The Puritan Threat?

Key facts about 'the puritanDescribing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism.Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of CatholicismThe faith and practices of the Roman Catholic Church.. Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of CatholicismThe faith and practices of the Roman Catholic Church. . Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of CatholicismThe faith and practices of the Roman Catholic Church. . Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of CatholicismThe faith and practices of the Roman Catholic Church. . threat'

- 'PuritanismThe beliefs of people who thought that the Protestant Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed.The beliefs of people who thought that the ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed.The beliefs of people who thought that the ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed.The beliefs of people who thought that the ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed.The beliefs of people who thought that the ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed.' can be taken to mean a lot of things, but it can generally be defined in the seventeenth century as the belief that the Church of England needed further reform.

- Puritans were committed to living in as 'godly' a fashion as possible, following closely the word of the Scriptures and translating that into behaviour and actions.

- They often saw themselves as a people apart, as members of the 'elect' destined to have a place in heaven.

- This separation and their emphasis on further reform could be seen as challenging the structures of society, the Church of England, and the monarchyThe king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head.The king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head.The king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head.The king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head.The king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head..

- Elizabeth I, James I, and Charles I were all wary of puritans and introduced various policies to curb puritan enthusiasm.

- However, Elizabeth and James had more political sense than Charles and sought a middle way.

- Charles made it obvious that he preferred anti-Calvinist rites and beliefs, and so forced moderate puritans into more extreme positions.

- The way the individual monarchs and their bishops responded to puritans therefore determined the level of threat posed by puritans.

People you need to know

- Charles I - son of James I, and king of England from 1625 until his execution for treason by the Rump of parliament in 1649

- Elizabeth I - daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, and queen of England from 1558 until 1603. Through her religious settlement she reintroduced protestantism to England following the reign of her Catholic half-sister, Mary I.

- James I - king of England from 1603 until 1625, and also James VI of Scotland (from 1567, after the deposition of his Catholic mother, Mary Queen of Scots, by a group of protestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation.Someone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation.Someone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation.Someone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. nobles).

- William Laud - Archbishop of Canterbury from 1633 until his execution in 1645. With help from Charles, he introduced a more ritualised and uniform version of Christianity to the Church of England, and questioned elements of Calvinist theory. His version of Christianity is often referred to as Laudianism.

Most historians now agree that there was no puritanDescribing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of CatholicismThe faith and practices of the Roman Catholic Church. . Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of CatholicismThe faith and practices of the Roman Catholic Church. . Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of CatholicismThe faith and practices of the Roman Catholic Church. . threat, either to the Church of England or to the state, in the early seventeenth century, and nor were the civil wars of the middle of the century a puritan revolution. But to those living in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the threat - or the promise - of puritan dominance seemed real. After all, AnglicanismThe faith and practices of the Church of England.The faith and practices of the Church of England. The faith and practices of the Church of England. The faith and practices of the Church of England. The faith and practices of the Church of England. The faith and practices of the Church of England. The faith and practices of the Church of England. The faith and practices of the Church of England. was a new religion, open to attacks from both sides; the power and position of the Church of England seemed precarious and in need of strong defence. A myth was built up and perpetuated by historiographyThe study of writing history, or of history that has already been written.The study of writing history, or of history that has already been written. The study of writing history, or of history that has already been written. The study of writing history, or of history that has already been written. The study of writing history, or of history that has already been written. The study of writing history, or of history that has already been written. The study of writing history, or of history that has already been written. The study of writing history, or of history that has already been written. that showed puritans as a dangerous group, seeking to turn the world upside down, to destroy the sacred position of the monarchA king, queen, or emperorA king, queen, or emperorA king, queen, or emperorA king, queen, or emperorA king, queen, or emperorA king, queen, or emperorA king, queen, or emperorA king, queen, or emperor as head of the church, and to question all divine-rightSanctioned by God.Sanctioned by God. Sanctioned by God. Sanctioned by God. Sanctioned by God. Sanctioned by God. Sanctioned by God. authority. Ultimately, it was this very need to protect the established church, rather than either CatholicismThe faith and practices of the Roman Catholic Church. or puritanismThe beliefs of people who thought that the Protestant Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed.The beliefs of people who thought that the Protestant Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed.The beliefs of people who thought that the Protestant Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed.The beliefs of people who thought that the Protestant Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed.The beliefs of people who thought that the ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed.The beliefs of people who thought that the ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed.The beliefs of people who thought that the ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed., that was its greatest threat. It was the fears of its most vehement supporters that challenged the church’s stability in the short-term, and which turned potential allies into enemies.

Inside or outside? Puritans and the established church

PuritanismThe beliefs of people who thought that the Protestant Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed.The beliefs of people who thought that the Protestant Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed.The beliefs of people who thought that the Protestant Reformation was incomplete and more reform was needed. was, and is, a nebulousHazy, vague, or ill-defined.Hazy, vague, or ill-defined. Hazy, vague, or ill-defined. Hazy, vague, or ill-defined. Hazy, vague, or ill-defined. Hazy, vague, or ill-defined. Hazy, vague, or ill-defined. Hazy, vague, or ill-defined. concept. At its most restrictive, it applies to those with reformistSupporting the European Reformation of religion, where Protestants split from Catholic beliefs and practices, or supporting reform in a more general way.Supporting the European Reformation of religion, where Protestants split from Catholic beliefs and practices, or supporting reform in a more general way.Supporting the European Reformation of religion, where Protestants split from Catholic beliefs and practices, or supporting reform in a more general way.Supporting the European Reformation of religion, where Protestants split from Catholic beliefs and practices, or supporting reform in a more general way.Supporting the European Reformation of religion, where Protestants split from Catholic beliefs and practices, or supporting reform in a more general way.Supporting the European Reformation of religion, where Protestants split from Catholic beliefs and practices, or supporting reform in a more general way.Supporting the European Reformation of religion, where Protestants split from Catholic beliefs and practices, or supporting reform in a more general way.Supporting the European Reformation of religion, where Protestants split from Catholic beliefs and practices, or supporting reform in a more general way. views who sat outside the established church. But most puritans chose to reform the church from within, and it was only in the 1630s, when further reformation had failed, that more groups separated. Despite this, investigators saw sectarianism everywhere. Groups meeting to discuss a sermon were considered dangerous conventiclesSecret or unlawful meetings, usually of nonconformists.Secret or unlawful meetings, usually of nonconformists. Secret or unlawful meetings, usually of nonconformists. Secret or unlawful meetings, usually of nonconformists. Secret or unlawful meetings, usually of nonconformists. Secret or unlawful meetings, usually of nonconformists. Secret or unlawful meetings, usually of nonconformists. Secret or unlawful meetings, usually of nonconformists. , and pamphlets listed the range of social as well as religious norms broken by separatists. But puritanism was wider than the nonconformingPeople, groups, or ideas not in agreement with established practices or beliefs.People, groups, or ideas not in agreement with established practices or beliefs. People, groups, or ideas not in agreement with established practices or beliefs. People, groups, or ideas not in agreement with established practices or beliefs. People, groups, or ideas not in agreement with established practices or beliefs. People, groups, or ideas not in agreement with established practices or beliefs. People, groups, or ideas not in agreement with established practices or beliefs. sects, and so should its definition be. Although disagreeing on many points, and changing over time, as a group puritans were fervent in their beliefs, heavily reliant on scripture, committed to further reformation and translating the word of God into the actions and behaviour of everyday life. It is this extremity of belief, and this inner certainty, that separated puritans from their contemporaries, and it is this definition that will be used here.

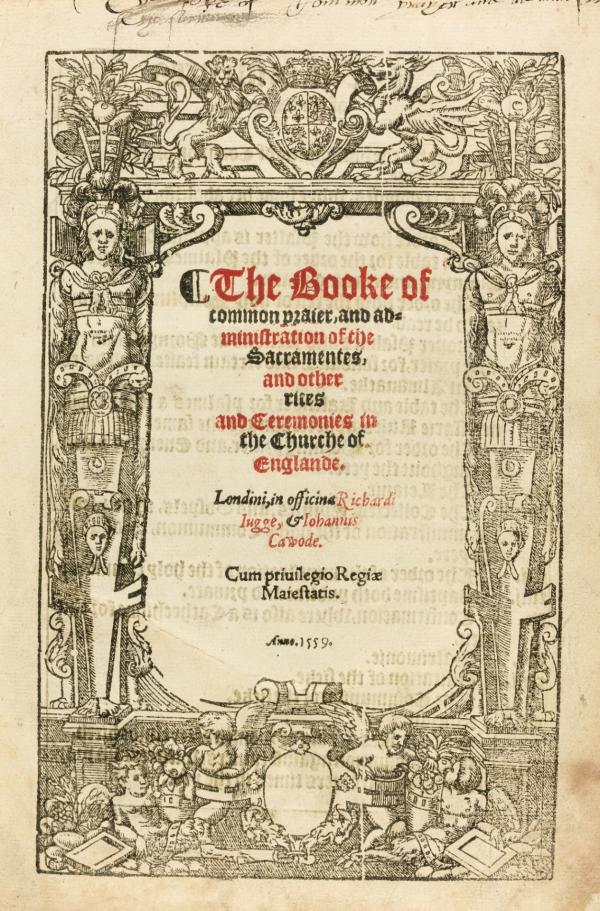

General puritan commitment to the church contributed to its stability, helping to fortify it against the perceived threat of Roman Catholicism. At the start of Elizabeth I’s reign, Marian exilesPeople who had fled England during the reign of Mary I.People who had fled England during the reign of Mary I. People who had fled England during the reign of Mary I. People who had fled England during the reign of Mary I. People who had fled England during the reign of Mary I. People who had fled England during the reign of Mary I. People who had fled England during the reign of Mary I. flocked back to England, with many taking positions in the new church despite their reservations over the nature of the compromise it represented. For these former exiles, the conservatism of the Elizabethan regime was a concern, as it encouraged the retention of vestmentsRobes worn by the clergy.Robes worn by the clergyThe people ordained for religious duties, especially in the Christian Church.. Robes worn by the clergyThe people ordained for religious duties, especially in the Christian Church. . Robes worn by the clergyThe people ordained for religious duties, especially in the Christian Church. . Robes worn by the clergyThe people ordained for religious duties, especially in the Christian Church. . Robes worn by the clergyThe people ordained for religious duties, especially in the Christian Church. . Robes worn by the clergyThe people ordained for religious duties, especially in the Christian Church. . and rites that, to those used to continental practice, smacked of popery. John Jewel wrote to the continental divine Peter Martyr ‘that it is idly and scurrilously said … that as heretofore Christ was cast out by his enemies, so he is now kept out by his friends.’ John Jewel to Peter Martyr, 14 April 1559, in Hastings Robinson (ed.), The Zurich letters: or, The correspondence of several English bishops and others with some of the Helvetian reformers during the reign of Queen Elizabeth: chiefly from the archives of Zurich (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1846), p. 28. Martyr, for his part, urged the returned exiles ‘not to withdraw yourself from the function offered you’, for 'if you sit at the helm of the church, there is a hope that many things may be corrected’.

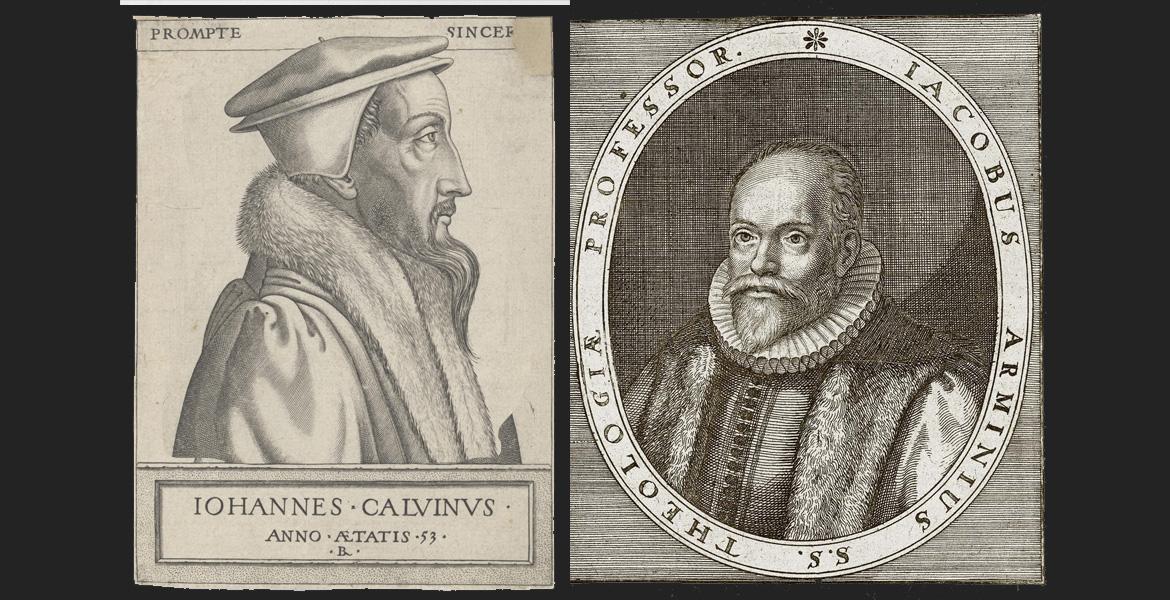

John Jewel to Peter Martyr, 14 April 1559, in Hastings Robinson (ed.), The Zurich letters: or, The correspondence of several English bishops and others with some of the Helvetian reformers during the reign of Queen Elizabeth: chiefly from the archives of Zurich (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1846), p. 28. Martyr, for his part, urged the returned exiles ‘not to withdraw yourself from the function offered you’, for 'if you sit at the helm of the church, there is a hope that many things may be corrected’. Peter Martyr to Thomas Sampson, 1 February 1560, in Hastings Robinson (ed.), The Zurich letters (2nd Series), Comprising the correspondence of several English bishops and others with some of the Helvetian reformers during the reign of Queen Elizabeth, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1845), pp. 38-9. Disagreement over adiaphora'Of things indifferent': practices or rites that are not central to a religion, especially to Christianity.'Of things indifferent': practices or rites that are not central to a religion, especially to Christianity. 'Of things indifferent': practices or rites that are not central to a religion, especially to Christianity. 'Of things indifferent': practices or rites that are not central to a religion, especially to Christianity. 'Of things indifferent': practices or rites that are not central to a religion, especially to Christianity. 'Of things indifferent': practices or rites that are not central to a religion, especially to Christianity. 'Of things indifferent': practices or rites that are not central to a religion, especially to Christianity. and the remnants of ‘popishness’ could destabilise the church, as evidenced by the Vestiarian ControversyThe uproar that happened in 1566 when 37 ministers were suspended for refusing to wear the surplice (clerical dress).The uproar that happened in 1566 when 37 ministers were suspended for refusing to wear the surplice (clerical dress). The uproar that happened in 1566 when 37 ministers were suspended for refusing to wear the surplice (clerical dress). The uproar that happened in 1566 when 37 ministers were suspended for refusing to wear the surplice (clerical dress). The uproar that happened in 1566 when 37 ministers were suspended for refusing to wear the surplice (clerical dress). The uproar that happened in 1566 when 37 ministers were suspended for refusing to wear the surplice (clerical dress). The uproar that happened in 1566 when 37 ministers were suspended for refusing to wear the surplice (clerical dress). , but it also contributed to the via media'Middle way' between two extremes.'Middle way' between two extremes. 'Middle way' between two extremes. 'Middle way' between two extremes. 'Middle way' between two extremes. 'Middle way' between two extremes. 'Middle way' between two extremes. that was to characterise it. The appointment of moderate puritan bishops continued into James I’s reign, to the point where, in Nicholas Tyacke’s opinion, the assimilation of puritanism had been so successful that ‘society [was] steeped in Calvinist theology’.

Peter Martyr to Thomas Sampson, 1 February 1560, in Hastings Robinson (ed.), The Zurich letters (2nd Series), Comprising the correspondence of several English bishops and others with some of the Helvetian reformers during the reign of Queen Elizabeth, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1845), pp. 38-9. Disagreement over adiaphora'Of things indifferent': practices or rites that are not central to a religion, especially to Christianity.'Of things indifferent': practices or rites that are not central to a religion, especially to Christianity. 'Of things indifferent': practices or rites that are not central to a religion, especially to Christianity. 'Of things indifferent': practices or rites that are not central to a religion, especially to Christianity. 'Of things indifferent': practices or rites that are not central to a religion, especially to Christianity. 'Of things indifferent': practices or rites that are not central to a religion, especially to Christianity. 'Of things indifferent': practices or rites that are not central to a religion, especially to Christianity. and the remnants of ‘popishness’ could destabilise the church, as evidenced by the Vestiarian ControversyThe uproar that happened in 1566 when 37 ministers were suspended for refusing to wear the surplice (clerical dress).The uproar that happened in 1566 when 37 ministers were suspended for refusing to wear the surplice (clerical dress). The uproar that happened in 1566 when 37 ministers were suspended for refusing to wear the surplice (clerical dress). The uproar that happened in 1566 when 37 ministers were suspended for refusing to wear the surplice (clerical dress). The uproar that happened in 1566 when 37 ministers were suspended for refusing to wear the surplice (clerical dress). The uproar that happened in 1566 when 37 ministers were suspended for refusing to wear the surplice (clerical dress). The uproar that happened in 1566 when 37 ministers were suspended for refusing to wear the surplice (clerical dress). , but it also contributed to the via media'Middle way' between two extremes.'Middle way' between two extremes. 'Middle way' between two extremes. 'Middle way' between two extremes. 'Middle way' between two extremes. 'Middle way' between two extremes. 'Middle way' between two extremes. that was to characterise it. The appointment of moderate puritan bishops continued into James I’s reign, to the point where, in Nicholas Tyacke’s opinion, the assimilation of puritanism had been so successful that ‘society [was] steeped in Calvinist theology’. Cited in Patrick Collinson, The Religion of Protestants: The Church in English Society 1559-1625 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982), p. 81. There is little sense, then, in declaring a puritan threat to the Church of England, when many moderate puritans were working for it. Furthermore, even the ‘hotter sort’, upon entering the episcopacyThe government of a church by bishops, or the office of a bishop.The government of a church by bishops, or the office of a bishop. The government of a church by bishops, or the office of a bishop. The government of a church by bishops, or the office of a bishop. The government of a church by bishops, or the office of a bishop. The government of a church by bishops, or the office of a bishop. The government of a church by bishops, or the office of a bishop. The government of a church by bishops, or the office of a bishop. , cooled when confronted with the difficulties of church governance and finance, and their own hopes of career progression.

Cited in Patrick Collinson, The Religion of Protestants: The Church in English Society 1559-1625 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982), p. 81. There is little sense, then, in declaring a puritan threat to the Church of England, when many moderate puritans were working for it. Furthermore, even the ‘hotter sort’, upon entering the episcopacyThe government of a church by bishops, or the office of a bishop.The government of a church by bishops, or the office of a bishop. The government of a church by bishops, or the office of a bishop. The government of a church by bishops, or the office of a bishop. The government of a church by bishops, or the office of a bishop. The government of a church by bishops, or the office of a bishop. The government of a church by bishops, or the office of a bishop. The government of a church by bishops, or the office of a bishop. , cooled when confronted with the difficulties of church governance and finance, and their own hopes of career progression.

Presbyterianism

But those puritans not dealing with political realities were frustrated by the lack of further reform, and therefore attacked the root of their disappointment: the episcopacy. These presbyterianRelating to a style of church governance that uses church elders rather than bishops, or people who belong to a presbyterian church.Relating to a style of church governance that uses church elders rather than bishops, or people who belong to a presbyterian church. Relating to a style of church governance that uses church elders rather than bishops, or people who belong to a presbyterian church. Relating to a style of church governance that uses church elders rather than bishops, or people who belong to a presbyterian church. Relating to a style of church governance that uses church elders rather than bishops, or people who belong to a presbyterian church. Relating to a style of church governance that uses church elders rather than bishops, or people who belong to a presbyterian church. Relating to a style of church governance that uses church elders rather than bishops, or people who belong to a presbyterian church. attacks in the first half of Elizabeth’s reign and the fate of episcopalianAdvocating government of a church by bishops.Advocating government of a church by bishops. Advocating government of a church by bishops. Advocating government of a church by bishops. Advocating government of a church by bishops. Advocating government of a church by bishops. Advocating government of a church by bishops. governance in the 1640s have been used by some to show not just the continuance, but the escalation, of puritan ‘opposition’. Under Elizabeth, the Archbishop of York Edwin Sandys wrote that bishops were considered, in Patrick Collinson’s phrase, ‘excrementum mundi’, while others observed that many ‘minds are entirely set against the bishops; for they scarcely say anything respecting them but what is painted in the blackest colours, and savours of the most perfect hatred.’ Collinson, The Religion of Protestants, p. 41; sadly, Sandy’s actual remark was not so succinct: London, British Library Lansdowne, MS 17, f. 96; Heinrich Bullinger and Rudolph Gwalther to Theodore Beza, 3 August 1567, in Robinson, The Zurich letters (2nd Series), p. 155 Criticism gained support because it tapped into a traditional anticlericalismOpposition to the practices and power of the clergy, particularly in secular matters.Opposition to the practices and power of the clergy, particularly in secularNot connected with religious matters. matters. Opposition to the practices and power of the clergy, particularly in secularNot connected with religious matters. matters. Opposition to the practices and power of the clergy, particularly in secularNot connected with religious matters. matters. Opposition to the practices and power of the clergy, particularly in secularNot connected with religious matters. matters. Opposition to the practices and power of the clergy, particularly in secularNot connected with religious matters. matters. Opposition to the practices and power of the clergy, particularly in secularNot connected with religious matters. matters. with a much wider reach than the core of puritan idealists, and because it used witty and satiricalCriticising something, particularly social or political, in a humorous way.Criticising something, particularly social or political, in a humorous way. Criticising something, particularly social or political, in a humorous way. Criticising something, particularly social or political, in a humorous way. Criticising something, particularly social or political, in a humorous way. Criticising something, particularly social or political, in a humorous way. Criticising something, particularly social or political, in a humorous way. propagandaBiased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view.Biased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view.Biased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view.Biased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view.Biased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view.Biased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view.Biased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view.Biased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view. to highlight real problems.

Collinson, The Religion of Protestants, p. 41; sadly, Sandy’s actual remark was not so succinct: London, British Library Lansdowne, MS 17, f. 96; Heinrich Bullinger and Rudolph Gwalther to Theodore Beza, 3 August 1567, in Robinson, The Zurich letters (2nd Series), p. 155 Criticism gained support because it tapped into a traditional anticlericalismOpposition to the practices and power of the clergy, particularly in secular matters.Opposition to the practices and power of the clergy, particularly in secularNot connected with religious matters. matters. Opposition to the practices and power of the clergy, particularly in secularNot connected with religious matters. matters. Opposition to the practices and power of the clergy, particularly in secularNot connected with religious matters. matters. Opposition to the practices and power of the clergy, particularly in secularNot connected with religious matters. matters. Opposition to the practices and power of the clergy, particularly in secularNot connected with religious matters. matters. Opposition to the practices and power of the clergy, particularly in secularNot connected with religious matters. matters. with a much wider reach than the core of puritan idealists, and because it used witty and satiricalCriticising something, particularly social or political, in a humorous way.Criticising something, particularly social or political, in a humorous way. Criticising something, particularly social or political, in a humorous way. Criticising something, particularly social or political, in a humorous way. Criticising something, particularly social or political, in a humorous way. Criticising something, particularly social or political, in a humorous way. Criticising something, particularly social or political, in a humorous way. propagandaBiased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view.Biased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view.Biased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view.Biased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view.Biased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view.Biased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view.Biased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view.Biased and misleading information used to promote a political cause or point of view. to highlight real problems.

Yet there was no clear continuation of presbyterianism between 1590 and 1625, although minor tremors – such as the Millenary PetitionA list of puritan requests given to James I as he made his way from Scotland to London in 1603, claiming to have 1,000 signatures.A list of puritan requests given to James I as he made his way from Scotland to London in 1603, claiming to have 1,000 signatures. A list of puritan requests given to James I as he made his way from Scotland to London in 1603, claiming to have 1,000 signatures. A list of puritan requests given to James I as he made his way from Scotland to London in 1603, claiming to have 1,000 signatures. A list of puritan requests given to James I as he made his way from Scotland to London in 1603, claiming to have 1,000 signatures. A list of puritan requests given to James I as he made his way from Scotland to London in 1603, claiming to have 1,000 signatures. A list of puritan requests given to James I as he made his way from Scotland to London in 1603, claiming to have 1,000 signatures. – occurred. Some have argued that the pamphleteers had gone too far: their vitriol was too much for the moderates who had previously been sympathetic. But in large part it is thanks to sound management, and the removal of criticism by addressing its causes. Under James, the education and quality of the clergyThe people ordained for religious duties, especially in the Christian Church. The people ordained for religious duties, especially in the Christian Church. improved, attempts were made to tackle pluralism1. Two or more types of people who have different ideas, etc, but who coexist; or support for such a state; 2. The practice of holding more than one ecclesiastical office at a time.1. Two or more types of people who have different ideas, etc, but who coexist; or support for such a state; 2. The practice of holding more than one ecclesiastical office at a time. 1. Two or more types of people who have different ideas, etc, but who coexist; or support for such a state; 2. The practice of holding more than one ecclesiastical office at a time. 1. Two or more types of people who have different ideas, etc, but who coexist; or support for such a state; 2. The practice of holding more than one ecclesiastical office at a time. 1. Two or more types of people who have different ideas, etc, but who coexist; or support for such a state; 2. The practice of holding more than one ecclesiastical office at a time. 1. Two or more types of people who have different ideas, etc, but who coexist; or support for such a state; 2. The practice of holding more than one ecclesiastical office at a time. 1. Two or more types of people who have different ideas, etc, but who coexist; or support for such a state; 2. The practice of holding more than one ecclesiastical office at a time. and non-residenceNot residing in a particular place. In religious terms, not living in the parish over which one is meant to preside.Not residing in a particular place. In religious terms, not living in the parish over which one is meant to preside. Not residing in a particular place. In religious terms, not living in the parish over which one is meant to preside. Not residing in a particular place. In religious terms, not living in the parish over which one is meant to preside. Not residing in a particular place. In religious terms, not living in the parish over which one is meant to preside. Not residing in a particular place. In religious terms, not living in the parish over which one is meant to preside. Not residing in a particular place. In religious terms, not living in the parish over which one is meant to preside. , and a light-touch approach to the enforcement of the canons1. Clerics who live a semi-monastic life, but who are also involved in the community; 2. General rules or principles by which something is judged; 3. A collection or list of sacred books accepted as genuine.1. Clerics who live a semi-monastic life, but who are also involved in the community; 2. General rules or principles by which something is judged; 3. A collection or list of sacred books accepted as genuine. 1. Clerics who live a semi-monastic life, but who are also involved in the community; 2. General rules or principles by which something is judged; 3. A collection or list of sacred books accepted as genuine. 1. Clerics who live a semi-monastic life, but who are also involved in the community; 2. General rules or principles by which something is judged; 3. A collection or list of sacred books accepted as genuine. 1. Clerics who live a semi-monastic life, but who are also involved in the community; 2. General rules or principles by which something is judged; 3. A collection or list of sacred books accepted as genuine. 1. Clerics who live a semi-monastic life, but who are also involved in the community; 2. General rules or principles by which something is judged; 3. A collection or list of sacred books accepted as genuine. 1. Clerics who live a semi-monastic life, but who are also involved in the community; 2. General rules or principles by which something is judged; 3. A collection or list of sacred books accepted as genuine. 1. Clerics who live a semi-monastic life, but who are also involved in the community; 2. General rules or principles by which something is judged; 3. A collection or list of sacred books accepted as genuine. enabled the puritan clergy to work within the church, with conformity encouraged rather than demanded. Even as late as 1629, some members of parliament were willing to grant that there were a few ‘among our Bishops such as are fit to be made examples for all Ages, who shine in virtue, and are firm for our Religion’. John Rushworth, 'Historical Collections: 1628 (part 6 of 7)', in Historical Collections of Private Passages of State: Volume 1, 1618-29 (London, 1721), pp. 627-650. British History Online <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rushworth-papers/vol1/pp627-650> [accessed 1 February 2018].

John Rushworth, 'Historical Collections: 1628 (part 6 of 7)', in Historical Collections of Private Passages of State: Volume 1, 1618-29 (London, 1721), pp. 627-650. British History Online <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rushworth-papers/vol1/pp627-650> [accessed 1 February 2018].

It was not until the ascent of anti-CalvinismA protestant system of belief derived from John Calvin, which centres on justification by faith alone (rather than good works) and predestination (the notion that God has already decided whether someone will be admitted to heaven).A protestant system of belief derived from John Calvin, which centres on justification by faith aloneOr sola fide, a Protestant doctrine that asserts God's pardon for guilty sinners is granted to and received through faith alone, excluding all 'works'. (rather than good works) and predestinationThe doctrine that God has ordained all that will happen, especially with regard to the salvation of some and not others. (the notion that God has already decided whether someone will be admitted to heaven). A protestant system of belief derived from John Calvin, which centres on justification by faith aloneOr sola fide, a Protestant doctrineThe set of beliefs upheld by a religion or political party. that asserts God's pardon for guilty sinners is granted to and received through faith alone, excluding all 'works'. (rather than good works) and predestinationThe doctrine that God has ordained all that will happen, especially with regard to the salvation of some and not others. (the notion that God has already decided whether someone will be admitted to heaven). A protestant system of belief derived from John Calvin, which centres on justification by faith aloneOr sola fide, a Protestant doctrineThe set of beliefs upheld by a religion or political party. that asserts God's pardon for guilty sinners is granted to and received through faith alone, excluding all 'works'. (rather than good works) and predestinationThe doctrine that God has ordained all that will happen, especially with regard to the salvation of some and not others. (the notion that God has already decided whether someone will be admitted to heaven). A protestant system of belief derived from John Calvin, which centres on justification by faith aloneOr sola fide, a Protestant doctrineThe set of beliefs upheld by a religion or political party. that asserts God's pardon for guilty sinners is granted to and received through faith alone, excluding all 'works'. (rather than good works) and predestinationThe doctrine that God has ordained all that will happen, especially with regard to the salvation of some and not others. (the notion that God has already decided whether someone will be admitted to heaven). A protestant system of belief derived from John Calvin, which centres on justification by faith aloneOr sola fide, a Protestant doctrineThe set of beliefs upheld by a religion or political party. that asserts God's pardon for guilty sinners is granted to and received through faith alone, excluding all 'works'. (rather than good works) and predestinationThe doctrine that God has ordained all that will happen, especially with regard to the salvation of some and not others. (the notion that God has already decided whether someone will be admitted to heaven). A protestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. system of belief derived from John Calvin, which centres on justification by faith aloneOr sola fide, a Protestant doctrineThe set of beliefs upheld by a religion or political party. that asserts God's pardon for guilty sinners is granted to and received through faith alone, excluding all 'works'. (rather than good works) and predestinationThe doctrine that God has ordained all that will happen, especially with regard to the salvation of some and not others. (the notion that God has already decided whether someone will be admitted to heaven). , provoked in part by the fear of a puritan fifth columnA group within a society or state that is working against that society or state.A group within a society or state that is working against that society or state. A group within a society or state that is working against that society or state. A group within a society or state that is working against that society or state. A group within a society or state that is working against that society or state. A group within a society or state that is working against that society or state. A group within a society or state that is working against that society or state. , that presbyterianism again became a problem. But this presbyterianism was a reflection of deeper anxieties over the religious direction of the church and state. Anti-Calvinism had developed from the concern of some within the church that reform had gone too far, from questioning Calvinist doctrines such as double predestinationThe doctrineThe set of beliefs upheld by a religion or political party. that God has ordained all that will happen, especially with regard to the salvation of some and not others. The doctrine that God has ordained all that will happen, especially with regard to the salvation of some and not others. , and from belief in piety through expression, ceremonialism, and beauty. This supposedly embattled minority, which has variously been termed ‘ArminianRelating to the doctrines of Jacobus Arminius, who rejected the Calvinist theory of predestination (which says that God has already preordained what will happen, including who will go to Heaven and Hell).Relating to the doctrines of Jacobus Arminius, who rejected the Calvinist theory of predestination (which says that God has already preordained what will happen, including who will go to Heaven and Hell). Relating to the doctrines of Jacobus Arminius, who rejected the Calvinist theory of predestination (which says that God has already preordained what will happen, including who will go to Heaven and Hell). Relating to the doctrines of Jacobus Arminius, who rejected the Calvinist theory of predestination (which says that God has already preordained what will happen, including who will go to Heaven and Hell). Relating to the doctrines of Jacobus Arminius, who rejected the Calvinist theory of predestination (which says that God has already preordained what will happen, including who will go to Heaven and Hell). Relating to the doctrines of Jacobus Arminius, who rejected the Calvinist theory of predestination (which says that God has already preordained what will happen, including who will go to Heaven and Hell). Relating to the doctrines of Jacobus Arminius, who rejected the Calvinist theory of predestination (which says that God has already preordained what will happen, including who will go to Heaven and Hell). Relating to the doctrines of Jacobus Arminius, who rejected the Calvinist theory of predestination (which says that God has already preordained what will happen, including who will go to Heaven and Hell). ’ and ‘LaudianReforms introduced to the mainly Calvinist Church of England by William Laud in the reign of Charles I, which pushed for the rejection of predestination and the belief that all men could achieve salvation.Reforms introduced to the mainly Calvinist Church of England by William Laud in the reign of Charles I, which pushed for the rejection of predestination and the belief that all men could achieve salvation. Reforms introduced to the mainly Calvinist Church of England by William Laud in the reign of Charles I, which pushed for the rejection of predestination and the belief that all men could achieve salvation. Reforms introduced to the mainly Calvinist Church of England by William Laud in the reign of Charles I, which pushed for the rejection of predestination and the belief that all men could achieve salvation. Reforms introduced to the mainly Calvinist Church of England by William Laud in the reign of Charles I, which pushed for the rejection of predestination and the belief that all men could achieve salvation. Reforms introduced to the mainly Calvinist Church of England by William Laud in the reign of Charles I, which pushed for the rejection of predestination and the belief that all men could achieve salvation. Reforms introduced to the mainly Calvinist Church of England by William Laud in the reign of Charles I, which pushed for the rejection of predestination and the belief that all men could achieve salvation. Reforms introduced to the mainly Calvinist Church of England by William Laud in the reign of Charles I, which pushed for the rejection of predestination and the belief that all men could achieve salvation. ’, carried their persecution complex forward and into power under Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud and Charles I. As the political climate changed in the 1630s, reluctantly-conforming Calvinist clergy were removed from their positions and turned into opponents. Laud’s dogged insistence ‘that the calling of bishops is jure divinoBy divine right: sanctioned by God.By divine right: sanctioned by God. By divine right: sanctioned by God. By divine right: sanctioned by God. By divine right: sanctioned by God. By divine right: sanctioned by God. By divine right: sanctioned by God. , by divine right’, and that ‘in all ages, in all places, the Church of Christ was governed by bishops, and lay elders never heard of till Calvin’s new-fangled device at Geneva’, was hardly designed to calm his opponents. Rushworth, 'Laud's speech at the Censure of Burton, Bastwick and Prynne, 1637', in Historical Collections Vol. 3, pp. 116-133. British History Online <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rushworth-papers/vol3/pp116-133> [accessed 29 January 2018]. In fact, it did the opposite: those whom he was attacking in this instance, William Prynne, John Bastwick, and Henry Burton, had originally accepted the Elizabethan settlement, but had become more and more worried by the direction the church was taking under Charles and Laud. Since the founding of the Church of England, puritanism as a potential threat had been weakened by divisions on everything from doctrine to forms of worship and levels of conformity. Now, it was united in its fight against the enemy within.

Rushworth, 'Laud's speech at the Censure of Burton, Bastwick and Prynne, 1637', in Historical Collections Vol. 3, pp. 116-133. British History Online <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rushworth-papers/vol3/pp116-133> [accessed 29 January 2018]. In fact, it did the opposite: those whom he was attacking in this instance, William Prynne, John Bastwick, and Henry Burton, had originally accepted the Elizabethan settlement, but had become more and more worried by the direction the church was taking under Charles and Laud. Since the founding of the Church of England, puritanism as a potential threat had been weakened by divisions on everything from doctrine to forms of worship and levels of conformity. Now, it was united in its fight against the enemy within.

The role of the monarch

The episcopacy was only one strand in the governance of the Church of England; the other was its supreme governor, the monarch. The church was therefore intricately linked with the state, and both were based on notions of hierarchy and obedience. To question the divine right of one, was to question the divine right of the other: as James, who had spent his time as Scottish king trying to restore the episcopacy, blurted: ‘no bishop, no king’. William Barlow’s account of the Hampton Court Conference, Sum and Substance of the Conference,cited in J.R. Tanner, Constitutional Documents of the Reign of James I, AD 1603-1625 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1952), p. 63. No wonder, then, that Elizabeth, James, and Charles were all distrustful of puritanism. Elizabeth noted ‘the fanatical humour of ... the PuritanDescribing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism. Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism. Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism. Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism. Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism. Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism. Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism. ’, and James thought it promoted ‘unprofitable, unsound, seditious and dangerous doctrines, to the scandalAn event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action.An event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action. An event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action. An event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action. An event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action. An event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action. An event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action. An event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action. of the Church and disquiet of the state and present government’.

William Barlow’s account of the Hampton Court Conference, Sum and Substance of the Conference,cited in J.R. Tanner, Constitutional Documents of the Reign of James I, AD 1603-1625 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1952), p. 63. No wonder, then, that Elizabeth, James, and Charles were all distrustful of puritanism. Elizabeth noted ‘the fanatical humour of ... the PuritanDescribing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism. Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism. Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism. Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism. Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism. Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism. Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism. ’, and James thought it promoted ‘unprofitable, unsound, seditious and dangerous doctrines, to the scandalAn event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action.An event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action. An event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action. An event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action. An event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action. An event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action. An event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action. An event or action that causes public outrage, or the outrage caused by that event or action. of the Church and disquiet of the state and present government’. Christopher Hatton’s closing speech to parliament, 1589, cited in J. E. Neale, Elizabeth and Her Parliaments 1584-1601 Vol. II, London: Cape (1957), p. 238;‘Directions to preachers, 1622’ in Rushworth, 'Historical Collections: 1622', in Historical Collections, Vol. 1, pp. 62-78. British History Online <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rushworth-papers/vol1/pp62-78 > [accessed 30 January 2018]. Charles, in a proclamationA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importance parliament had originally hoped would be anti-Arminian in nature, declared ‘His utter dislike to all those, who … adventure to stirre or move any new Opinions … differing from the sound and Orthodoxall grounds of the true Religion, sincerely professed, and happily established in the Church of England’.

Christopher Hatton’s closing speech to parliament, 1589, cited in J. E. Neale, Elizabeth and Her Parliaments 1584-1601 Vol. II, London: Cape (1957), p. 238;‘Directions to preachers, 1622’ in Rushworth, 'Historical Collections: 1622', in Historical Collections, Vol. 1, pp. 62-78. British History Online <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rushworth-papers/vol1/pp62-78 > [accessed 30 January 2018]. Charles, in a proclamationA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importance parliament had originally hoped would be anti-Arminian in nature, declared ‘His utter dislike to all those, who … adventure to stirre or move any new Opinions … differing from the sound and Orthodoxall grounds of the true Religion, sincerely professed, and happily established in the Church of England’. 'A ProclamationA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importance for the establishing of the Peace and Quiet of the Church of England', 14 June 1626, in James F. Larkin (ed.), Stuart royal proclamations. Vol. 2, Royal proclamations of King Charles I, 1625-1646 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1983), pp. 91-3. His true intent was clear when it was shortly afterwards used to prevent Calvinist debates at Cambridge University.

'A ProclamationA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importance for the establishing of the Peace and Quiet of the Church of England', 14 June 1626, in James F. Larkin (ed.), Stuart royal proclamations. Vol. 2, Royal proclamations of King Charles I, 1625-1646 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1983), pp. 91-3. His true intent was clear when it was shortly afterwards used to prevent Calvinist debates at Cambridge University.

In a world where uniformity of religion expressed unity of state, doctrinal disputes, often preached or published in pamphlets, threatened dissension. The extra-legal ‘voluntary religion’ – the preaching, psalm-singing, fasting, household prayers, and sermon repetition favoured by puritans – theoretically opened the way for schismA split within a group caused by strongly held beliefs or opinions.A split within a group caused by strongly held beliefs or opinions. A split within a group caused by strongly held beliefs or opinions. A split within a group caused by strongly held beliefs or opinions. A split within a group caused by strongly held beliefs or opinions. A split within a group caused by strongly held beliefs or opinions. , and for the ill-informed masses to question government. Disharmony in religion could also provoke disharmony in the community. Richard Bancroft complained about the self-satisfied elect, who ‘condemn all others for papists’. Cited in David Cressy and Lori Anne Ferrell (ed.s), Religion and society in early modern England: a sourcebook, 2nd ed., (London: Routledge, 2005), p. 248. What’s more, each monarch – Elizabeth, James, and Charles – was fiercely protective of their prerogativeA right or privilege exclusive to a particular person or group.A right or privilege exclusive to a particular person or group. A right or privilege exclusive to a particular person or group. A right or privilege exclusive to a particular person or group. A right or privilege exclusive to a particular person or group. A right or privilege exclusive to a particular person or group. A right or privilege exclusive to a particular person or group. A right or privilege exclusive to a particular person or group. . When Archbishop Grindal wrote to Elizabeth that he would ‘choose rather to offend your earthly majesty, than to offend the heavenly majesty of God’, he touched a nerve.

Cited in David Cressy and Lori Anne Ferrell (ed.s), Religion and society in early modern England: a sourcebook, 2nd ed., (London: Routledge, 2005), p. 248. What’s more, each monarch – Elizabeth, James, and Charles – was fiercely protective of their prerogativeA right or privilege exclusive to a particular person or group.A right or privilege exclusive to a particular person or group. A right or privilege exclusive to a particular person or group. A right or privilege exclusive to a particular person or group. A right or privilege exclusive to a particular person or group. A right or privilege exclusive to a particular person or group. A right or privilege exclusive to a particular person or group. A right or privilege exclusive to a particular person or group. . When Archbishop Grindal wrote to Elizabeth that he would ‘choose rather to offend your earthly majesty, than to offend the heavenly majesty of God’, he touched a nerve. Ibid., pp. 215-6. Elizabeth ‘was not prepared to tolerate either a pope of Rome or a pope who had learnt his business in Geneva.’

Ibid., pp. 215-6. Elizabeth ‘was not prepared to tolerate either a pope of Rome or a pope who had learnt his business in Geneva.’ Patrick McGrath, Papists and Puritans under Elizabeth I (London: Blandford, 1967), p. 10. The Thirty-Nine ArticlesDrawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them.Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. , the prohibition on prophesyingsReligious meetings and exercises used to discuss Biblical passages and sermons, which were often considered to threaten the officially-sanctioned understanding the Bible.Religious meetings and exercises used to discuss Biblical passages and sermons, which were often considered to threaten the officially-sanctioned understanding the Bible. Religious meetings and exercises used to discuss Biblical passages and sermons, which were often considered to threaten the officially-sanctioned understanding the Bible. Religious meetings and exercises used to discuss Biblical passages and sermons, which were often considered to threaten the officially-sanctioned understanding the Bible. Religious meetings and exercises used to discuss Biblical passages and sermons, which were often considered to threaten the officially-sanctioned understanding the Bible. Religious meetings and exercises used to discuss Biblical passages and sermons, which were often considered to threaten the officially-sanctioned understanding the Bible. , and the Act to Retain the Queen’s Subjects in Obedience all sought to limit the perceived threat of puritanism. James considered opposition to the match between Charles and the Spanish InfantaDaughter of the ruling monarch of Spain or Portugal.Daughter of the ruling monarch of Spain or Portugal. Daughter of the ruling monarch of Spain or Portugal. Daughter of the ruling monarch of Spain or Portugal. Daughter of the ruling monarch of Spain or Portugal. Daughter of the ruling monarch of Spain or Portugal. , and thus to his desire to be Rex Pacificus'King of peace'.'King of peace'. 'King of peace'. 'King of peace'. 'King of peace'. 'King of peace'. , as a puritan infringement on his prerogative. Foreshadowing his son, he turned to the anti-Calvinists for support, and released his Directions to Preachers banning puritan ‘ignorant meddling with civil matters’, and preaching ‘in any popular auditory the deep points of predestination, election, reprobation, or of the universality, efficacy, resistibility or irresistibility, of God’s grace’.

Patrick McGrath, Papists and Puritans under Elizabeth I (London: Blandford, 1967), p. 10. The Thirty-Nine ArticlesDrawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them.Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. , the prohibition on prophesyingsReligious meetings and exercises used to discuss Biblical passages and sermons, which were often considered to threaten the officially-sanctioned understanding the Bible.Religious meetings and exercises used to discuss Biblical passages and sermons, which were often considered to threaten the officially-sanctioned understanding the Bible. Religious meetings and exercises used to discuss Biblical passages and sermons, which were often considered to threaten the officially-sanctioned understanding the Bible. Religious meetings and exercises used to discuss Biblical passages and sermons, which were often considered to threaten the officially-sanctioned understanding the Bible. Religious meetings and exercises used to discuss Biblical passages and sermons, which were often considered to threaten the officially-sanctioned understanding the Bible. Religious meetings and exercises used to discuss Biblical passages and sermons, which were often considered to threaten the officially-sanctioned understanding the Bible. , and the Act to Retain the Queen’s Subjects in Obedience all sought to limit the perceived threat of puritanism. James considered opposition to the match between Charles and the Spanish InfantaDaughter of the ruling monarch of Spain or Portugal.Daughter of the ruling monarch of Spain or Portugal. Daughter of the ruling monarch of Spain or Portugal. Daughter of the ruling monarch of Spain or Portugal. Daughter of the ruling monarch of Spain or Portugal. Daughter of the ruling monarch of Spain or Portugal. , and thus to his desire to be Rex Pacificus'King of peace'.'King of peace'. 'King of peace'. 'King of peace'. 'King of peace'. 'King of peace'. , as a puritan infringement on his prerogative. Foreshadowing his son, he turned to the anti-Calvinists for support, and released his Directions to Preachers banning puritan ‘ignorant meddling with civil matters’, and preaching ‘in any popular auditory the deep points of predestination, election, reprobation, or of the universality, efficacy, resistibility or irresistibility, of God’s grace’. Abbot’s letter regarding the Directions to Preachers, 1622, cited in Cressy and Ferrell, Religion and society in early modern England, pp. 321-2; ‘Directions to preachers, 1622’ in Rushworth, 'Historical Collections: 1622', in Historical Collections, pp. 62-78. British History Online <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rushworth-papers/vol1/pp62-78> [accessed 30 January 2018]. Even before this, his promotion of sports on the Sabbath and the development of the 1604 canons, to which he ordered subscription, ensured that the extremes of Calvinism were kept in check.

Abbot’s letter regarding the Directions to Preachers, 1622, cited in Cressy and Ferrell, Religion and society in early modern England, pp. 321-2; ‘Directions to preachers, 1622’ in Rushworth, 'Historical Collections: 1622', in Historical Collections, pp. 62-78. British History Online <http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rushworth-papers/vol1/pp62-78> [accessed 30 January 2018]. Even before this, his promotion of sports on the Sabbath and the development of the 1604 canons, to which he ordered subscription, ensured that the extremes of Calvinism were kept in check.

Harsh though these measures might be – James was accused of depriving 300 pastors for their refusal to subscribe to the canons – their bark was worse than their bite. The show of conformity, rather than its essence, is what mattered to James and his predecessorA person who held a job or office before the current holder.A person who held a job or office before the current holder.A person who held a job or office before the current holder.A person who held a job or office before the current holder.A person who held a job or office before the current holder.A person who held a job or office before the current holder.A person who held a job or office before the current holder.A person who held a job or office before the current holder.. Elizabeth never formally approved Matthew Parker’s Advertisements of 1565, Designed to address the Vestiarian Controversy and enforce the wearing of the surplice. and the Thirty-Nine articlesDrawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. allowed room for a wide interpretation. James listened and responded to puritan complaints at the Hampton Court Conference, including commissioning a new translation of the Bible, altering some of the liturgical language, and attempting to improve the quality of the ministry. Nor did he enforce the canons in a sustained way: the 300 deprivations were closer to 80, and most were in the years immediately following their introduction. Both monarchs could therefore be seen as godly princes, allowing potential critics to view them in a favourable light. It gave moderate puritans the chance to stay within the church, rather than forcing them to work outside it, and divided what could otherwise have been a much more united – and therefore dangerous – puritan front.

Designed to address the Vestiarian Controversy and enforce the wearing of the surplice. and the Thirty-Nine articlesDrawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. Drawn up by convocation in 1563, the Articles listed the fundamental basis of Anglican doctrine. They gave a distinctive middle way between the more extreme Calvinist doctrines and those of the Catholic church, and in 1571 parliament agreed that all clergymen should subscribe to them. allowed room for a wide interpretation. James listened and responded to puritan complaints at the Hampton Court Conference, including commissioning a new translation of the Bible, altering some of the liturgical language, and attempting to improve the quality of the ministry. Nor did he enforce the canons in a sustained way: the 300 deprivations were closer to 80, and most were in the years immediately following their introduction. Both monarchs could therefore be seen as godly princes, allowing potential critics to view them in a favourable light. It gave moderate puritans the chance to stay within the church, rather than forcing them to work outside it, and divided what could otherwise have been a much more united – and therefore dangerous – puritan front.

Charles, it could be argued, did not go much further than his father in promoting the agreed doctrine of the church: his Book of SportsInstructions for allowable Sunday amusements, designed to curb puritan disapproval of Sunday pass times that weren't related to Bible study. Originally issued by James I, but allowed to slide due to puritan opposition, Charles I reissued it in 1633 and ordered the clergy to read it from their pulpits.Instructions for allowable Sunday amusements, designed to curb puritan disapproval of Sunday pass times that weren't related to Bible study. Originally issued by James I, but allowed to slide due to puritan opposition, Charles I reissued it in 1633 and ordered the clergy to read it from their…Instructions for allowable Sunday amusements, designed to curb puritan disapproval of Sunday pass times that weren't related to Bible study. Originally issued by James I, but allowed to slide due to puritan opposition, Charles I reissued it in 1633 and ordered the clergy to read it from their…Instructions for allowable Sunday amusements, designed to curb puritan disapproval of Sunday pass times that weren't related to Bible study. Originally issued by James I, but allowed to slide due to puritan opposition, Charles I reissued it in 1633 and ordered the clergy to read it from their…Instructions for allowable Sunday amusements, designed to curb puritan disapproval of Sunday pass times that weren't related to Bible study. Originally issued by James I, but allowed to slide due to puritan opposition, Charles I reissued it in 1633 and ordered the clergy to read it from their…Instructions for allowable Sunday amusements, designed to curb puritan disapproval of Sunday pass times that weren't related to Bible study. Originally issued by James I, but allowed to slide due to puritan opposition, Charles I reissued it in 1633 and ordered the clergy to read it from their…, for example, was a reiteration of James’ 1618 Declaration of Sports. Like his father, he too saw the danger to the people, church, and state in SabbatarianismThe belief in the strict observance of the Sabbath as a purely religious day.The belief in the strict observance of the Sabbath as a purely religious day. The belief in the strict observance of the Sabbath as a purely religious day. The belief in the strict observance of the Sabbath as a purely religious day. The belief in the strict observance of the Sabbath as a purely religious day. The belief in the strict observance of the Sabbath as a purely religious day. . But, unlike his father, he enforced the 1604 canons to the letter, as he likewise did with the Thirty-Nine Articles, demanding subscription to them ‘in the literal and grammatical sense.’ Henry Gee and William John Hardy, Documents Illustrative of English Church History (London: Macmillan, 1896), pp. 518-20. Encouraged, as it was believed, by his Catholic wife and the anti-Calvinists at court, he emphasised ritual and show. But to many, the vestments and practices he insisted upon – such as the position of the communion table – felt like an encroachment of Catholic values into the English church. The puritan faith in the faith of their king was shaken.

Henry Gee and William John Hardy, Documents Illustrative of English Church History (London: Macmillan, 1896), pp. 518-20. Encouraged, as it was believed, by his Catholic wife and the anti-Calvinists at court, he emphasised ritual and show. But to many, the vestments and practices he insisted upon – such as the position of the communion table – felt like an encroachment of Catholic values into the English church. The puritan faith in the faith of their king was shaken.

Tyacke overstated the Calvinism of the English church. Elizabeth and James had succeeded in creating the appearance of unity, but it was the unity of a middle way, a compromise between preaching and ceremonial, double predestination and the mercy of God. Since at least the 1590s, anti-Calvinism had existed within the church, but tensions between them had been well managed. Both sides were elevated to positions of power and had supporters within the privy councilA monarch's private advisers.A monarch's private advisers.A monarch's private advisers.A monarch's private advisers.A monarch's private advisers.A monarch's private advisers.A monarch's private advisers.A monarch's private advisers., ensuring balance between the parties. But from 1625, anti-Calvinists dominated episcopal appointments and promotions, holding four of the five key sees by 1633, and all of the clerical positions at court. ‘Arminianism’ wasn’t an innovation; it could even be argued that James favoured it towards the end of his life. But under Charles anti-Calvinism triumphed, and when those on the inside suddenly found themselves on the outside, puritanism became a threat to the church. The abrupt change in the actual, rather than theoretical, practice of the church and its governance made opponents of even moderate Calvinists. Historians such as Roger Lockyer have argued that Charles’s anti-Calvinism was not as extreme as commonly believed and instead point to Laud as ‘the greatest calamityDisasterDisasterDisasterDisasterDisasterDisasterDisaster ever visited upon the English Church’. Collinson, The Religion of Protestants, pp. 90-1. But it was Charles, stubborn to the point of death, who oversaw the direction of the church and the appointment of favourites, and he who must take ultimate responsibility.