had enough of sea-faring, Mary’s initial policy was not to rock the boat, but to be tolerant and maintain the status quo,

Before leaving she turned down the offer of Catholic lords for a landing at Aberdeen that would allow her to gather forces to unseat the Lords of the Congregation and restore the Catholic faith. Maybe having already had enough of sea-faring, Mary’s initial policy was not to rock the boat, but to be tolerant and maintain the status quo, On her journey to Scotland, one of the boats in the flotilla carrying all her baggage was badly steered into another, which sank with no survivors, despite Mary offering generous rewards for anyone who saved the drowning men. Mary took this as a bad omen. utilising her privy councilA monarch's private advisers.A monarch's private advisers. to create ‘a broad coalition of advisers’ that balanced the factions.

On her journey to Scotland, one of the boats in the flotilla carrying all her baggage was badly steered into another, which sank with no survivors, despite Mary offering generous rewards for anyone who saved the drowning men. Mary took this as a bad omen. utilising her privy councilA monarch's private advisers.A monarch's private advisers. to create ‘a broad coalition of advisers’ that balanced the factions. John Guy, My Heart is my Own: The Life of Mary Queen of Scots (London: Harper Perennial, 2004), p. 172. In this, at least at the beginning, she was reasonably successful, helped by her half-brother (whom she made earl of Moray in 1562). But this was not necessarily the result of political wisdom; rather it was a reflection of the early modern belief that female rulers needed male counsel. In fact, Mary only infrequently attended the council, instead preferring to surround herself with mainly-Catholic personal advisers. It would seem that Mary did not like challenge. When John Knox, the driving force behind the Scottish Reformation, for example, was commanded to attend an audience with Mary, she left the meeting in tears.

John Guy, My Heart is my Own: The Life of Mary Queen of Scots (London: Harper Perennial, 2004), p. 172. In this, at least at the beginning, she was reasonably successful, helped by her half-brother (whom she made earl of Moray in 1562). But this was not necessarily the result of political wisdom; rather it was a reflection of the early modern belief that female rulers needed male counsel. In fact, Mary only infrequently attended the council, instead preferring to surround herself with mainly-Catholic personal advisers. It would seem that Mary did not like challenge. When John Knox, the driving force behind the Scottish Reformation, for example, was commanded to attend an audience with Mary, she left the meeting in tears.

This tendency to cry when challenged was hardly the sign of a good sovereign. Nor were her several instances of stress-related illness and her ‘fatal political weakness of collapsing in times of trouble’. Wormald, p. 9. Well might she have been hampered by her gender, but instead of overcoming the perceived weaknesses of the female sex with astute political strategies and actions – as her cousin did – she played up to the stereotype. An inability to deal with stress and a propensity to burst into tears fit this stereotype, as did her love of dancing and singing over the business of state. But, more than anything else, it was her second and third marriages that played into her critics’ hands.

Wormald, p. 9. Well might she have been hampered by her gender, but instead of overcoming the perceived weaknesses of the female sex with astute political strategies and actions – as her cousin did – she played up to the stereotype. An inability to deal with stress and a propensity to burst into tears fit this stereotype, as did her love of dancing and singing over the business of state. But, more than anything else, it was her second and third marriages that played into her critics’ hands.

King and queen

The duty of a queen was to marry and produce an heir. This is the one sovereign duty that Mary did, and Elizabeth did not do, correctly. But Elizabeth might well have understood the pitfalls of a queen regnant marrying better than her cousin. A woman, no matter what her estate, was expected to obey her husband. This presented a reigning monarch with several problems. If she married someone of her own rank, he would be a king or prince in his own right, which would affect foreign policy and quite probably lead to an absent monarch. If she married one of her own subjects, not only would she be marrying below her station, but she would also be allying herself with a faction. And, as Elizabeth realised, once the queen produced – or in the English queen’s case, named – an heir, then that heir could provide a rallying point for political dissidents. History had provided precedents, and the religious upheavals of the sixteenth century ensured there was no shortage of causes for usurping a reigning monarch. Mary was to discover this to her detriment.

The queen had started looking for a second husband within a year of her first husband’s death. She had already thought about Charles IX, the ten-year old brother and successor to her first husband, but his mother disapproved of the match. She also considered Don Carlos, the mad heir-apparent of the Spanish Philip II, which Catherine de’ Medici also blocked. Carlos had made many murder attempts on people great and small, including ordering a house to be set on fire merely because he’d been splashed by some water from one of its windows. He was eventually imprisoned by his father in 1568, and died a year later. In 1563, she re-opened marriage negotiations with the Spanish king, provoking concern both at home and abroad. Elizabeth in particular considered the marriage a hostile act and, in the hopes of preventing this and other unsuitable marriages, proposed her own favourite, Robert Dudley, as a suitor.

She had already thought about Charles IX, the ten-year old brother and successor to her first husband, but his mother disapproved of the match. She also considered Don Carlos, the mad heir-apparent of the Spanish Philip II, which Catherine de’ Medici also blocked. Carlos had made many murder attempts on people great and small, including ordering a house to be set on fire merely because he’d been splashed by some water from one of its windows. He was eventually imprisoned by his father in 1568, and died a year later. In 1563, she re-opened marriage negotiations with the Spanish king, provoking concern both at home and abroad. Elizabeth in particular considered the marriage a hostile act and, in the hopes of preventing this and other unsuitable marriages, proposed her own favourite, Robert Dudley, as a suitor. She made him earl of Leicester – reportedly tickling his neck during the ceremony – in preparation. It is not quite known how Elizabeth envisaged the marriage, although it has been suggested that she expected the married couple to live at her court in a strange ménage à trois. But Dudley seemed about as enthusiastic towards the match as Mary, and, despite Elizabeth’s efforts, it was a non-starter. Mary, as Elizabeth quipped, ‘like[d] better of yonder long lad’: Lord Darnley.

She made him earl of Leicester – reportedly tickling his neck during the ceremony – in preparation. It is not quite known how Elizabeth envisaged the marriage, although it has been suggested that she expected the married couple to live at her court in a strange ménage à trois. But Dudley seemed about as enthusiastic towards the match as Mary, and, despite Elizabeth’s efforts, it was a non-starter. Mary, as Elizabeth quipped, ‘like[d] better of yonder long lad’: Lord Darnley. Cited in Helen Castor, Elizabeth: A Study in Insecurity (London: Penguin, 2018), p. 49.

Cited in Helen Castor, Elizabeth: A Study in Insecurity (London: Penguin, 2018), p. 49.

Henry Stewart, Lord Darnley, was young, handsome, and charming. Although some historians suggest that the initial flirtations with him were designed to rile Elizabeth into offering Mary the English succession, Mary quickly became infatuated with Darnley and they married on 29 July 1565. Darnley, Mary’s cousin, also had Tudor blood and as a result a claim to the English throne. Although his claim was no better than Mary’s, he did have one advantage: as he had been born in England, he was not the ‘alien’ that Mary was. DNB Despite becoming pregnant early in the relationship and promising Darnley the crown matrimonial, it didn’t take long for problems to start. Darnley rapidly showed himself to be vain, offensive, and violent. As one observer wrote, ‘All people say that Darnley is too much addicted to drinking … and gave her [Mary] such words that she left the place in tears'.

Darnley, Mary’s cousin, also had Tudor blood and as a result a claim to the English throne. Although his claim was no better than Mary’s, he did have one advantage: as he had been born in England, he was not the ‘alien’ that Mary was. DNB Despite becoming pregnant early in the relationship and promising Darnley the crown matrimonial, it didn’t take long for problems to start. Darnley rapidly showed himself to be vain, offensive, and violent. As one observer wrote, ‘All people say that Darnley is too much addicted to drinking … and gave her [Mary] such words that she left the place in tears'. Sir William Drury, cited in Elaine Finnie Greig, ‘Stewart, Henry, duke of Albany [known as Lord Darnley] (1545/6–1567), second consort of Mary, queen of Scots’ at Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-26473 [accessed 7 February 2019]. This, of course, is another time when Mary fled in floods of tears, acting every part the typical female. Whether it was designed to provoke sympathy or not is beside the point: politicians don’t rule by sympathy alone. But more importantly, in marrying Darnley, Mary had allied herself with a faction and it is telling that only his father shouted ‘God save his grace’ at the proclamationA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importance of him as king. Rebellion, led by the earl of Moray, sparked within weeks, justified on the grounds of Mary’s ill-chosen foreign advisers and on the royal couple’s alleged intentions of restoring the Catholic faith, despite Darnley having stayed away from his own wedding mass.

Sir William Drury, cited in Elaine Finnie Greig, ‘Stewart, Henry, duke of Albany [known as Lord Darnley] (1545/6–1567), second consort of Mary, queen of Scots’ at Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-26473 [accessed 7 February 2019]. This, of course, is another time when Mary fled in floods of tears, acting every part the typical female. Whether it was designed to provoke sympathy or not is beside the point: politicians don’t rule by sympathy alone. But more importantly, in marrying Darnley, Mary had allied herself with a faction and it is telling that only his father shouted ‘God save his grace’ at the proclamationA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importance of him as king. Rebellion, led by the earl of Moray, sparked within weeks, justified on the grounds of Mary’s ill-chosen foreign advisers and on the royal couple’s alleged intentions of restoring the Catholic faith, despite Darnley having stayed away from his own wedding mass. Darnley was ‘fluid’ in his religion: he had been raised a Catholic, but professed whichever beliefs he thought would give him the greatest advancement. The English initially half-heartedly supported the rebels in what became known as the Chaseabout Raid, as both armies marched to and fro across Scotland without ever meeting in battle. But when it became clear that Mary’s forces were stronger, the English withdrew their support and left the rebels to fend for themselves. Most, including Moray, fled south to the country that had abandoned them, and a parliament was arranged to confirm their exile and – according to rumour – legalise the Catholic mass.

Darnley was ‘fluid’ in his religion: he had been raised a Catholic, but professed whichever beliefs he thought would give him the greatest advancement. The English initially half-heartedly supported the rebels in what became known as the Chaseabout Raid, as both armies marched to and fro across Scotland without ever meeting in battle. But when it became clear that Mary’s forces were stronger, the English withdrew their support and left the rebels to fend for themselves. Most, including Moray, fled south to the country that had abandoned them, and a parliament was arranged to confirm their exile and – according to rumour – legalise the Catholic mass. On reaching England, Moray was publicly told to turn around and leave, as Elizabeth would not countenance a rebel in her kingdom.

On reaching England, Moray was publicly told to turn around and leave, as Elizabeth would not countenance a rebel in her kingdom.

This was the last straw for many; something had to be done to take control of the situation, and of Mary. The plotters needed a way in and a scapegoatA person who is blamed for the wrongdoings, mistakes, or faults of others.A person who is blamed for the wrongdoings, mistakes, or faults of others.A person who is blamed for the wrongdoings, mistakes, or faults of others., and lighted upon the rumoured inappropriate relationship between the queen and her low-born Savoyard secretary and musician, David Rizzio. Not stable at the best of times, Darnley had become increasingly jealous of this relationship and, frustrated by Mary’s continuing refusal to grant him full monarchical rights, was drawn into the plot with the promise of the crown matrimonial as bait. On 9 March 1566, Mary was sat down to supper with Rizzio and a few other friends in her personal chambers when a group of men led by Darnley entered. Darnley seized his wife while Rizzio was dragged pleading from the room. Outside, he was stabbed fifty-six times, with Darnley’s dagger left on the corpse: there was to be no doubt that Darnley was involved. The palace gates were barred and parliament was ordered to disperse. Mary was a prisoner.

Given the high levels of stress, Mary’s pregnancy, and her belief that she was the intended victim, it is a wonder the queen didn’t fall to pieces. Instead, in captivity she turned Darnley, pointing out to him that the lords would never give him the crown and assuring him of her continuing affection. Together they convinced the plotters to concede on the promise of a pardon, but while it was being drafted Mary and Darnley escaped to the easily-defensible fortress at Dunbar. At the head of an army raised by the earl of Bothwell, Mary swept back to power. The plot had achieved its aims – parliament did not reassemble and the Chaseabout lords were pardoned – but the plotters themselves fled to England, although not before revenging themselves on Darnley: they sent Mary the bond that fully implicated him in the murder. Less than a year later – on 10 February 1567 – Darnley was dead, discovered suffocated but unaffected by the explosion that had blown apart his lodging forty feet away from where he was found. Three months after that, Darnley’s widow married the chief suspect in his murder.

Killer Queen?

The ‘whodunnit’ mystery has intrigued generations since. The problem is that there is ‘a large cast of suspects since almost everyone had a motive to kill him.’ DNB Darnley had destabilised the kingdom, betrayed fellow plotters, and betrayed his wife. The only one who seemed to miss him was his father, the earl of Lennox, who demanded quick action. In response to Lennox’s request, the prime suspect, Bothwell, was given what just about passed as a trial but was cleared. It looked as if the murder would be quietly forgotten, until the plot thickened. On 24 April 1567, Mary was riding back from visiting her son when she was suddenly accosted at Bridge of Almond. She called to her servants to fetch help, but was taken captive and carried to Dunbar, where she was held for twelve days. Her attacker was Bothwell. Hereafter, accounts diverge. According to Mary’s story, she was raped: ‘we found his doings rude’, but on reviewing her options, she found that:

DNB Darnley had destabilised the kingdom, betrayed fellow plotters, and betrayed his wife. The only one who seemed to miss him was his father, the earl of Lennox, who demanded quick action. In response to Lennox’s request, the prime suspect, Bothwell, was given what just about passed as a trial but was cleared. It looked as if the murder would be quietly forgotten, until the plot thickened. On 24 April 1567, Mary was riding back from visiting her son when she was suddenly accosted at Bridge of Almond. She called to her servants to fetch help, but was taken captive and carried to Dunbar, where she was held for twelve days. Her attacker was Bothwell. Hereafter, accounts diverge. According to Mary’s story, she was raped: ‘we found his doings rude’, but on reviewing her options, she found that:

this realm, being divided in factions as it is, cannot be contained in order unless our authority be assisted and set forth by the fortification of a man, who must take pain upon his person in the execution of justice and suppressing of their insolence that would rebel, the travailPainful or hard effort. It can also refer to a woman in childbirth.Painful or hard effort. It can also refer to a woman in childbirth.Painful or hard effort. It can also refer to a woman in childbirth. whereof we may no longer sustain in our own person…’

Mary’s instructions to the bishop of Dunblane as ambassador to France, cited in Guy, pp. 357-62.

Bothwell kept on the pressure until ‘he partly extorted and partly obtained our promise to take him to our husband’. Ibid.

Ibid.

The other story, provided by the group that soon became known as the Lords Confederate and that was taken up enthusiastically by William Cecil, was that the abduction was contrived: Mary and Bothwell had been having an affair while Mary was still married to Darnley. This is rather disingenuous: Bothwell had met many of the Confederate Lords at Ainslie’s Tavern on 20 April 1567, before the abduction, and asked them to sign a bond giving him permission to pursue the queen in marriage, which they did (albeit perhaps grudgingly). This turned Darnley’s assassination from the cruel but necessary removal of a political liability, beneficial to everyone (but Darnley), into a brutal and impassioned murder by an adulteress and her lover. It also removed the unfortunate reality of the Lords’ complicity in his murder.

This is rather disingenuous: Bothwell had met many of the Confederate Lords at Ainslie’s Tavern on 20 April 1567, before the abduction, and asked them to sign a bond giving him permission to pursue the queen in marriage, which they did (albeit perhaps grudgingly). This turned Darnley’s assassination from the cruel but necessary removal of a political liability, beneficial to everyone (but Darnley), into a brutal and impassioned murder by an adulteress and her lover. It also removed the unfortunate reality of the Lords’ complicity in his murder.

It is more than likely that Mary had a hand in Darnley’s death. Mary and Bothwell, among others, met at Craigmillar castle in November 1566 to discuss the Darnley problem, where they ruled out divorce or annulment, which would affect the legitimacy of Mary’s son. Mary certainly felt relieved afterwards, and acted as such, observing mourning for an obscenely-short length of time, and attending a wedding before she did so. But whether she acted out of romantic interest is another matter. That she married Bothwell so swiftly is suspicious, and downright stupid. But the only real evidence for an affair, provided by the infamous Casket Letters delivered by Moray to Cecil during Mary’s hearing in England, is unconvincing. Twenty-two documents were presented to Cecil – including eight ‘damning’ letters – many of which look very much like forgeries, while others look to have been genuine letters by Mary spliced together or written at a different time. For a detailed discussion, see Guy, ch.25-6.

For a detailed discussion, see Guy, ch.25-6.

Whether Mary had been raped or no, she fully committed to her marriage once it had happened. When the Confederate Lords rebelled, the newly-pregnant Mary rode out with her husband to meet them, on 15 June 1567 at Carberry Hill. Her army held the higher ground, which would usually have been advantageous, but the day was warm. The Lords downhill were better shaded and had ready access to a cooling stream. As the Lords’ forces watched and waited in relative comfort, Mary’s army cooked in their armour and grew increasingly thirsty. Offers of single combat were given, but Bothwell deemed no-one good enough for his honour. Eventually provisions arrived for those in the baking heat, but instead of the wished-for water, they received wine. Thirst made them drink heavily, but they grew more dehydrated, as well as more and more drunk. And, as armies are wont to do, they started disappearing. Eventually, with Mary’s army dwindling rapidly, combat was agreed between one of the Confederate Lords and Bothwell. Bothwell should have won the fight – he was a border lord and a pirate, used to battle and fit – but Mary at the last moment intervened. She surrendered on two conditions: that Bothwell be allowed to leave, and that she be treated honourably.

Martyr queen?

Bothwell did escape, but Mary was not handled honourably, perhaps because she haughtily lectured her captors, inspiring their ill will: she was returned to Edinburgh and paraded through streets of soldiers who shouted ‘burn the whore’. It is likely that this show of disapproval was contrived. Bothwell made it to Norway, where he was recognised by a kinsman of a woman he’d dallied with and was thrown in prison. He died there – Guy says of excessive drinking – on 14 April 1578. From there she was taken to the island fortress of Lochleven, where she was lectured for two solid days by her half-brother and forced to abdicate in favour of her young son, James.

It is likely that this show of disapproval was contrived. Bothwell made it to Norway, where he was recognised by a kinsman of a woman he’d dallied with and was thrown in prison. He died there – Guy says of excessive drinking – on 14 April 1578. From there she was taken to the island fortress of Lochleven, where she was lectured for two solid days by her half-brother and forced to abdicate in favour of her young son, James. Who became James VI of Scotland and, eventually, James I of England. Mary never obtained the English throne, but her issue did; a small victory for her had she been alive to know it. Her half-brother became regent. Unsurprisingly, she also miscarried. Escape should theoretically have been impossible, but after one failed attempt, she eventually convinced the young sons of the laird of Lochleven to help her, one rowing her across the water and the other meeting her with some of the laird’s best horses on the other side.

Who became James VI of Scotland and, eventually, James I of England. Mary never obtained the English throne, but her issue did; a small victory for her had she been alive to know it. Her half-brother became regent. Unsurprisingly, she also miscarried. Escape should theoretically have been impossible, but after one failed attempt, she eventually convinced the young sons of the laird of Lochleven to help her, one rowing her across the water and the other meeting her with some of the laird’s best horses on the other side. Willie Douglas was probably the laird’s illegitimate son, George Douglas was a legitimate younger son. She attempted to retake the throne with superior forces at the Battle of Langside on 13 May 1568, but her commander, the earl of Argyll, fainted at a critical moment. Mary’s army fell apart and, instead of regrouping, she panicked and fled to England.

Willie Douglas was probably the laird’s illegitimate son, George Douglas was a legitimate younger son. She attempted to retake the throne with superior forces at the Battle of Langside on 13 May 1568, but her commander, the earl of Argyll, fainted at a critical moment. Mary’s army fell apart and, instead of regrouping, she panicked and fled to England.

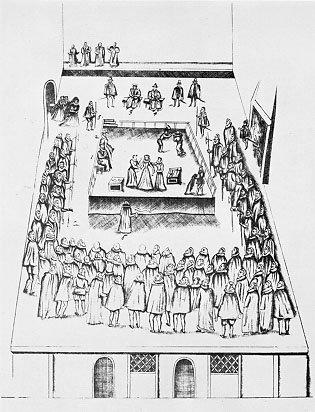

Her choice of refuge has received considerable criticism, and with good cause. Mary assumed that Elizabeth would do all she could to restore Mary to her throne, without realising that she’s placed her cousin in an impossible situation. With the northern English counties still Catholic, Mary’s entry into England could have precipitated lengthy and brutal civil wars on both sides of the border. Nor was the financially-prudent Elizabeth going to risk a potentially costly foreign war to put a Catholic monarch on a neighbouring country’s throne, particularly when that monarch had coveted the English crown. In an effort to resolve the situation amicably, Elizabeth arranged a hearing for both sides to present their case. Guy suggests that Elizabeth’s main reason for holding the hearing was to discover the extent to which the evidence against Mary had been forged. If anything, therefore, it perhaps should have been a trial of the Lords Confederate. (pp. 432-3) She had not intended it to be a trial of Mary, but that is what it became, with Cecil engineering the judges and preventing Mary from seeing the evidence – the Casket Letters – against her.

Guy suggests that Elizabeth’s main reason for holding the hearing was to discover the extent to which the evidence against Mary had been forged. If anything, therefore, it perhaps should have been a trial of the Lords Confederate. (pp. 432-3) She had not intended it to be a trial of Mary, but that is what it became, with Cecil engineering the judges and preventing Mary from seeing the evidence – the Casket Letters – against her.

Despite Cecil’s meddling, the hearing was inconclusive. Mary was to remain in England under closely-watched, but ‘royally luxurious’, house arrest, looked after by the earl of Shrewsbury and his wife, Bess of Hardwick. Castor, p. 58. She dined under her cloth of state and continued with her beloved needlework pursuits, and was even occasionally able to go hunting or enjoy the waters at Buxton.

Castor, p. 58. She dined under her cloth of state and continued with her beloved needlework pursuits, and was even occasionally able to go hunting or enjoy the waters at Buxton. It was not a particularly satisfactory arrangement for Shrewsbury, who effectively had to pay to feed and accommodate a permanent royal residence in his own household (both Mary and the English crown were meant to help, but did so only infrequently, and the financial burden was crippling). It also appears to have put strains on his marriage, which irrevocably broke down in 1585.

It was not a particularly satisfactory arrangement for Shrewsbury, who effectively had to pay to feed and accommodate a permanent royal residence in his own household (both Mary and the English crown were meant to help, but did so only infrequently, and the financial burden was crippling). It also appears to have put strains on his marriage, which irrevocably broke down in 1585.

Yet this half-life did not satisfy Mary, who suffered bouts of ill health throughout her captivity. Reduced exercise, without a reduced diet, led to weight gain and, by the 1580s, she had such painful arthritis in her arms and legs that she was barely able to move. And she never gave up her desire to gain the Scottish – and possibly the English - throne. The association scheme, for example, proposed a joint reign with her son. James was never going to agree to the scheme: he’d just managed to establish himself as sole ruler after his lengthy minority, and there’s no way he would have given that up for a mother he couldn’t remember and about whom he’d heard such dreadful stories. There is some debate among historians over the complicity of Mary in the various plots against Elizabeth spanning the years 1569 to 1586 – Kate Williams, for example, says that ‘It’s quite clear that Mary didn’t plot against Elizabeth … right until the last minute’ – but Mary did not exactly discourage them.

The association scheme, for example, proposed a joint reign with her son. James was never going to agree to the scheme: he’d just managed to establish himself as sole ruler after his lengthy minority, and there’s no way he would have given that up for a mother he couldn’t remember and about whom he’d heard such dreadful stories. There is some debate among historians over the complicity of Mary in the various plots against Elizabeth spanning the years 1569 to 1586 – Kate Williams, for example, says that ‘It’s quite clear that Mary didn’t plot against Elizabeth … right until the last minute’ – but Mary did not exactly discourage them. Elinor Evans, ‘Did Elizabeth I and Mary Queen of Scots Really Meet?’ at History Extra, https://www.historyextra.com/period/elizabethan/did-elizabeth-i-mary-queen-scots-really-meet-film-why/ [accessed 17 January 2019]. In 1569, amidst the plot for the duke Norfolk and Mary to marry and succeed to the English throne, Mary declared to her intended that ‘I will live and die with you’: a clear statement of intent.

Elinor Evans, ‘Did Elizabeth I and Mary Queen of Scots Really Meet?’ at History Extra, https://www.historyextra.com/period/elizabethan/did-elizabeth-i-mary-queen-scots-really-meet-film-why/ [accessed 17 January 2019]. In 1569, amidst the plot for the duke Norfolk and Mary to marry and succeed to the English throne, Mary declared to her intended that ‘I will live and die with you’: a clear statement of intent. Castor, p. 60. Two years later, she was writing to a papal agent, Rudolph Ridolfi, requesting Spanish aid and deploring the French, while at the same time writing to both the French and Elizabeth for the same thing. There can be little doubt that her plea to Ridolfi led to the eponymous Ridolfi Plot, which intended to depose Elizabeth with the help of the Spanish and put Norfolk and Mary on the English throne.

Castor, p. 60. Two years later, she was writing to a papal agent, Rudolph Ridolfi, requesting Spanish aid and deploring the French, while at the same time writing to both the French and Elizabeth for the same thing. There can be little doubt that her plea to Ridolfi led to the eponymous Ridolfi Plot, which intended to depose Elizabeth with the help of the Spanish and put Norfolk and Mary on the English throne. Despite Mary’s prior declaration, she didn’t die with Norfolk, who was sent to the block in June 1572.

Despite Mary’s prior declaration, she didn’t die with Norfolk, who was sent to the block in June 1572.

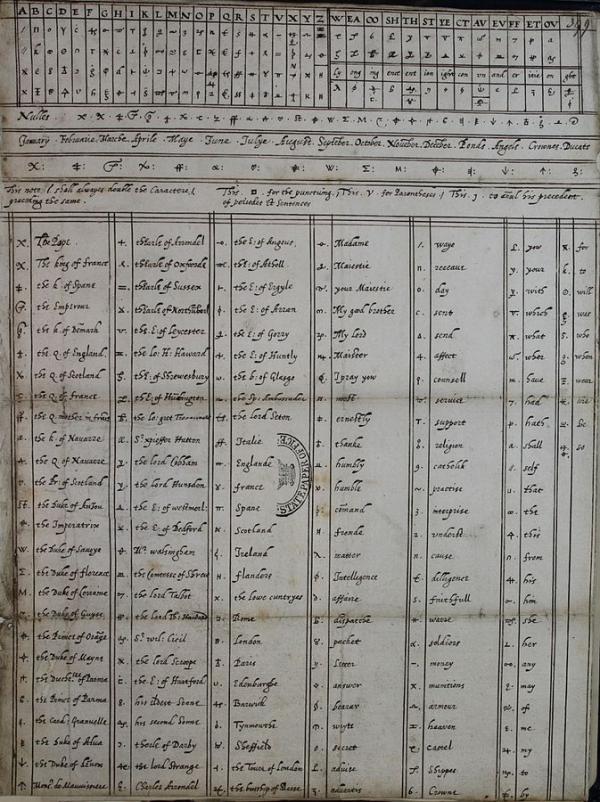

The problem for Cecil was there simply wasn’t enough evidence of Mary’s full involvement in any of the plots, at least until 1586, by which point Mary had been moved to the more careful custody of Amyas Paulet. Despite knowing she was being watched, she still felt secure enough to write coded letters to her fellow conspirators, in particular to Anthony Babington. What she couldn’t know is that letters both to and from her were being intercepted and decoded. The trap closed when, in response to Babington’s proposal ‘For the dispatch of the usurper … there be six noble gentlemen, all my private friends, who … will undertake that tragical execution’, Mary agreed that ‘The affairs being thus prepared and forces in readiness both without and within the realm, then shall it be time to set the six gentlemen to work’. Cited in Guy, p. 483. Despite its questionable legality, the outcome of the subsequent trial was a foregone conclusion. Yet Mary wasn’t executed straight away. It was only on 1 February 1587 that Elizabeth finally succumbed to pressure and signed the execution warrant. Even then, she was furious when the warrant was despatched.

Cited in Guy, p. 483. Despite its questionable legality, the outcome of the subsequent trial was a foregone conclusion. Yet Mary wasn’t executed straight away. It was only on 1 February 1587 that Elizabeth finally succumbed to pressure and signed the execution warrant. Even then, she was furious when the warrant was despatched. The problem for Elizabeth was the divine right of a monarchyThe king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head.The king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head.The king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head., and executing a queen set a dangerous precedent, the problems of which became only too obvious in 1649. She would have much rather had Mary quietly murdered, rather than an officially-sanctioned execution.

The problem for Elizabeth was the divine right of a monarchyThe king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head.The king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head.The king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head., and executing a queen set a dangerous precedent, the problems of which became only too obvious in 1649. She would have much rather had Mary quietly murdered, rather than an officially-sanctioned execution.

Mary’s execution took place at Fotheringhay Castle on 8 February 1587. She prepared well for it, managing to turn the last moments of her life into a fabulous propagandaBiased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view.Biased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view.Biased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view. coupA sudden, and often violent, illegal seizure of power from a government.A sudden, and often violent, illegal seizure of power from a government.A sudden, and often violent, illegal seizure of power from a government. for the Catholic cause. Having done very little to restore Catholicism in Scotland, she now painted herself as a martyr: her undergarments, when displayed, were red (the colour of Catholic martyrdom). She spoke over and commanded Richard Fletcher, dean of Peterborough, not to read his sermon, and loudly said her Catholic prayers first in Latin and, when the onlookers had been silenced, in English, before performing the Catholic sign of the cross and kissing her crucifix. It took three blows of the axe to sever her head from her body, but there was one final indignity left: when the executioner attempted to hold up Mary’s head, all he managed to grasp was her cap and a wig. Her head, with her thin grey hair, had remained where it was.

The foreign response to Mary’s execution was predictable: in Paris, crowds surrounded the LouvreOriginally a late-twelfth or early-thirteenth-century fortress in Paris, it became the main residence of the French kings in 1546. After Louis XIV moved his main residence to Versailles, it became a place to store the royal collection and later home to the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. The French National Assembly decreed it should become a museum and it opened in 1793. It is now the world's largest art museum.Originally a late-twelfth or early-thirteenth-century fortress in Paris, it became the main residence of the French kings in 1546. After Louis XIV moved his main residence to Versailles, it became a place to store the royal collection and later home to the Royal Academy of Painting and…Originally a late-twelfth or early-thirteenth-century fortress in Paris, it became the main residence of the French kings in 1546. After Louis XIV moved his main residence to Versailles, it became a place to store the royal collection and later home to the Royal Academy of Painting and… demanding revenge; in Spain, it finally prompted Philip II to launch his Armada; and in England there was rejoicing. The Scottish response was one of outrage and horror, and members of parliament swore to avenge her. But in the end, their words came to nothing. They, unlike their executed former queen, understood political realities. Mary is perceived as a romantic figure because that is how she saw herself, and how she acted. It is easy enough to feel sorry for the weak woman, thinking herself in love, feeling used and abandoned by those she – mistakenly – trusted, surrendering herself to tears and fits of despair, and surrounding herself by advisers who thought, spoke, and prayed as she did. But she lived in a dream world, of which she was the centre, and this is no way for a monarch to behave. Her political judgement was lacking, she was naïve and had little interest in the business of state, and she made some of the worst decisions a monarch could make. Yes, she was a woman in a man’s world, but there were plenty of examples of strong women even within her range of acquaintance – her own mother, Elizabeth I and Catherine de’ Medici being just a few. So, feel sympathy for the woman, but judge her differently as queen.

Things to think about

- How good a queen was Mary Queen of Scots?

- Was Mary Queen of Scots a victim, and in what ways?

- Did she have a hand in Darnley's death, and how likely was it that she was having an affair with Bothwell beforehand?

- Could anyone - male or female - have done better (or worse) as monarch of Scotland?

- How much luck features in Mary Queen of Scot's story?

- Did she deserve to die in the manner and for the reason that she did?

- How much of a threat was she to Elizabeth?

- How much did English actions contribute to the downfall of Mary as queen of Scotland?

Things to do

- Mary stayed at many places throughout her life. The best which you can still visit include the Palace of Holyroodhouse and Lochleven Castle in Scotland, and Carlisle Castle and Tutbury Castle in England.

- The National Archives has evidence on the Darnley murder through which you can work and draw your own conclusions. You can visit it here.

- The full text of the Casket Letters are in the appendices to T.F. Henderson's Mary Queen of Scots and the casket letters that is available on The Internet Archive. Read the evidence Moray provided to see whether you think Mary is guilty of adultery and murder.

Further reading

The range of books available on Mary Queen of Scots is daunting. One biography still considered to be among the best is Antonia Fraser's Mary Queen of Scots.

John Guy has written sympathetically on Mary in his My Heart is My Own, which neatly balances Jenny Wormald's very critical discussion of Mary Queen of Scot's statemanship in Mary Queen of Scots: A Study in Failure.

A more recent and accessible consideration of the relationship between Mary and Elizabeth can be found in Kate Williams' Rival Queens.

- Log in to post comments