The Easter Rising, 1916

Key facts about the Easter Rising

- The Easter Rising started on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916 and ended when the rebels surrendered on Saturday 29 April 2016.

- It intended to break Ireland free from British rule

- It was hampered by confusion over orders and a lack of men and weapons

- Many are unsure whether it could ever have been successful

- The leaders of the Rising, and several others were executed after surrendering

- The way the British handled the Rising led to the foundation of the Irish state.

People you need to know

- Herbert Asquith - British Liberal prime minister from 1908 until 1916.

- Roger Casement - former British diplomatA person appointed by a state to conduct diplomacy with one or more other states or organisations.A person appointed by a state to conduct diplomacy with one or more other states or organisations. and humanitarianSomeone or something concerned with human welfare.Someone or something concerned with human welfare. who sought German aid for the Easter Rising.

- James Connolly - socialist, republicanSomeone who believes power should belong to the people; someone who doesn't support a monarchy.Someone who believes power should belong to the people; someone who doesn't support a monarchyThe king/queen and royal family of a country, or a form of government with a king/queen at the head.. and co-founder of the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), vice-president of the Provisional Government and commandant-general of the Dublin division.

- Sean Conolly - an ICA officer and actor.

- Sean MacDermott - or Seán Mac Diarmada, was one of the leaders of the Rising and a signatory of the ProclamationA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importanceA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importance of the Irish Republic.

- Sean McLoughlin - an 18-year-old FiannaA nationalist Irish scout movement, based on the Celtic semi-independent warrior bands of Irish and Scottish mythology.A nationalist Irish scout movement, based on the Celtic semi-independent warrior bands of Irish and Scottish mythology. scout

- Eoin MacNeill - chief of staff of the Irish Volunteers and later a member of the government of the revolutionary Irish Republic, and the Irish Free State.

- General Sir John Maxwell - British army officer.

- The O'Rahilly - Irish republican and nationalist and founding member of the Irish Volunteers.

- Patrick Pearse - one of the leaders of the Rising and president of the Provisional Government.

- Joseph Plunkett - one of the leaders of the Rising and a signatory of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic.

- John Redmond - supporter of Home Rule and leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party.

- Eamonn de Valera - one of the leaders of the Easter Rising and later president of Ireland.

Background

The political situation in Ireland has been tricky for a long time. In 1167, one of the many kings of Ireland, Diarmait Mac Murchada, was usurpedTo have taken a (person's) position of power or importance illegally or by force.To have taken a (person's) position of power or importance illegally or by force. and in an attempt to regain his kingdom, he involved the English king, Henry II, in his fight. Henry awarded his youngest son John the 'Lordship of Ireland' as a result and when John unexpectedly became king, the Lordship fell under direct control of the kings of England. The power of the English in Ireland did eventually fade and so it stayed until Henry VIII decided to reassert his authority. In 1541, he had the Irish Parliament declare him king of Ireland and set about subduing the native population with a combination of fighting and negotiations. In the latter part of the sixteenth century, the Plantations policy was introduced, which encouraged English and Scottish protestants to settle in Ireland at the expense of the Catholic natives. The most successful of these plantations was Ulster, in northern Ireland. To make life more uncomfortable for the native Irish Catholic and dissentingHolding an opinion or belief that goes against official teaching or commonly held views.Holding an opinion or belief that goes against official teaching or commonly held views. populations, the PenalRelating to a punishment by law.Relating to a punishment by law. Laws were introduced in the seventeenth century. This disempowered Catholics and religious dissidents further, by denying them rights to hold land (above a certain value), positions in government and entry into the professions, as well as a higher education. A protestantSomeone following the western non-Catholic Christian belief systems inspired by the Protestant Reformation. minority was thus placed in all the main positions of power in Ireland, becoming richer and better educated, with the ability to direct Irish policy entirely to their own liking.

As time progressed, many Irish, both native and immigrant, grew tired of British control of Irish affairs and a growing movement for Irish independence developed. This came to a head in 1798 when the theories of the protestant Wolfe Tone and others like him – which pushed for an Ireland with all religions united in an effort to force the British out (preferably when they were distracted by a war elsewhere) – led to a brief and bloodily suppressed rebellion. This in turn led to the union with Britain to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland with effect from 1 January 1801. It wasn't just hopes of Catholic emancipation which – for a while at least – died with this union, It was eventually achieved in 1829 but the Irish parliament as well: Ireland was to be governed from London.

It was eventually achieved in 1829 but the Irish parliament as well: Ireland was to be governed from London.

Home Rule

It wasn't long before a home rule movement emerged, at first headed by the founder of the Irish Parliamentary Party, Charles Stuart Parnell. Parnell attracted a lot of negative attention, including letters published in The Times newspaper which purported to show his support of the Phoenix Park Murders of 1882. The letters were later proven to be a forgery, and Parnell emerged as something of a hero. He was less successful when it came to light that he was having a long-term affair with Katherine O'Shea, wife of a fellow Irish MP. The cuckoldedPast tense of 'cuckold', where a man is made a cuckold when his wife has an affair.Past tense of 'cuckold', where a man is made a cuckold when his wife has an affair. husband had put up with the relationship in the hope of inheriting a large sum of money from his wife's aunt. However, the wording of the will ruled out his ability to claim the inheritance, and so he eventually sued for divorce, naming Parnell in the process. The uproar led Gladstone to issue an ultimatumA final, uncompromising demand or set of terms, the rejection of which could lead to a severance of relations or to the use of force.A final, uncompromising demand or set of terms, the rejection of which could lead to a severance of relations or to the use of force.: Home Rule would not be supported by Gladstone unless Parnell stepped down, which Parnell refused to do. However, Parnell died in 1891, aged only 45, putting Home Rule back on the agenda. It sought a half-way point between complete independence, as espoused by the republicans, and complete British control of the province. The cause was taken up by several leading politicians, including Gladstone. Bills were introduced in 1886 and 1893, but failed to be passed in the CommonsPeople who weren't members of the clergy nor the nobility, or the House of Commons.People who weren't members of the clergyThe people ordained for religious duties, especially in the Christian Church. nor the nobilityThe highest hereditary stratum of the aristocracy, sitting immediately below the monarch in terms of blood and title; or the quality of being noble (virtuous, honourable, etc.) in character., or the House of Commons. and the Lords respectively. A Third Home Rule Bill was introduced in 1912, which failed to be passed by the Lords but was passed under the Parliament Act anyway, and received royal assent in 1914, but its implementation was postponed by the outbreak of the First World War.

Parnell attracted a lot of negative attention, including letters published in The Times newspaper which purported to show his support of the Phoenix Park Murders of 1882. The letters were later proven to be a forgery, and Parnell emerged as something of a hero. He was less successful when it came to light that he was having a long-term affair with Katherine O'Shea, wife of a fellow Irish MP. The cuckoldedPast tense of 'cuckold', where a man is made a cuckold when his wife has an affair.Past tense of 'cuckold', where a man is made a cuckold when his wife has an affair. husband had put up with the relationship in the hope of inheriting a large sum of money from his wife's aunt. However, the wording of the will ruled out his ability to claim the inheritance, and so he eventually sued for divorce, naming Parnell in the process. The uproar led Gladstone to issue an ultimatumA final, uncompromising demand or set of terms, the rejection of which could lead to a severance of relations or to the use of force.A final, uncompromising demand or set of terms, the rejection of which could lead to a severance of relations or to the use of force.: Home Rule would not be supported by Gladstone unless Parnell stepped down, which Parnell refused to do. However, Parnell died in 1891, aged only 45, putting Home Rule back on the agenda. It sought a half-way point between complete independence, as espoused by the republicans, and complete British control of the province. The cause was taken up by several leading politicians, including Gladstone. Bills were introduced in 1886 and 1893, but failed to be passed in the CommonsPeople who weren't members of the clergy nor the nobility, or the House of Commons.People who weren't members of the clergyThe people ordained for religious duties, especially in the Christian Church. nor the nobilityThe highest hereditary stratum of the aristocracy, sitting immediately below the monarch in terms of blood and title; or the quality of being noble (virtuous, honourable, etc.) in character., or the House of Commons. and the Lords respectively. A Third Home Rule Bill was introduced in 1912, which failed to be passed by the Lords but was passed under the Parliament Act anyway, and received royal assent in 1914, but its implementation was postponed by the outbreak of the First World War.

Home Rule was not universally popular in Ireland. Some nationalists foresaw in it an Ireland forever part of the United Kingdom, rather than its own, separate country. For Home Rule didn't provide complete autonomy, and represented devolution rather than true political independence. With London still responsible for issues such as taxation and defence, to the dedicated nationalists it offered 'mere crumbs from the rich man's political table.' Tim Pat Coogan, 1916: The Easter Rising, London: Orion (2001), p.31.

Tim Pat Coogan, 1916: The Easter Rising, London: Orion (2001), p.31.

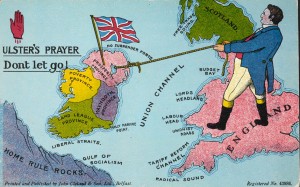

There was also opposition from the protestant minority based around Ulster, who had been most successful in the Plantations and their trade, economy, and culture were closely tied to England's. The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) was established to prevent, through force if necessary, the passage and implementation of Home Rule. Led by Edward Carson, a former crown prosecutor and a Unionist MP for Trinity College, Dublin it would use:

... all means which may be found necessary to defeat the present conspiracy to set up a Home Rule Parliament in Ireland. And in the event of such a parliament being forced upon us we further solemnly and mutually pledge ourselves to refuse to recognise its authority.The Ulster Covenant of 19 September 1912, quoted in Coogan, 1916, p.26

This was openly revolutionary yet many in Britain, including ToryBritish right-wing political faction based on the values of traditionalism and conservatism. Modern Conservatives are sometimes still referred to as Tories.British right-wing political faction based on the values of traditionalism and conservatism. Modern Conservatives are sometimes still referred to as Tories. MPs, Lord Rothschild, the Duke of Bedford, Edward Elgar, Rudyard Kipling, and the Conservative leader Bonar Law actively supported it. Furthermore, they ignored the group's illegal gunrunning activities and said nothing of the practice manoeuvres and parades done by the Force.

The Irish Volunteers

In late 1913, in retaliation for the growing UVF, the nationalist Irish Volunteers (IV) was established, with the academic Eoin MacNeill at its head. In theory, the Volunteers was an organisation ready to respond to protect Home Rule, but in practice members of the Irish RepublicanSomeone who believes power should belong to the people; someone who doesn't support a monarchy. Brotherhood (IRB) worked to take important positions and search for like-minded people. To them, the Volunteers was an instrument that could be used to form a republic.

During the first half of 1914, more than 150,000 people joined the IV. Their popularity caught the attention of the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, John Redmond, who insisted on putting his representatives on the board, threatening to start his own group if not. The leaders of the Volunteers reluctantly agreed, although it caused a divide within the leadership which was to have consequences later.

The accommodation with Redmond didn't last long: the IV split during the First World War after Redmond offered the Volunteers to the British government for service against Germany. Redmond's representatives were expelled and about 90 per cent of the Volunteers left to join his new National Volunteers. On the face of it, this should have been disastrous for the Irish Volunteers, but most officers and a large group from Dublin remained. Those 12,000 had the better experience and training, many shared a common goal, and were geographically well-placed to act when the time was right.

Plans, preparations and pitfalls

The Easter Rising was planned by the Military Council, the secretive body of IRB men operating within the Irish Volunteers. Based on the ideas of Wolfe Tone, they looked to England's enemies for help, both in distracting England and in providing them with resources. A Dublin uprising, it was hoped, would help to inspire the rest of the country to rise, with weapons, training and leadership provided by the Germans. These people would then march on Dublin, closing the trap laid for the British by those holding the centre of the city.

Germany had been approached in 1915 by former British diplomat Roger Casement and by Joseph Plunkett about the possibility of help in their rising, and this contact was maintained through proxiesPeople with the authority to represent someone else.People with the authority to represent someone else. in New York. It was agreed that a shipment of 20,000 rifles, 10 machine guns and 1,000,000 rounds of ammunition would be delivered to the Irish coast somewhere between 20 and 23 April by the Norwegian ship the Aud. The Germans had also agreed to allow an Irish prisoner of war volunteer brigade to form, so long as it only fought in defence of Ireland and not against Germany. These volunteers wouldn't be paid, but they would be equipped by the Germans. If Germany won the naval war, then they would send the brigade to Ireland, together with a supply of weapons. In addition, if the Rising were a success, then Germany would recognise Ireland as an independent state. However, most Irish PoWs refused to join, either out of their own consciences or because their relatives at home were still drawing their allowances. After the Aud had left port, further requests were issued by the Irish, including for staff officers to help with the uprising and for a German submarine to be sent to Dublin Harbour. The Council also requested that the arms arrive in Ireland on the evening of 23 April, after the rising had already started in Dublin. However, as well as it being impossible to work to such a narrow window in a war zone (and in enemy waters), the Aud was uncontactable. Unsurprisingly therefore, the Germans refused to fulfil these requests, but also neglected to tell the Council of their refusal. When the Aud thus approached the coast on 20 April, there was no welcoming party, as the Council had assumed the new date had been accepted. This, however, wasn't the only problem for the delivery: British intelligence had been aware of the arms shipment from a very early stage, having cracked the German communications with America. The Aud was cornered, whereupon its captain, Spindler, ordered his men into German naval uniforms, before taking to the lifeboats and scuttlingDeliberately sinking a ship.Deliberately sinking a ship. the ship. Casement, travelling separately on German U19, in the vain hope of preventing the rising due to the lack of German co-operation, was put in a collapsible dinghy and sent ashore, only to be captured early the next morning. Without the supply of arms, the nationwide rising was turned into one centred entirely on Dublin, destroying any chance of success.

The Germans had also agreed to allow an Irish prisoner of war volunteer brigade to form, so long as it only fought in defence of Ireland and not against Germany. These volunteers wouldn't be paid, but they would be equipped by the Germans. If Germany won the naval war, then they would send the brigade to Ireland, together with a supply of weapons. In addition, if the Rising were a success, then Germany would recognise Ireland as an independent state. However, most Irish PoWs refused to join, either out of their own consciences or because their relatives at home were still drawing their allowances. After the Aud had left port, further requests were issued by the Irish, including for staff officers to help with the uprising and for a German submarine to be sent to Dublin Harbour. The Council also requested that the arms arrive in Ireland on the evening of 23 April, after the rising had already started in Dublin. However, as well as it being impossible to work to such a narrow window in a war zone (and in enemy waters), the Aud was uncontactable. Unsurprisingly therefore, the Germans refused to fulfil these requests, but also neglected to tell the Council of their refusal. When the Aud thus approached the coast on 20 April, there was no welcoming party, as the Council had assumed the new date had been accepted. This, however, wasn't the only problem for the delivery: British intelligence had been aware of the arms shipment from a very early stage, having cracked the German communications with America. The Aud was cornered, whereupon its captain, Spindler, ordered his men into German naval uniforms, before taking to the lifeboats and scuttlingDeliberately sinking a ship.Deliberately sinking a ship. the ship. Casement, travelling separately on German U19, in the vain hope of preventing the rising due to the lack of German co-operation, was put in a collapsible dinghy and sent ashore, only to be captured early the next morning. Without the supply of arms, the nationwide rising was turned into one centred entirely on Dublin, destroying any chance of success.

The authorities, The Executive in Ireland was made up of three men: two politicians (a viceroyA ruler exercising authority in a colony on behalf of a sovereign.A ruler exercising authority in a colony on behalf of a sovereign. or lord lieutenant and a chief secretary) and one civil servantA government official - someone who works for the government.A government official - someone who works for the government. (the under-secretary). The viceroy was nominally the most senior of the three although the chief secretary, who was also a member of the Cabinet at Westminster, in reality had more power. These three were in charge of the police, army and civil service in Ireland. aware the Volunteers were being louder than usual, looked at several options for containing them. Sir Neville Chamberlain, who at that point was the Royal Irish Constabulary's (RIC) inspector-general, repeatedly warned the administration that the Volunteers were planning something and needed to be arrested. However, Ireland was a fine balancing act and no option looked favourable: it would be very easy to overstep the mark and ignite a revolution. At the time, it seemed better to let the situation lie. After all, the Volunteers didn't have enough men, training or weapons to pose a serious threat. This complacency cost all three of the Executive their jobs.

The Executive in Ireland was made up of three men: two politicians (a viceroyA ruler exercising authority in a colony on behalf of a sovereign.A ruler exercising authority in a colony on behalf of a sovereign. or lord lieutenant and a chief secretary) and one civil servantA government official - someone who works for the government.A government official - someone who works for the government. (the under-secretary). The viceroy was nominally the most senior of the three although the chief secretary, who was also a member of the Cabinet at Westminster, in reality had more power. These three were in charge of the police, army and civil service in Ireland. aware the Volunteers were being louder than usual, looked at several options for containing them. Sir Neville Chamberlain, who at that point was the Royal Irish Constabulary's (RIC) inspector-general, repeatedly warned the administration that the Volunteers were planning something and needed to be arrested. However, Ireland was a fine balancing act and no option looked favourable: it would be very easy to overstep the mark and ignite a revolution. At the time, it seemed better to let the situation lie. After all, the Volunteers didn't have enough men, training or weapons to pose a serious threat. This complacency cost all three of the Executive their jobs.

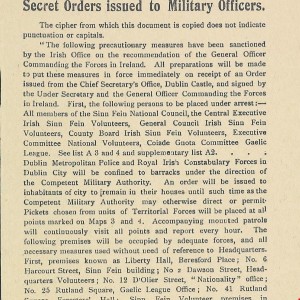

On 8 April 1916, Pearse announced a Volunteer training exercise in Dublin for Easter Sunday, 23 April. This provided a legitimate reason for armed republicans to be on the street and enabled the IRB members to continue to protect the secret of the rising from the rank and file. To prepare the way further, and to raise the idea of a military encounter in people's minds, a piece of deliberate misinformation known as the Castle Document was released by members of the Council. This document purported to be a British protocol to disarm the Irish, establish a military dictatorship and enforce conscription. There is still a considerable amount of debate over this document, with many claiming it was an actual British document, or that it was a British document made more dramatic by the IRB. Most historians, however, believe it to be a forgery. Apart from anything else, if it had been real then the capture of the Aud and Casement would have prompted its use.

There is still a considerable amount of debate over this document, with many claiming it was an actual British document, or that it was a British document made more dramatic by the IRB. Most historians, however, believe it to be a forgery. Apart from anything else, if it had been real then the capture of the Aud and Casement would have prompted its use.

The IRB, concerned about government moles and word getting out too soon, worked hard to keep the rising concealed from almost everyone within the Volunteers, including their chief of staff, MacNeill. The Fenian Rising of 1867 had been prevented when the authorities noticed an increase in the number of people going to confession. James Connolly, leader of the Irish Citizen Army, a small yet vocal organisation, was only brought into the conspiracy early in 1916 after the Military Council feared he would provoke an early revolution. The IRB benefitted from this alliance, buying both his silence and his military experience.

The Fenian Rising of 1867 had been prevented when the authorities noticed an increase in the number of people going to confession. James Connolly, leader of the Irish Citizen Army, a small yet vocal organisation, was only brought into the conspiracy early in 1916 after the Military Council feared he would provoke an early revolution. The IRB benefitted from this alliance, buying both his silence and his military experience.

When MacNeill eventually found out, just days before, he challenged the IRB members but Sean MacDermott, Castle Document in hand, talked him into believing there was no other option. The British would attack and the Irish would have to defend themselves. The Easter Rising, in these terms, was pre-emptive self-defence, and inescapable. MacNeill relented, believing there would be some hope of success with the shipment of German arms.

On Saturday 22 April, the day before the planned rising, MacNeill discovered he'd been duped again, and that the German arms supply had been stopped. In response MacNeill sent out countermands, driven across the country by The O'Rahilly, and went to the press immediately before the print deadline. In this way he addressed the rank and file without using the command structures put in place by the IRB. The Sunday Independent published in print and headline placards across the city MacNeill's order:

Owing to the very critical situation, all orders given to the Irish Volunteers for tomorrow, Easter Sunday, are hereby rescinded and no parades, marches or other movements of Irish Volunteers will take place. Each individual Volunteer will obey this order strictly in every particular.Quoted in Michaeil T. Foy & Brian Barton, The Easter Rising, Stroud: The History Press (2011) p.62

The Council, dispersed in safe houses across the city in preparation for the following day, did not have chance to react. Instead they met on the morning of Easter Sunday to discuss options. With MacNeill having prevented the Rising on Easter Sunday, the Military Council postponed it until the following day, Easter Monday. Too much time and effort had been put into the planning, and the Council believed they would never have as good an opportunity again. But they put on a show of standing down and MacNeill was comforted: he had been assured there would be no rising on Easter Sunday and believed the wind had been taken out of the Council's sails.

The Rising

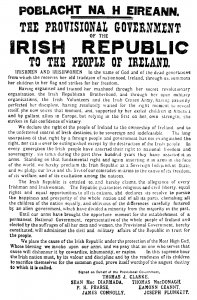

On Easter Monday just before noon, James Connolly and Patrick Pearse led their battalionA military unit, typically consisting of between 300 and 800 soldiers.A military unit, typically consisting of between 300 and 800 soldiers. of Volunteers, Citizen Army, and Fianna (a military, nationalistic boy scout movement) from Liberty Hall Liberty Hall was the home of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union, and thus also the base of the Citizen Army, which had been established to defend strikers from police in the 1913 Dublin lockout to the General Post Office (GPO), which would serve as their military headquarters. It was seized and a number of off-duty soldiers were taken prisoner. The Tricolour flag was raised and at 12:45, Pearse, who had been chosen as the new president,

Liberty Hall was the home of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union, and thus also the base of the Citizen Army, which had been established to defend strikers from police in the 1913 Dublin lockout to the General Post Office (GPO), which would serve as their military headquarters. It was seized and a number of off-duty soldiers were taken prisoner. The Tricolour flag was raised and at 12:45, Pearse, who had been chosen as the new president, Connolly was named vice-president and the commandant-general of the Dublin division, which effectively put him in charge of all fighting in Dublin. went outside to read their proclamationA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importance and declare the establishment of a provisional government.

Connolly was named vice-president and the commandant-general of the Dublin division, which effectively put him in charge of all fighting in Dublin. went outside to read their proclamationA public or official announcement dealing with a matter of great importance and declare the establishment of a provisional government. There were seven signatories to the proclamation, all of whom were later executed. These were: Tom Clarke, Sean MacDermott, Thomas MacDonagh, Patrick Pearse, Eamonn Ceannt, James Connolly, and Joseph Plunkett. The reception from the milling crowd was lukewarm, greeted by a few cheers, some disbelief and considerable indifference. Copies were posted around the city and sent to other garrisons. A few onlookers bought one as a souvenir, rightly suspecting it would be worth more in the months that followed. The Provisional Government also managed to transmit the proclamation to parts of Europe and to America, although, as they couldn't get the receiver working, they didn't know if the message had been received.

There were seven signatories to the proclamation, all of whom were later executed. These were: Tom Clarke, Sean MacDermott, Thomas MacDonagh, Patrick Pearse, Eamonn Ceannt, James Connolly, and Joseph Plunkett. The reception from the milling crowd was lukewarm, greeted by a few cheers, some disbelief and considerable indifference. Copies were posted around the city and sent to other garrisons. A few onlookers bought one as a souvenir, rightly suspecting it would be worth more in the months that followed. The Provisional Government also managed to transmit the proclamation to parts of Europe and to America, although, as they couldn't get the receiver working, they didn't know if the message had been received.

Both supporters and opponents came to the GPO early in the week, either to demand a surrender or to offer to fight, including a Finn and a Swede who asked for – and were granted – the right to fight England (which was an allyA state (or person) that is formally working with another state (or person), usually confirmed by a treaty or other official agreement.A state (or person) that is formally working with another state (or person), usually confirmed by a treaty or other official agreement. of their own foe, Russia). Fighting started in earnest on Wednesday and continued and intensified into Thursday, when Connolly was shot in the leg, shattering two inches of shin bone and removing him from the action. This was the second time he'd been shot, but the first time was just a graze on the arm which Connolly managed to get treated in secret. The rebels had expected the Rising to be fought mainly with guns and hand-to-hand fighting, and hadn't planned for anything heavier, with particularly the socialist Connolly believing damage to property would dissuade the British from the use of artilleryLarge guns used in warfare, or referring to the group that uses those guns.Large guns used in warfare, or referring to the group that uses those guns.. They therefore dug in, immediately limiting their options and providing the British with easy targets. They guessed wrong: on Thursday, heavy artillery and incendiary bombs dropped, starting a fire that raged down the opposite side of O'Connell Street (which was then Sackville Street) which lit up Dublin. Dublin Fire Brigade's chief officer, Captain Purcell, estimated that 179 buildings were set ablaze during the week, with financial losses of £1 million worth of property and £750,000 of stock destroyed in O'Connell Street alone.

This was the second time he'd been shot, but the first time was just a graze on the arm which Connolly managed to get treated in secret. The rebels had expected the Rising to be fought mainly with guns and hand-to-hand fighting, and hadn't planned for anything heavier, with particularly the socialist Connolly believing damage to property would dissuade the British from the use of artilleryLarge guns used in warfare, or referring to the group that uses those guns.Large guns used in warfare, or referring to the group that uses those guns.. They therefore dug in, immediately limiting their options and providing the British with easy targets. They guessed wrong: on Thursday, heavy artillery and incendiary bombs dropped, starting a fire that raged down the opposite side of O'Connell Street (which was then Sackville Street) which lit up Dublin. Dublin Fire Brigade's chief officer, Captain Purcell, estimated that 179 buildings were set ablaze during the week, with financial losses of £1 million worth of property and £750,000 of stock destroyed in O'Connell Street alone.

The pounding continued on Friday, with the GPO itself hit. Once the roof started to fall in, evacuation procedures (first of the women) began. Initially the plan was to evacuate to Williams & Woods jam factory, which had already been taken by the British, and The O'Rahilly died leading men to regain it. He had originally been a supporter of MacNeill, and had almost come to blows with Pearse – whom he called a poet and idealist – when the plan had been exposed. However, once he found out the Rising was happening anyway, he felt it only honourable to join in, and he brought with him a supply of arms. The 'The' comes from an old Gaelic designation for the chief of a clan. Connolly was too injured to continue leading, so MacDermott nominated, and Connolly ratified, the 18-year-old Fianna scout Sean McLoughlin as commandant, responsible for getting the garrison to safety. McLoughlin hatched an escape plan, but it meant leaving all the wounded – save Connolly – behind. Concerns were expressed by Connolly and most other members of the Provisional Government not just about treatment of the wounded, but over the risks people would have to take to fulfil the plan. Furthermore, scores of civilians, including women and children, were being shot and killed. Thus, the Provisional Government surrendered on Saturday 29 April. The surrender document read:

He had originally been a supporter of MacNeill, and had almost come to blows with Pearse – whom he called a poet and idealist – when the plan had been exposed. However, once he found out the Rising was happening anyway, he felt it only honourable to join in, and he brought with him a supply of arms. The 'The' comes from an old Gaelic designation for the chief of a clan. Connolly was too injured to continue leading, so MacDermott nominated, and Connolly ratified, the 18-year-old Fianna scout Sean McLoughlin as commandant, responsible for getting the garrison to safety. McLoughlin hatched an escape plan, but it meant leaving all the wounded – save Connolly – behind. Concerns were expressed by Connolly and most other members of the Provisional Government not just about treatment of the wounded, but over the risks people would have to take to fulfil the plan. Furthermore, scores of civilians, including women and children, were being shot and killed. Thus, the Provisional Government surrendered on Saturday 29 April. The surrender document read:

In order to prevent the further slaughter of Dublin citizens, and in the hope of saving the lives of our followers now surrounded and hopelessly outnumbered, the members of the Provisional Government at Headquarters have agreed to unconditional surrender, and the Commandants of the various districts in the City and Country will order their commands to lay down arms.

Pearse and Connolly both signed it.

Fighting had not been limited to the GPO. On Easter Monday, other groups had made their way to their targets, including St Stephen's Green, Jacob's biscuit factory, the South Dublin Union (which contained a number of destitute, ill, and mentally unstable Dubliners) Boland's bakery and mill, the Four Courts and the Mendicity Institution. Others went to guard approaches to the city or train stations in an attempt to stop reinforcements from entering.

Each target had been chosen beforehand as strategically important, but some choices showed bad planning. One such miscalculation was the inability or unwillingness of Sean Connolly's battalion to take Dublin Castle. There is no evidence to suggest that the Castle was a premeditated target, although Sean Connolly shot an unarmed policeman guarding the Castle on the way to City Hall and made some small attempt to capture it. The policeman was the first victim of the uprising. Coogan argues it was not targeted as the rebels had no idea how few soldiers were in it, and didn't want to waste ammunition and men on a heavily fortified target. Little did they know that most of the garrison were away at the races The Irish Grand National was being held at Fairyhouse Racecourse and the Castle was largely undefended. In ignoring it, they missed a vital opportunity both to fortify their movement and to strike a sizeable propaganda blow. There were a number of other missed opportunities, such as the failure to take the Shelbourne Hotel by St Stephen's Green,

The Irish Grand National was being held at Fairyhouse Racecourse and the Castle was largely undefended. In ignoring it, they missed a vital opportunity both to fortify their movement and to strike a sizeable propaganda blow. There were a number of other missed opportunities, such as the failure to take the Shelbourne Hotel by St Stephen's Green, The rebels chose to take the exposed Green rather than the hotel and were forced to retreat to the College of Surgeons once the British army took the hotel. and the Crown Alley Telephone Exchange.

The rebels chose to take the exposed Green rather than the hotel and were forced to retreat to the College of Surgeons once the British army took the hotel. and the Crown Alley Telephone Exchange. A group were on their way to take it when they were warned off by someone they considered a supporter of the movement, who said it was full of soldiers. Thus, they gave up only for the British to occupy an empty exchange five hours later. Jacob's factory was another mistake: it was not of any value to the British and too well defended for a frontal attack, so the British played a long game, keeping the defenders sleep deprived and occasionally sniping at them. The defenders got worn down, with very little contact with the outside world and very little fighting, and very little but biscuits to eat.

A group were on their way to take it when they were warned off by someone they considered a supporter of the movement, who said it was full of soldiers. Thus, they gave up only for the British to occupy an empty exchange five hours later. Jacob's factory was another mistake: it was not of any value to the British and too well defended for a frontal attack, so the British played a long game, keeping the defenders sleep deprived and occasionally sniping at them. The defenders got worn down, with very little contact with the outside world and very little fighting, and very little but biscuits to eat.

Partially, the missed opportunities were caused by the chaos and confusion surrounding the Rising. Many Volunteers obeyed the orders of their chief of staff and didn't turn out. Others were not at home when the call came in on Monday morning, or thought it was merely for exercises, and so either didn't turn out or came late. In total only between 1,000 and 1,500 answered the call. With manpower so thinly spread, the rebels couldn't hope to occupy successfully all the important places. It has been estimated that at least 800 men were needed to secure the Boland's mills area, yet they had only 173 at their disposal. Within the area stood the British army's Beggar's Bush Barracks, the approach to which saw some of the most intense fighting of the Rising in the Battle of Mount Street Bridge. On Wednesday 26 April, British reinforcement Sherwood Foresters arrived in Dublin and sought to reach the Barracks, but were easy targets for those in hiding along the route. Eventually they did manage to take the Volunteer positions, but at a cost: five Volunteers were dead, but the British had lost four officers with another fourteen wounded and two hundred and sixteen men of other ranks killed or wounded. Those who survived withdrew to the mill, where the whole battalion held out until the surrender.

On Wednesday 26 April, British reinforcement Sherwood Foresters arrived in Dublin and sought to reach the Barracks, but were easy targets for those in hiding along the route. Eventually they did manage to take the Volunteer positions, but at a cost: five Volunteers were dead, but the British had lost four officers with another fourteen wounded and two hundred and sixteen men of other ranks killed or wounded. Those who survived withdrew to the mill, where the whole battalion held out until the surrender.

With so few Volunteers stretched across wide areas of the city, there weren't the proper resources to allow them to sleep, and fatigue became a serious issue. Commandants such as Pearse didn't sleep at all – despite sleeping draughts – which affected their judgement and mental and emotional states, as well as putting them under severe physical strain: one captain, Fred Fahy, even experienced a heart attack. Many on both sides were wounded in friendly fireWeapon fire coming from one's own side which causes injury or death.Weapon fire coming from one's own side which causes injury or death. or in accidents of their own making, and one group of reinforcements sent along O'Connell Street ended up getting into a gunfight with the defenders they were meant to be helping.

A significant number of Volunteers were young, as were several of their officers: at the Mendicity Institution all Volunteers bar one were 25 or younger, and the commander, Sean Heuston, was also 25. Some were actually Fianna scouts who were generally used as runners but were sometimes involved in combat. Often commanders did what they could to keep children out of harm's way: de Valera sent all but one of those under 18 at Boland's away on Tuesday morning. But many were not happy being treated as children, and joined the action elsewhere, as happened with a group on Easter Monday, who simply joined the garrison at the GPO.

It wasn't just the Irish who were ill-prepared: the British army was not ready for the attack and taken completely by surprise. There were so few troops in Ireland Two thousand four hundred in total – excluding administrative staff – across nine barracks in Dublin and the rest of Ireland, with only four hundred immediately available to respond. that their initial response was slow and poor. Many local troops operated in scratch units, hastily put together when men couldn't reach their own units, and were working under commanders they had never met before. Plus, they received little help from the unarmed police officers who, by 3pm on Easter Monday, were pulled off the streets after suffering two fatalities. However, even by later that day, more troops were entering the city, and by the early evening, an extra 1,600 troops were available, even if they were somewhat confused. When troops arrived from England, many were ill-equipped and surprised to be landing in Ireland, while others assumed they had landed on the Continent and started speaking French to the locals. Furthermore, most were young and inexperienced, with only three months basic training under their belts. Three quarters of the British soldiers at Mount Street Bridge had less than three months' service and lacked any training in urban fighting. Their situation was not helped by those in command who were eager to crush the rebellion quickly, and so forced sometimes bad decisions on those on the ground.

Two thousand four hundred in total – excluding administrative staff – across nine barracks in Dublin and the rest of Ireland, with only four hundred immediately available to respond. that their initial response was slow and poor. Many local troops operated in scratch units, hastily put together when men couldn't reach their own units, and were working under commanders they had never met before. Plus, they received little help from the unarmed police officers who, by 3pm on Easter Monday, were pulled off the streets after suffering two fatalities. However, even by later that day, more troops were entering the city, and by the early evening, an extra 1,600 troops were available, even if they were somewhat confused. When troops arrived from England, many were ill-equipped and surprised to be landing in Ireland, while others assumed they had landed on the Continent and started speaking French to the locals. Furthermore, most were young and inexperienced, with only three months basic training under their belts. Three quarters of the British soldiers at Mount Street Bridge had less than three months' service and lacked any training in urban fighting. Their situation was not helped by those in command who were eager to crush the rebellion quickly, and so forced sometimes bad decisions on those on the ground. Such as at Mount Street Bridge, where there were other undefended ways into the city, but High Command insisted on them using that route. Even those who had experience in the trenchesLong, narrow ditchesLong, narrow ditches were not necessarily prepared for urban fighting, with significant female and child casualties. British Lieutenant Jameson recorded that 'Everybody who had been in France seemed to think the Dublin fighting was a far worse thing to be in!'

Such as at Mount Street Bridge, where there were other undefended ways into the city, but High Command insisted on them using that route. Even those who had experience in the trenchesLong, narrow ditchesLong, narrow ditches were not necessarily prepared for urban fighting, with significant female and child casualties. British Lieutenant Jameson recorded that 'Everybody who had been in France seemed to think the Dublin fighting was a far worse thing to be in!' Jameson Letters, quoted in Foy & Barton, Easter Rising, p.221

Jameson Letters, quoted in Foy & Barton, Easter Rising, p.221

The situation was not clear cut: brothers could be fighting with each other or against them. Some families had children fighting both for the Rising and in Dublin for the British Army, having joined up for the war in France. A number of Irish men were killed fighting for the British, and this did little to increase the public's support for the Rising.

Civilians added to the chaos: even on Tuesday morning, they still tried to go to work or drive through the streets, only to be scared off by Volunteers. Some made use of the confusion across the city to loot abandoned shops. Volunteers and British soldiers made attempts to discourage the looters by firing over their heads, but any discouragement didn't last for long, and soon the looters – or a different set of looters – would be back.

A large number of civilians were wounded or killed during the Rising, either by being caught in the cross-fire or mistaken for a Volunteer or a 'TommyA British private soldier.A British private soldier.'. Sometimes it was just the intensity of the moment that led inexperienced soldiers to fire before assessing the situation. Other civilians were killed because they failed to respond quickly enough – one old lady was killed by British soldiers because she was deaf and hadn't heard their commands to halt. Many sources also bear witness to the number of curious bystanders the fighting attracted. One volunteer, Dick Humphries, who was fighting at the GPO was amazed by the onlookers at O'Connell Bridge: 'Indeed, one would think from their appearance that the whole thing was merely a sham battle got up for their amusement.' (Humphries, GPO Diary, quoted in Foy & Barton, Easter Rising, p.243) A number of St John's Ambulance volunteers and Red Cross workers, who tried to help all injured people, were also caught in the cross-fire.

Many sources also bear witness to the number of curious bystanders the fighting attracted. One volunteer, Dick Humphries, who was fighting at the GPO was amazed by the onlookers at O'Connell Bridge: 'Indeed, one would think from their appearance that the whole thing was merely a sham battle got up for their amusement.' (Humphries, GPO Diary, quoted in Foy & Barton, Easter Rising, p.243) A number of St John's Ambulance volunteers and Red Cross workers, who tried to help all injured people, were also caught in the cross-fire.

There were other times when it seemed civilians – or unarmed prisoners – were shot out of cruelty. An inquest was held after one particularly notorious incident in North King Street, when 13 men died under suspicious circumstances on Saturday and Sunday 29 and 30 April, in their houses and after battle had finished. This inquest led to one of the largest identity parades in history, when 2,000 men of the Staffordshire Regiment were lined up before the female witnesses. Unsurprisingly, they couldn't identify those responsible, and the inquest did not find the culprits. In May 1916, Sir Edward Troup, permanent secretary at the Home Office blamed an order given by Brigadier-General William Lowe, who had overall command of military operations at the time. It was suggested that:

The root of the mischief was the military order to take no prisoners. This in itself may have been justifiable – but it should have been made clear that it did not mean that an unarmed rebel might be shot after he had been taken prisoner. Still less could it mean that a person taken on mere suspicion could be shot without trial.Quoted in Coogan, 1916, p.156

Other notorious shootings included summary executions of two journalists and a local eccentric character, pacifistA person who believes that war and violence are unjustifiable, or the belief that war and violence cannot be justified.A person who believes that war and violence are unjustifiable, or the belief that war and violence cannot be justified. and activist called Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, ordered by Captain Bowen-Colthurst. This act only came to light by the efforts of another British officer, Major Sir Francis Vane, who had his career ruined as a result. Once the evidence was there and acknowledged, the establishment had to act against Bowen-Colthurst, although he was convicted by court martialRelating to fighting or war.Relating to fighting or war. – for a civilian crime – rather than in a civilian court. This kept the details out of the public eye, and thus covered up the illegal actions of some in the army.

Attacks on civilians weren't limited to the British army. In creating barricades along St Stephen's Green, rebels shot a number of civilians for refusing to donate their vehicles or for otherwise not showing enough support. Nor was their choice of the South Dublin Union as a stronghold particularly ethical: in using the largest poorhouse, infirmary and asylum in the city the rebels were guaranteeing that innocents would be caught in the middle of the fighting.

Civilian approval or disapproval of the Rising remains a hotly debated subject. Undoubtedly there were some in Dublin – such as the separation women whose husbands were fighting on the frontline, or those whose livelihoods depended on the British or the military – who did not approve. There was also considerable concern about the risks the Rising presented to those living in Dublin. The public often made their feelings very clear to the rebels: those stationed around Jacob's factory suffered physical and verbal abuse from the locals to such an extent that they had to withdraw. But there were also shows of support for the rebels, particularly in some districts, and Foy and Barton suggest that some who didn't show support were either too scared or thought it senseless to do so once with the military were firmly in control.

Major-General Sir John Maxwell arrived in Ireland on Friday with the specific task of ending the Rising quickly. Maxwell seemed like a good choice for the job, having no prior connection with Ireland, having experience of political situations in war, and also being fit and available for duty. Although his reputation was slightly tarnished by his involvement in the Gallipoli campaign. However, time spent in Africa had made him convinced of the need to keep Britain and her empire united, and he insisted on unconditional surrender of the rebel forces. This hard-line stance was partly a result of the British belief of considerable German involvement in the Rising.

Although his reputation was slightly tarnished by his involvement in the Gallipoli campaign. However, time spent in Africa had made him convinced of the need to keep Britain and her empire united, and he insisted on unconditional surrender of the rebel forces. This hard-line stance was partly a result of the British belief of considerable German involvement in the Rising. The Rising coincided with a heavy gas attack on the Dublin Fusiliers on the Western Front, which wiped them out. Germans also put a placard along the front line in sight of Irish soldiers stating 'Irishmen, heavy uproar in Ireland. English guns are firing at your wives and children.' (quoted in Foy and Barton, Easter Rising, p.287). With Ireland technically being part of the United Kingdom – whatever the wishes of the rebels – seeking help from the enemy, against whom thousands of British were fighting and dying each week, was seen as a gross act of treason.

The Rising coincided with a heavy gas attack on the Dublin Fusiliers on the Western Front, which wiped them out. Germans also put a placard along the front line in sight of Irish soldiers stating 'Irishmen, heavy uproar in Ireland. English guns are firing at your wives and children.' (quoted in Foy and Barton, Easter Rising, p.287). With Ireland technically being part of the United Kingdom – whatever the wishes of the rebels – seeking help from the enemy, against whom thousands of British were fighting and dying each week, was seen as a gross act of treason.

Thanks to MacNeill's countermand and the failure of the arms drop, almost all of the fighting was contained in Dublin. There were, however, a few exceptions, including the battalion led by Thomas Ashe and Richard Mulcahy, who disarmed a number of police barracks in the Fingal area, and participated in a five-and-a-half-hour shoot out with the RIC in Ashbourne, which they won. This made Ashe something of a legend although Foy and Barton argue that it was actually his deputy who rescued the situation many times, and it was he who deserved the praise. In Wexford, there was a short-lived and bloodless occupation of Enniscorthy.

Different figures exist for the total numbers involved in the Rising, as well as those killed and injured. There were between 1,000 and 1,500 insurgents, out of whom about 60 were killed in action. Combined figures for Volunteers and civilians show 318 dead and 2217 wounded, of which about 256 were civilians. Over one hundred British and Irish soldiers were killed, around three hundred and fifty injured and nine missing. Sixteen police were killed and a further twenty-nine were injured.

The Aftermath

Once the unconditional surrender had been given, and the battalions outside the GPO had been convinced of its necessity, the rebels were rounded up and taken to the Rotunda, where they spent an uncomfortable night out in the open, before being marched to Richmond Barracks. On the march there, they were greeted with open hostility from the watching crowds, adding further to their despondency. There, the 'main' conspirators were separated from the rest and taken to Kilmainham Gaol, in order to face courts martial. The British government also made the most of the opportunity to round up nationalists, including Sinn Feiners, who hadn’t had anything to do with the Rising: the total number of those arrested was 3,430 men and 79 women, more than double the number of participants.

The British government also made the most of the opportunity to round up nationalists, including Sinn Feiners, who hadn’t had anything to do with the Rising: the total number of those arrested was 3,430 men and 79 women, more than double the number of participants.

'The whole court martial process was deeply flawed. It was established and implemented in considerable haste: three or four men would be tried together in a remarkably short time, the evidence given and the intelligence material cited was frequently circumstantial, misleading and sometimes completely inaccurate.' Foy & Barton, Easter Rising, pp.296-7 Of the one hundred and eighty-six men and one woman tried, eleven were acquitted.

Foy & Barton, Easter Rising, pp.296-7 Of the one hundred and eighty-six men and one woman tried, eleven were acquitted. The one female was Countess Markievicz, who took an active military role at St Stephen's Green. She was found guilty and sentenced to death, which was commuted to life in prison on the orders of Asquith. In 1918, she became the first woman elected to the House of Commons, although she never took her seat. Of the 176 convicted 88 were given sentences of death by firing squad. In the end, 15 were eventually killed by firing squad before pressure from Asquith and the government in Britain put a halt to the executions. Seventy-three had their sentences commuted to penalRelating to a punishment by law. servitude ranging from three years to life. Casement, who was tried by the High Court of Justice in London was also found guilty and was executed by hanging on 3 August 1916.

The one female was Countess Markievicz, who took an active military role at St Stephen's Green. She was found guilty and sentenced to death, which was commuted to life in prison on the orders of Asquith. In 1918, she became the first woman elected to the House of Commons, although she never took her seat. Of the 176 convicted 88 were given sentences of death by firing squad. In the end, 15 were eventually killed by firing squad before pressure from Asquith and the government in Britain put a halt to the executions. Seventy-three had their sentences commuted to penalRelating to a punishment by law. servitude ranging from three years to life. Casement, who was tried by the High Court of Justice in London was also found guilty and was executed by hanging on 3 August 1916. He was tried under a statute from 1351, written in Norman French, that defined treason as 'levying war against the king, or being adherent to the king's enemies in his realm, giving them aid and comfort in the realm or elsewhere' (Andrew Lycett, 'The Irish Volunteer', History Today, 66 (2016). The argument was over whether or not there was a third comma: if there was, then all three aspects of the definition could be interpreted as treasonous whether taking place in the realm or elsewhere; if there wasn't, then it was a qualification of the two main offences. Casement was thus 'hanged on a comma'. It has also been argued that his diaries, which detailed homosexual affairs, were used to colour opinion against him at home and abroad and, ultimately, led to his execution. De Valera was the only commandant not to have a death sentence carried out

He was tried under a statute from 1351, written in Norman French, that defined treason as 'levying war against the king, or being adherent to the king's enemies in his realm, giving them aid and comfort in the realm or elsewhere' (Andrew Lycett, 'The Irish Volunteer', History Today, 66 (2016). The argument was over whether or not there was a third comma: if there was, then all three aspects of the definition could be interpreted as treasonous whether taking place in the realm or elsewhere; if there wasn't, then it was a qualification of the two main offences. Casement was thus 'hanged on a comma'. It has also been argued that his diaries, which detailed homosexual affairs, were used to colour opinion against him at home and abroad and, ultimately, led to his execution. De Valera was the only commandant not to have a death sentence carried out His sentence was due to be carried out after Connolly's but was commuted to life imprisonment thanks to the intervention of Asquith. and he later became the president of Ireland.

His sentence was due to be carried out after Connolly's but was commuted to life imprisonment thanks to the intervention of Asquith. and he later became the president of Ireland.

Although many in Ireland did not support the initial rising, the punishment of the rebels and others was thought of as too harsh, and those involved now started to be seen as martyrs to the cause. Sympathy also increased due to the unwillingness of the establishment to undertake the courts martial in public. With the exception of MacNeill, all were held in secret, and the proceedings of the courts were not released. This, as those involved admitted, was at least in part due to the very flimsy evidence on which many were convicted and executed. By September 1916, Chief Secretary Duke thought that three-quarters of the population disapproved of the British reaction and were becoming more sympathetic to the cause. As George Bernard Shaw wrote, 'My own view is that the men who were shot in cold blood, after their capture or surrender, were prisoners of war, and that it was therefore, entirely incorrect to slaughter them…It is absolutely impossible to slaughter a man in this position without making him a martyr and a hero…'

A Blood sacrifice?

There is an argument that the leaders of the Rising never expected to win against the British, but that they deliberately martyred themselves to give impetusThe force or energy with which a body moves; or something that makes a process or activity happen or happen more quickly.The force or energy with which a body moves; or something that makes a process or activity happen or happen more quickly. to the nationalist movement as a whole. This, it is argued, is why they chose Easter as the time for the Rising, as its religious significance fit so well with the aims of the group.

Certainly with hindsight the Rising seemed suicidal, particularly after the failure of the arms delivery, and MacNeill's countermand. Still popular at the time, thanks to First World War poets such as Rupert Brooke, was the notion that a cause or ideal required a sacrifice of blood for it to succeed. There is no doubt that many of the leaders were idealists, nor that they were unaware of such sentiments. Awaiting his execution on 11 May 1916, MacDermott wrote 'we die that the Irish nation may live. Our blood will re-baptise and reinvigorate the old land. Knowing this it is superfluous to say how happy I feel.' Piaras MacLochlainn, Last Words: Letters and statements of the leaders executed after the Rising at Easter, 1916, Dublin: Kilmainham Jail Restoration Society (1971) p.171 However, Foy and Barton argue that the leaders believed victory really was possible, or that they expected to die in battle, which could prevent them from becoming martyrs.

Piaras MacLochlainn, Last Words: Letters and statements of the leaders executed after the Rising at Easter, 1916, Dublin: Kilmainham Jail Restoration Society (1971) p.171 However, Foy and Barton argue that the leaders believed victory really was possible, or that they expected to die in battle, which could prevent them from becoming martyrs.

In the short term, the Easter Rising was without doubt a complete failure. At best, it was strategically flawed, reliant on outside help, confused and lacking in basic resources. However, it is not possible to doubt its ultimate success. The aim was to create an independent Irish republic and, in 1922, the Irish Free State was founded. Granted, that is not where the troubles ended, and the many divisions in Ireland are still in evidence now. Yet Ireland as we know it today would not exist without the Easter Rising. 'The Rising drove Home Rule off the stage, created a climate of opinion in which the guerrilla war against British troops and Black and Tans could be waged, and led, through civil war and much bloodshed and destruction, to the establishment of the Republic. Pearse won.' A.P. Ryan, ‘The Easter Rising, 1916’, History Today 16 (1966)

A.P. Ryan, ‘The Easter Rising, 1916’, History Today 16 (1966)

Things to think about

- How much popular support was there for a Rising?

- Would the Rising have succeeded without MacNeill’s countermand?

- Were the leaders of the Rising just deluded idealists, or was there a chance they could succeed?

- Did the leaders willingly sacrifice themselves to promote the cause: was there an intentional blood sacrifice?

- Where does responsibility lie for the Rising, and was the British government at fault for unrest in Ireland?

- What would have happened to Ireland without the Rising?

- How is it best to remember and study the Rising?

- What lessons can be learned from the Rising, and how are they applicable to Ireland today?

- What were the levels of popular support for the Rising, and how and why did they change?

- How did Britain’s involvement in the First World War affect the Rising?

Things to do

- The internet is a fantastic resource for primary sources on the Easter Rising, and offers a great opportunity for delving into the digital archives. The best places to start are the National Archives and EuroDocs.

- Dublin is always worth a visit. In the centenary year of the Easter Rising, a number of places are showing special exhibitions, including Dublin Castle and Kilmainham Gaol.

Further reading

As we are in the centenary year of the Rising, a huge number of books have been published on the subject, many of which are very good. They have been helped by the recent release of British papers, which detail the British side and the courts martial carried out. Michael T. Foy and Brian Barton's The Easter Rising (The History Press, 2011), while sometimes hard-going and a bit repetitive, is one of the best researched and most thorough books on the Rising in print. Fearghal McGarry's Rebels: Voices from the Easter Rising (Penguin Ireland, 2011) makes good use of the thousands of witness statements, giving a good overview of many individual's stories, thoughts and emotions on the Rising.

- Log in to post comments