Monarchs Behaving Badly: James I and the Visit of Christian IV of Denmark

James I of England (and VI of Scotland) has not always had a good reputation. Known as ‘the wisest fool in Christendome’, he was considered slovenly, his tongue was reportedly too big for his mouth, making him both a messy eater and occasionally difficult to understand (although he did like the sound of his own voice), and he took too personal an interest in people’s private affairs – such as when he inquired in intimate detail about his daughter’s wedding night. Anthony Weldon, The Court and Character of James I (1650, repr. 1817), p. 58. It is hardly a surprise, then, that one historian said of him that ‘Few kings have been so fitted by nature to call forth an Opposition’.

Anthony Weldon, The Court and Character of James I (1650, repr. 1817), p. 58. It is hardly a surprise, then, that one historian said of him that ‘Few kings have been so fitted by nature to call forth an Opposition’. Wallace Notestein, The Winning of the Initiative by the House of Commons, (London: British Academy and Oxford University Press, 1924), p. 33.

Wallace Notestein, The Winning of the Initiative by the House of Commons, (London: British Academy and Oxford University Press, 1924), p. 33.

Since Wallace Notestein made this damning remark in 1924, historians have made a valiant effort to redeem the king’s character, but he didn’t always make their job easy. One such lapse in anything approaching ‘correct’ kingly behaviour was when his brother-in-law, King Christian IV of Denmark, paid a state visit in July 1606.

Christian, just 29 when he first came to England, had a name for hard-drinking – in later life, he had to be carried away from the table after drinking 35 toasts – and this was put to the test throughout his stay. As Sir John Harington, godson to the late Queen Elizabeth and witness to much of the celebrations, reported, ‘… from the day he did come untill [sic] this hour I have been well nigh overwhelmed with carousal and sports of all kinds.’ Each day, from the moment of rising, there were women and wine aplenty. Even those of the courtly circle who always refused drink ‘now follow the fashion, and wallow in beastly delights. The ladies abandon their sobriety, and are seen to roll about in intoxication.’ Harington to Secretary Barlow, John Harington, Nugae Antiquae: Being a Miscellaneous Collection of Original Papers, 2 vols (London, 1804), vol. I, pp. 348-9.

Harington to Secretary Barlow, John Harington, Nugae Antiquae: Being a Miscellaneous Collection of Original Papers, 2 vols (London, 1804), vol. I, pp. 348-9.

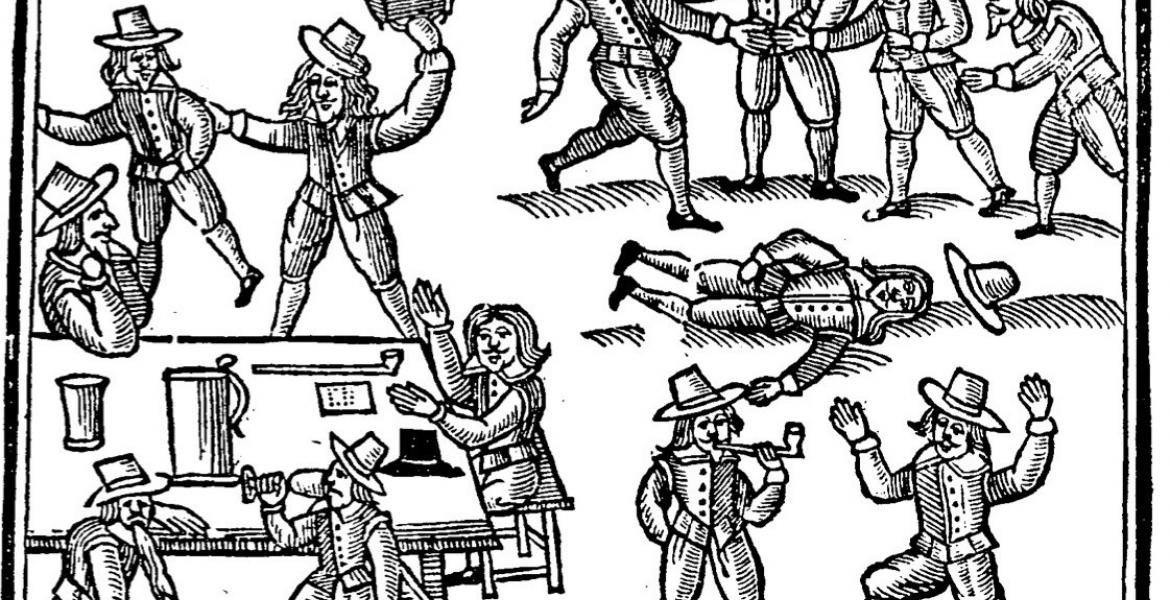

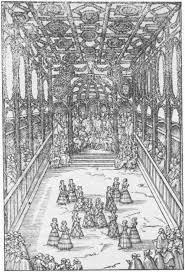

This, however, was just a warm-up. The fashionable court entertainment of the early Stuarts was the court masque. In this craze, which had originated in Italy but was sweeping through Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, courtiers would dance, sing, and perform allegorical plays often written by the greatest playwrights of the day – Ben Jonson was a particularly prolific writer. They were supported by elaborate sets, designed by the likes of the great architect Inigo Jones, and accomplished musicians. The politician and philosopher Sir Francis Bacon provides a glimpse of these opulent affairs in one of his Essays: 'Let the scenes abound with light, specially coloured and varied; ... Let the songs be loud and cheerful, and not chirpings or pulings. Let the music likewise be sharp and loud, and well placed. Let the suits of the masquers be graceful, and such as become the person when the vizards are off'. Francis Bacon, 'Of Masques and Triumphs', in The Major Works, ed. by Brian Vickers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 416-7. In theory, then, these masques were elegant and sumptuous displays, designed to present the court at its best.

Francis Bacon, 'Of Masques and Triumphs', in The Major Works, ed. by Brian Vickers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 416-7. In theory, then, these masques were elegant and sumptuous displays, designed to present the court at its best.

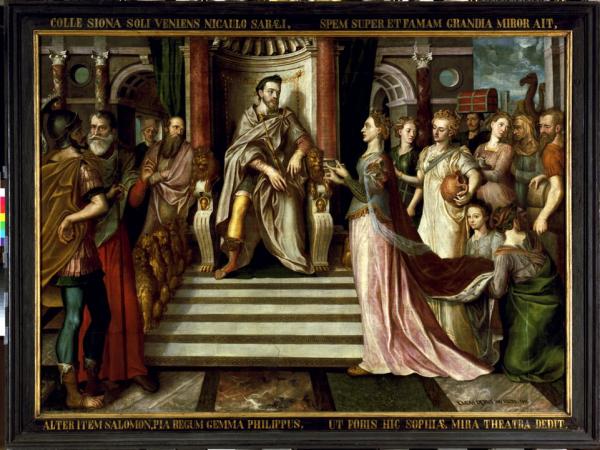

But then there was the performance of Solomon and the queen of Sheba, specially arranged by James’s ‘Little Beagle’, the Lord Privy Seal and smooth political operator Robert Cecil, earl of Salisbury, at Theobalds in Hertfordshire. By the time the performance commenced, everybody was already in their cups, having enjoyed a lavish feast accompanied by excessive drinking. What happened next was more worthy of a farce than an example of refinement: ‘The Lady who did play the Queens part, did carry most precious gifts to both their Majesties; but, forgetting the steppes arising to the canopy, overset her caskets into his Danish Majesties lap, and fell at his feet, tho’ I rather think it was in his face.’ Servants rushed to flap around the Danish king, who was covered in all sorts of sweet treats, ‘wine, cream, jelly, beverage, cakes, spices, and other good matters’, trying their best to remove the worst of the damage with napkins and cloths. To put the lady’s mind at peace, Christian insisted on getting up to dance with the unfortunate courtier, ‘but he fell down and humbled himself before her, and was carried to an inner chamber and laid on a bed of state; which was not a little defiled with the presents of the Queen which had been bestowed on his garments’. Ibid., p. 350.

Ibid., p. 350.

Not to be put off by the unconscious guest of honour, ‘The entertainment and show went forward, and most of the presenters went backward, or fell down; wine did so occupy their upper chambers.’ Next to perform were the three Biblical virtues of Faith, Hope and Charity, represented by three ladies richly dressed. Hope was the first to attempt to speak, ‘but wine renderd her endeavours so feeble that she withdrew, and hoped the King would excuse her brevity. Faith was then all alone, for I am certain she was not joyned with good works, and left the court in a staggering condition.’ Harington here is punning on sola fide, or ‘faith alone’, the protestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation.Someone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation.Someone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. Reformation. notion that faith alone – rather than good works – is necessary for obtaining God’s forgiveness. Charity put on a better show, presenting her gifts, uttering fine words, and leaving gracefully. ‘She then returnd to Hope and Faith, who were both sick and spewing in the lower hall.’

Harington here is punning on sola fide, or ‘faith alone’, the protestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation.Someone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation.Someone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the ProtestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. Reformation. notion that faith alone – rather than good works – is necessary for obtaining God’s forgiveness. Charity put on a better show, presenting her gifts, uttering fine words, and leaving gracefully. ‘She then returnd to Hope and Faith, who were both sick and spewing in the lower hall.’ Ibid., pp. 350-1.

Ibid., pp. 350-1.

The parade didn’t end there. Next came a lady dressed as the Roman goddess Victory, complete with armour, wings and a wreath, who presented a sword to the remaining king. Apparently, James – who was never particularly inclined to war – was unwilling to accept the gift, and instead placed it to one side. So Victory pressed the gift again, ‘and, by a strange medley of versification, did endeavour to make suit to the King. But Victory did not tryumph long; for, after much lamentable utterance, she was led away like a silly captive, and laid to sleep in the outer steps of the anti-chamber.’ Ibid., p. 351.

Ibid., p. 351.

More goddesses followed, including Peace, shoving and pushing to make her way to the king. When she was hindered by other members of party, she turned on them ‘and, much contrary to her semblance, most rudely made war with her olive branch, and laid on the pates of those who did oppose her coming.’  Ibid., p. 351.

Ibid., p. 351.

There are those who question Harington’s account of the masque, suggesting it was the bitter rhetoricThe art of effective or persuasive speaking or writing.The art of effective or persuasive speaking or writing.The art of effective or persuasive speaking or writing. of someone who had fallen out of favour and who was instead trying his luck with James’s puritanDescribing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of Catholicism.Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of CatholicismThe faith and practices of the Roman Catholic Church.. Describing a person, group, or ideal, that believed in the need to continue reform of the Church of England and rid it of remaining traces of CatholicismThe faith and practices of the Roman Catholic Church. . -leaning son, Prince Henry. There are few other accounts of the masque, and those that do exist don’t mention the revelries in any detail. See, for example, Clare McManus, ‘When Is a Woman Not a Woman? Or, Jacobean Fantasies of Female Performance (1606–1611)’, Modern Philology 105 (2008), pp. 437-474. However, as well as Harington asking his correspondent to keep the details secret – which might in reality be the early modern equivalent of a pink neon flashing sign – there are reports of raucousLoud, excitable, uncontrolled, often not in a pleasant way.Loud, excitable, uncontrolled, often not in a pleasant way. Loud, excitable, uncontrolled, often not in a pleasant way. behaviour at other points during King Christian’s visit to England.

See, for example, Clare McManus, ‘When Is a Woman Not a Woman? Or, Jacobean Fantasies of Female Performance (1606–1611)’, Modern Philology 105 (2008), pp. 437-474. However, as well as Harington asking his correspondent to keep the details secret – which might in reality be the early modern equivalent of a pink neon flashing sign – there are reports of raucousLoud, excitable, uncontrolled, often not in a pleasant way.Loud, excitable, uncontrolled, often not in a pleasant way. Loud, excitable, uncontrolled, often not in a pleasant way. behaviour at other points during King Christian’s visit to England.

One such occasion was the party thrown at Danish king’s departure, on 11 August 1606. The final farewell took place aboard the king’s ships, where ‘what was wanting in meat and other ceremony was helped out in drink and gunshot’. The company drank 20 healths – or toasts – and for every one, the ships fired a salute, to the point that James became irritated by the smell of powder. But before long, ‘good store of healths made him so hearty that he bid them at last shoot and spare not and very resolutely commanded the trumpets to sound to the point of war.’ Dudley Carleton to John Chamberlain, 20 August 1606, in Dudley Carleton to John Chamberlain, 1603-1624, ed. by Maurice Lee (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1972), pp. 87-8.

Dudley Carleton to John Chamberlain, 20 August 1606, in Dudley Carleton to John Chamberlain, 1603-1624, ed. by Maurice Lee (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1972), pp. 87-8.

The guests became so tipsy that accidents were bound to happen, and not long afterwards two of the courtiers in attendance, the Kentish MP Sir John Leveson and the MP for Winchelsea, Sir Hugh Beeston, gave the entire company a scare. Drunkenly standing on the edge of a small boat, they toppled it and fell into the deep water, ‘to search, belike, whether there was no gunpowder treason practising against the two kings.’ Those remaining above the water immediately swung into action in a rescue attempt. ‘Sir John Lucen was first ketched up and being pulled by the breeches, which were but taffeta and old linings, had them clean torn off, and the first things which appeared … was his cue and his cullions, which as the Danes confessed could be no discredit to Kent or Christendom.’  Ibid., p. 88.

Ibid., p. 88.

Leveson was safe – and semi-naked – but all the while Beeston was nowhere to be seen. Panic ensued, as it would in a time when few clothes were designed for buoyancy, few people could swim, and even fewer would consider venturing into the dirty waters around London. A boat was hastily let down into the water to search for him, but came back empty handed. As hope disappeared, the mood became sombre. Then one of the boatmen who had been aiding the search spotted a single hand holding onto a boat. Beeston, enjoying the uproar he was causing, ‘all this while had his head under the water and, like a crafty knave … held his breath’. The story spread quickly through the court and their acquaintance, and Beeston’s fame grew. ‘The good knight by this accident hath changed his name and is called about this town Sir Water Beeston’. Ibid.

Ibid.

By these accounts, the whole visit of Christian IV was one long party, filled with debauchery, merrymaking and drunken antics. No-one was seriously hurt and it provided hours of gossip at the time, and fun reading for historians since. The pantomime at Theobalds did little to damage Cecil, who continued to play an important role in government, although it did possibly cost him his beloved house: James exchanged nearby Hatfield House for it the following year, and Hatfield has remained in the Salisbury family since.

However, this jolly visit perhaps wounded the reputation of the king and his court more than they could see. James was a costly monarchA king, queen, or emperorA king, queen, or emperorA king, queen, or emperor to have on the throne, and his approach to government, while not as bad as historians once assumed, was not ‘what was done’. His speeches, the way he presented the monarchyThe king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head.The king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head.The king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head., and the way he distanced himself from his subjects could be irritating and, to some, could seem downright dangerous. As James’s reign progressed and as the memories of the bad final years under Elizabeth faded, people couldn’t help but unfavourably compare this Stuart monarch to their Gloriana. Perhaps, then, the final conclusion of Christian IV’s visit to England should be left to the words of Elizabeth’s embittered godson:

I ne’er did see such lack of good order, discretion, and sobriety, as I have now done. I have passed much time in seeing the royal sports of hunting and hawking, where the manners were such as made me devise the beasts were pursuing the sober creation, and not man in quest of exercise or food. I will now, in good sooth, declare to you, who will not blab, that the gunpowder fright is got out of all our heads, and we are going on, hereabouts, as if the devil was contriving every man shoud blow up himself, by wild riot, excess, and devastation of time and temperance. The great ladies do go well-masked, and indeed it be the only show of their modesty, to conceal their countenance; but, alack, they meet with such countenance to uphold their strange doings, that I marvel not at ought that happens. … I do often say (but not aloud) that the Danes have again conquered the Britains [sic], for I see no man, or woman either, that can now command himself or herself.’

Harington to Secretary Barlow, Harington, Nugae Antiquae, vol. I, pp. 352-3.

- Log in to post comments